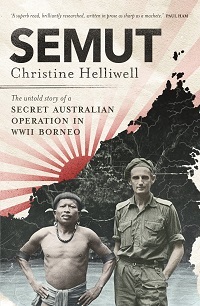

Book review: Christine Helliwell, Semut: The Untold Story of a Secret Australian Operation in WWII Borneo (Michael Joseph: Penguin Random House, 2021)

Book review: Christine Helliwell, Semut: The Untold Story of a Secret Australian Operation in WWII Borneo (Michael Joseph: Penguin Random House, 2021)

Few in Australia know that 75,000 Australian soldiers fought in the 1945 Borneo campaign. This figure is comfortably more than the 60,000 that served in Gallipoli or the 14,000 in Tobruk. History is much more than an exercise in bean-counting and Cristine Helliwell makes a compelling case for why the story of Operation Semut should be told.

Taking place behind Japanese lines in Sarawak, northern Borneo, Operation Semut stands as one of Australia’s first independent special forces operations – and certainly one of its more audacious. Led by Special Operations Australia (SOA), Semut involved parachuting several parties of Allied forces operatives into British Borneo in the final months of the Second World War.

Semut’s objective was to recruit the local Dayak people to wage guerrilla warfare against the Japanese. There was ample scope for severe misunderstandings. Most operatives had never been to Borneo, and only a handful spoke Malay, yet alone any Dayak languages. There was generally little conception of Dayaks beyond crude, racialised depictions of savage headhunters. In remoter regions under Semut’s remit, some Dayaks had never seen a white face. Relationships between Dayak communities and the British colonial administration were often tense or ambivalent.

A professional anthropologist who spent 20 months living in a traditional Dayak long house in the 1980s, Helliwell masterfully guides the reader through Sarawak’s rich cultural mosaic and fluid politics. As Helliwell explains, “Dayak” itself is an umbrella term for a heterogenous array of indigenous peoples living in Borneo. Twenty-two Dayak groups inhabited the territories in Semut’s operational purview, alongside ethnic Chinese, Malays, Eurasians and, of course, Japanese occupiers.

After having been initially accepted by local Dayaks as legitimate rulers due to their superior martial prowess, by 1945, Japanese forces had well and truly overstayed their welcome. Still, enlisting Dayak support was not a foregone conclusion. Helliwell outlines in vivid detail the painstaking negotiations – aided by bountiful servings of borak (local alcohol) – that ultimately led to Semut’s military success. Standing among the more unusual examples of early Australian military diplomacy, these negotiations necessitated the acceptance or indeed encouragement of headhunting’s revival.

A thought-provoking account straddling anthropology and military history, Helliwell’s Semut is also interesting for what it says about early Australian foreign policy, the operation taking place just a few years after the Statute of Westminster was finally adopted. By seeking to help drive the Japanese from Borneo, Semut was compatible with core Allied objectives. Where divergence occurred was through London’s attempt to use Semut as a Trojan horse to reclaim “lost property” in restoring control over Sarawak. SOA was heavily influenced by London and the Colonial Office and many of its commanders were British. The Americans were naturally often deeply suspicious of SOA’s motives.

Most if not all Semut operatives were Empire men, who saw little clear distinction between Australian and British national interests. Nonetheless, contradictions existed that would only become clearer over time. Liberating large concentrations of Australian prisoners of war at Sandakan was not necessarily a priority.

Nor was real consideration given to growing demands in Sarawak for independence or greater autonomy. There was also little appreciation or grasp of prevailing currents – European decline, rising US power and growing Asian nationalism – that would soon bring colossal change to the region. Australia’s role in helping to re-establish European control in Malaysia and (at least initially) in Indonesia, inevitably contributed to enduring regional characterisations of Australia as a “colonial” power.

How best to serve the national interests in balancing regional relationships, Western alliances and sometimes conflicting demands for self-determination would soon bedevil Australian policymakers in Indonesia, West Papua and during Konfrontasi. A different variation of the same issues confronts Australian policymakers today. Despite Semut’s tactical success, in managing these broader strategic challenges, Australia did not exactly get off to a flyer.

Helliwell’s Semut also inevitably highlights a pronounced paradox in contemporary Australian foreign policy. Australia’s interests are now squarely defined as being in the Indo-Pacific. Yet how we commemorate war continues to be largely Euro-centric, despite the litany of Second World War engagements that took place in Australia or the region – not to mention the frontier wars.

In turn, this contributes to the geographic dissonance that, in one way or another, so often sees Australia’s gaze shifted elsewhere. It was telling that Australia’s leaders were preoccupied with Ukraine at the exact time that China was negotiating a security deal with Solomon Islands. By reframing the public memorialisation of Australia’s military history to focus on events closer to home, books such as Helliwell’s Semut can engender a greater sense of Australian belongingness to the region.

Semut operatives are mostly fondly remembered today in Sarawak. Nonetheless, there is a risk that a broader reappraisal of Australia’s military history could be counterproductive in drawing attention to Canberra’s complicity in prolonging colonialism. While this possibility shouldn’t be discounted, acknowledging awkward historical truths – even if belatedly – surely serves the furtherance of mature regional relationships more than sweeping them under the rug.

Crafted from a disparate and incomplete archival record, interviews with Semut operatives and hundreds of locals, Semut is a labour of love to Borneo and its peoples. It serves as a palliative for a peculiarly Australian case of historical amnesia.