US President Donald Trump is sliding into an increasingly obvious pattern in his dealing with small or rogue states who oppose the United States. In his presidency so far, Trump has already picked fights with four such countries – Syria, North Korea, Venezuela, and Iran. In each case, after extraordinary bluster and threats of force, Trump ultimately refused to attack these supposedly grave threats (barring a minor missile strike on Syria in 2017).

It is now increasingly apparent that Trump, despite all his posturing, does not in fact want to start a serious conflict on his watch. Much of the world can see this now. By the time Trump got around to threatening the “obliteration” of Iran late last month, it sounded canned, and no one, not even the Iranian government, seemed to talk it seriously.

Trump has established a similar record domestically, where he frequently balloons issues into crises, usually via Twitter, only to later claim to save the day by stepping back from the brink. This cycle of drama and catharsis may sate Trump’s need for media coverage and affirmation, but it is now so predictable that when Trump shut down the US government in January, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi did not budge, nor do the Iranians seem to be taking Trump seriously. And indeed, Trump stepped back from force in Iran just as this cycle of bluff-and-retreat predicts.

Trump is constrained. The first new GOP president since the Iraq War catastrophe, he is sharply bound by the strong, nearly bipartisan desire to avoid another such conflict, especially in the Middle East.

Hawks will complain that this raises credibility problems. At this point, no one believes Trump’s threats of force anymore. He is the boy who cried wolf. This paradoxically raises the follow-on problem that Trump may strike the next rogue state he picks a fight with, just to prove to critics and the media that he is as tough as his posturing.

But the larger intellectual problem that Trump’s empty threats illustrate is dilemma of Republican foreign policy thinking in the wake of the Iraq War. Just as the Vietnam War turned a generation of Americans against “quagmires”, so has the second Iraq War. President Ronald Reagan, despite contemporary GOP mythology, did not actually use US ground troops much (Grenada is the main exception). He operated against a post-Vietnam public opinion which simply would not support extended operations in a fluid, hostile, third-world environment. When US peacekeepers in Beirut were killed, he withdrew.

Trump is similarly constrained. The first new GOP president since the Iraq War catastrophe, he is sharply bound by the strong, nearly bipartisan desire to avoid another such conflict, especially in the Middle East. And indeed, Trump himself seems to want to avoid these conflicts. For all his machismo, Trump is actually rather dovish. He enjoys diplomacy – if only for the TV coverage and ginned-up drama (see the weekend border photo-op handshake with Kim Jong-un) – and pretty clearly disagrees with the neoconservative, democracy-spreading ideology of the previous GOP administration. This has led to a mini-debate over whether Trump is a retrencher or a realist.

Trump’s personal uninterest in fighting yet another US post-9/11 war would ideally ignite an overdue Republican debate over the use of force in US foreign policy. But it has not. GOP rhetoric from Congress and from Trump himself continues to be belligerent and aggressive. Trump issues extraordinarily aggressive threats, as do Fox News hosts, and Senate warhorses such as Lindsey Graham or Tom Cotton. There is no retrencher or realist faction on the rise in the GOP. There has been little pushback on the right against Trump’s belligerence against Iran, and certainly nothing like the let-a-thousand-flowers-bloom foreign policy debate going on in the wide-open Democratic primary.

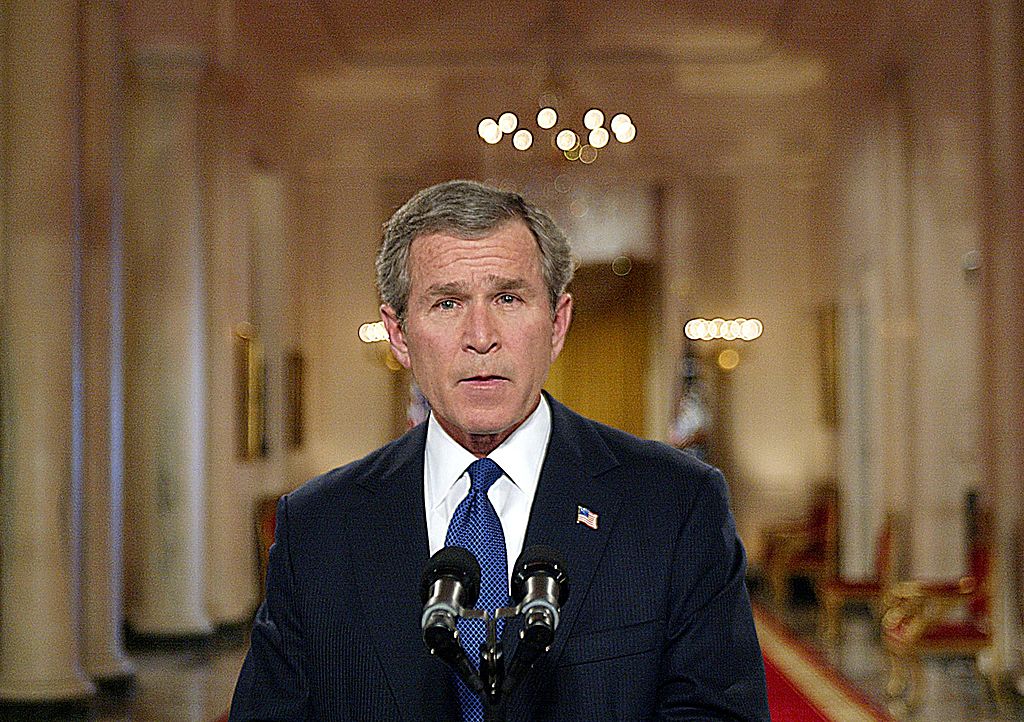

But hanging onto to the old rhetoric is a dead-end for the GOP. Trump’s extremely hawkish language but dovish policy choices illustrate the party’s post-Iraq dilemma, which it seems distinctly unwilling to address. Rhetorically, the party has not moved on from belligerent, unilateralist, American exceptionalist rhetoric. The driver of that under Trump may be nationalism, where it was neoconservatism under President George W Bush, but the swagger, grand-standing, military threats, and “omnidirectional belligerence” are all still there. There has been no post-Iraq adjustment, no more restrained rhetoric suggesting a more accommodating approach to the world. Trump seemed to promise that when he declared the Iraq War a mistake in the 2016 GOP primary. But as President, Trump’s egomania, love of drama and macho display have brought him to rhetorical excesses even worse than the neocons.

Yet there is no public support for such language. The US public quite clearly does not want another quagmire war of choice. Surely it will support the use of force if the US is attacked. But there is simply no appetite – unless it is absolutely necessary – for another lengthy asymmetric conflict.

For the Democrats, this is less troublesome. They are less prone to accept extreme extrapolations of the unipolar moment, less comfortable with force as the main tool of US diplomacy, and more willing to work multilaterally and through international organisations.

But the GOP ideologically rejects these options. It remains strictly wedded to a nationalistic, tough-guy foreign policy tone. Fox News regularly channels this “America First” unilateralism, and the Trump administration is even more disdainful of international organisations than Bush was.

All this leaves the GOP with no clear policy options other than sanctions. Its unchanged aggressive language suggests that the US should be attacking one country after another for daring to stand up to America. Going through regional organisations is dismissed, and diplomacy under Trump is mostly just the US issuing demands – as with Iran or North Korea.

Yet when it comes to following through on the aggressive rhetoric, the GOP flinches – for obvious reasons. The country opposes its threatened wars, and the GOP would suffer at the ballot box. Trump, who possesses great political instincts, senses this even if the neocons in his party do not.

So all the GOP can do in the end is argue for more and more sanctions. “Dovish” approaches such as diplomacy are ideologically unacceptable – the intellectual reckoning with the Iraq War still awaits. But the much-wanted hawkish choices of strikes would be domestic political suicide, given public opinion. The result is incoherence and a fall-back to sanctions to show toughness.

The one silver lining of the Trump victory was that he would pull the GOP away from its post-9/11 “omnidirectional belligerence” and toward realism and diplomacy. That has failed, and the cost is a running series of empty threats and foreign policy incoherence.