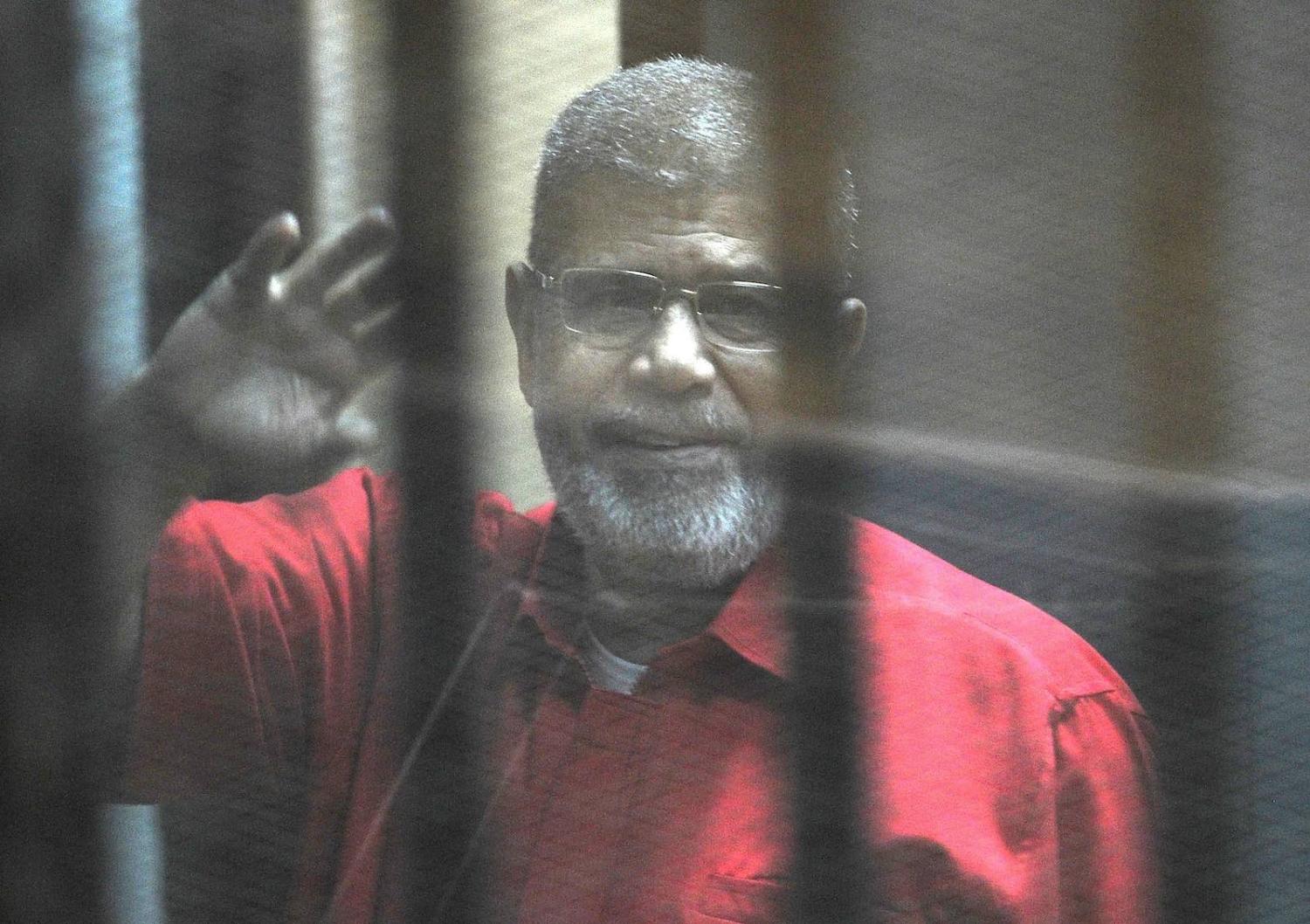

The death of former Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi in Cairo on 17 June provides an opportunity to reflect on both the certainties and the vagaries of Egyptian politics.

The fact that he was an elected leader who was removed, albeit to widespread popular relief, by the Egyptian military in 2013 dominates Western perceptions of his place in modern Egyptian history. The decimation of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt which followed his removal attracted a modest level of external attention. The abuses against all sources of dissent that accompanied the consolidation in power of another elected leader, Abdel Fatah el-Sisi, raised awkward questions for a year or two about the extent to which concerns for the respect of human rights should shape Western foreign policy approaches. But the immediacy of those issues has faded with the passage of time.

For most of my Egyptian friends, Morsi and the brief flirtation with the Brotherhood in government is something of an embarrassment.

For most of my Egyptian friends, Morsi and the brief flirtation with the Brotherhood in government is something of an embarrassment. For many, it is not for discussion lest it raise questions about one’s attitudes to contemporary politics. For others, it is merely an aberration or moment of misguided enthusiasm for change best expunged from popular memory.

For outsiders, the gap between the liberal political values espoused by many Egyptian interlocutors at the height of the 2001 uprising and their insouciance at, or emphatic endorsement of the violence of the retribution which followed, says a great deal about the moral quandaries of contemporary Egypt. But few Egyptians concern themselves with such issues.

So much for the vagaries of human fortune, political or otherwise.

But the Morsi experience also underscored some of the certainties of Egypt. Three of these bears mentioning.

First and foremost, it was a reminder that the military in Egypt will not tolerate challenges to its sense of national identity and the values which underpin the stability of the system over which it exercises ultimate authority.

The military was instrumental in removing Hosni Mubarak because the corruption and nepotism of his rule had become sufficiently dysfunctional, and had shown sufficient signs of becoming worse, that systemic instability loomed. With demonstrations continuing in Tahrir Square and Mubarak convinced of his legitimacy in office and rejecting earnest advice from his former military colleagues to step aside, corrective action was required. The military, uniquely, were prepared to take it.

In a similar vein, until he fell, Morsi continued to rely on his electoral victory credentials to seek political solutions where in reality none remained open to him. He was blind to the fact that the same fundamental drivers for the military that led them to remove Mubarak would see them willing to do the same to him, when the time came.

Another certainty is that civilian politics in Egypt remains poorly-equipped to succeed in meeting the challenges of government against the backdrop of military power, and the determination of the underlying and institutional features of the Egyptian state apparatus to protect and pursue their particular interests and prerogatives.

The young, mostly secular activists who began the Egyptian uprising in 2011 were no match for the political sophistication and mobilising capability of the Brotherhood when it decided to join them in their efforts. But on arrival in government the Brotherhood also proved incapable of building coalitions with other actors capable of creating and delivering programs that made a positive difference to the lives of ordinary Egyptians.

Disillusion with the Brotherhood grew, societal divisions widened dramatically, shortages of fuel impacted ordinary citizens and the security situation deteriorated to a point where the military were welcome to return as the arbiters of Egypt's political destiny.

The gross abuses of human rights that followed were attributable not only to the intent of the military to destroy the Brotherhood as both an organisation and as an alternative, Islamist vision for Egypt. They also arose from the fear of many Egyptians who were not aligned with the Brotherhood that their lifestyles were at risk of being dictated by people they neither knew nor respected.

Third, and finally, Morsi’s fate is a powerful reminder that the consequences of challenging the Egyptian system are dire. Incompetence, corruption and limited political skill are not necessarily a threat to one's survival in that system. But the consequences of raising open-ended questions about the system itself, whether one is Islamist or secular in lifestyle and values, are certain to be direct, and brutal.

Possessing the potential to be either rewarding or catastrophic at personal and professional levels, the ultimate certainty of Egypt is that it is the Egyptian system that prevails. And when the system turns on you, as it did on Morsi, no-one in the system will question the justice, or the wisdom, of it doing so.