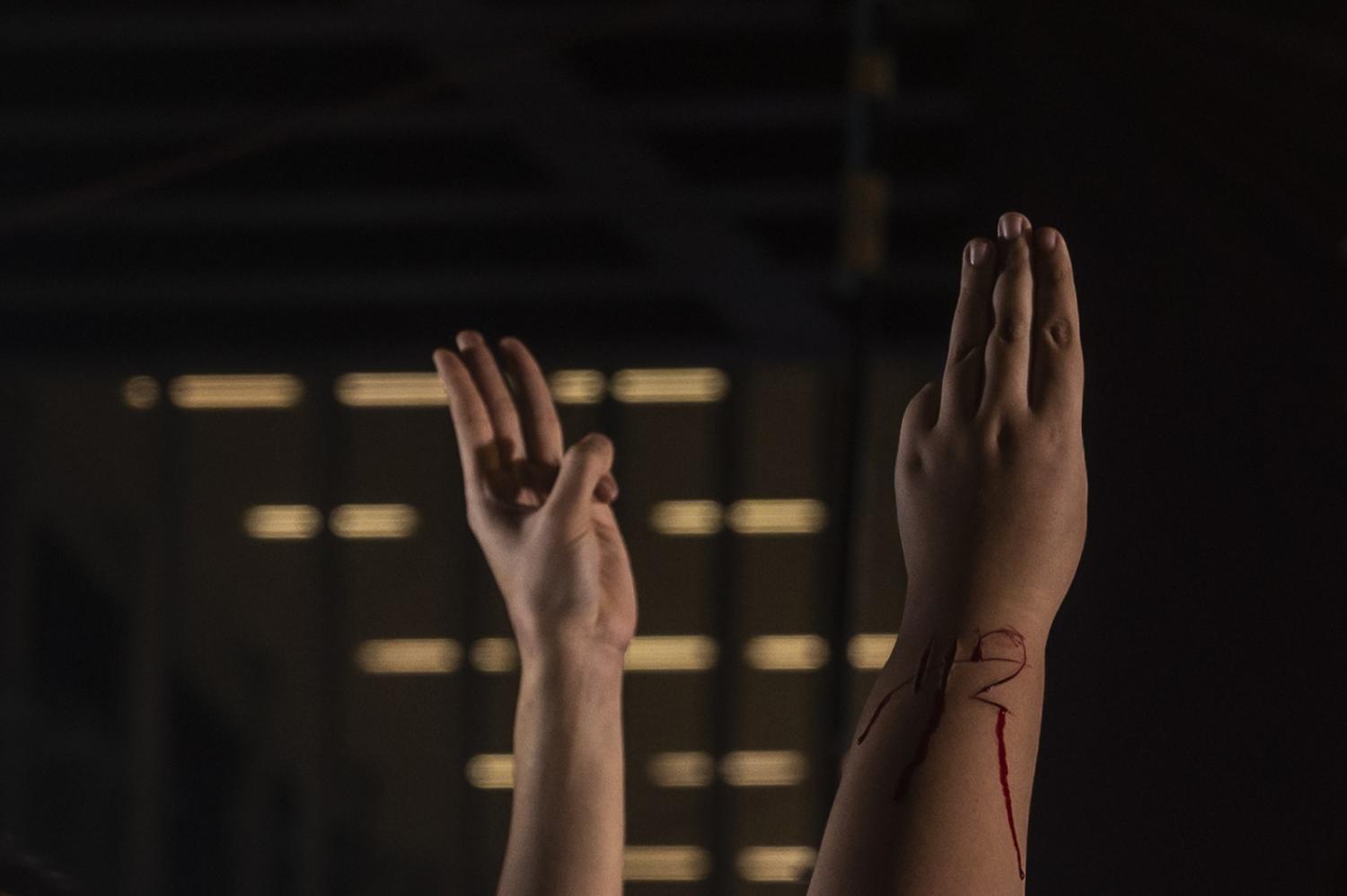

At a recent anti-government rally in central Bangkok, one of the leaders of a youth-led movement demanding sweeping political reforms carried a message etched in blood. After addressing the crowd on a rainy Sunday evening on 31 October, Panusaya “Rung” Sithijirawattanakul used a razor blade to carve the digits 112 into her forearm, struck through by a diagonal cut.

It was a startling image – not just for the blood, but for what it represented: another defiant act questioning the powerful role of the monarchy in Thailand and the repressive laws, ideals and institutions that uphold it.

The number refers to Thailand’s punitive lèse majesté law (Section 112 of the Criminal Code) that makes it a crime to defame, insult or threaten members of the royal family. The law, which carries a maximum penalty of 15 years’ prison for each offence, has been liberally used by the junta-turned-government to target activists such as Rung and other perceived critics, from politicians to pensioners. Many are facing decades-long sentences.

At great personal risk, student activists are calling for the lèse majesté law to be abolished, along with other reforms to the monarchy, shattering a long-held taboo against even anodyne discussions of the king. Among their demands, widely circulated at the height of protests last year, are that the substantial royal assets, now under the personal remit of King Maha Vajiralongkorn, be brought under public control.

In the wake of the 31 October protest, it seemed, for a brief moment, that substantive public debate on the law may be possible.

“It is time for the institution of the monarch to be spoken about openly, no matter who one is,” Rung stated in a speech last year. “It must be able to be spoken about like it is no big deal.”

In the wake of the 31 October protest, where activists gathered signatures in support of repealing the lèse majesté law, it seemed, for a brief moment, that substantive public debate on the law may be possible.

Pheu Thai, the country’s main opposition party, aligned to self-exiled former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, issued a statement suggesting it was open to amendments. This prompted a flurry of responses from other political parties staking out their positions.

Unsurprisingly, the military-backed Palang Pracharath Party stands opposed to any changes, as do coalition partners the Democrat Party and the Bhumjaithai Party. The progressive Move Forward Party, which earlier this year proposed amendments to the law that would have curbed prison terms, continues to support change.

But illustrating the prevailing sensitivity around the debate, breached but not entirely broken by ongoing youth-led protests, Pheu Thai took a series of dizzying steps back, forward and sideways, stressing they weren’t initiating reform, then finally appearing to back an inquiry. Thaksin also muddied the waters, at first writing on social media that there was nothing wrong with the law, then suggesting that the penalty was too harsh.

The confused repositioning was perhaps reflective of conflicting views within the party and a general wariness ahead of a looming election due next year. Protesters on the streets had at least succeeded in forcing parties such as Pheu Thai to articulate a response, even if it wasn’t the decisive stand they sought.

The lèse majesté law has remained a powerful tool for silencing debate. The definition of what constitutes criticism is loosely applied, anyone can file a complaint, and trials are often held in secret. The law has led to self-censorship, the banning of books, and the suppression of ideas and information. It has also been the conservative establishment’s method of choice for dispatching its enemies on even the most absurdly founded charges.

A wave of lèse majesté arrests and prosecutions followed the 2014 coup, but were halted in 2018, reportedly at the instruction of the king. But with anti-government protests hitting fever pitch last year, the law is being wielded with a vengeance once again.

A recent constitutional court decision equated protesters’ calls for royal reform with an attempt to overthrow the institution, ruling that it violated the constitution.

Some 155 people were charged from 24 November 2020 to 3 November 2021, according to Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR). Pro-democracy protest leaders have been systematically targeted, with many cases brought by royalist groups formed to police online expression. Earlier this year, a woman in her 60s was imprisoned for a record 43 years for posting audio clips deemed critical of the monarchy.

But while the law is supposed to shield the palace from criticism, it often only draws more attention to the extent of anti-monarchy sentiment. As documented by groups such as TLHR, recent charges have been laid against people for burning, defacing or removing portraits of the king. Several minors also face charges, including a 17-year-old for wearing a crop top that mimicked the monarch’s eccentric fashion.

Subtle acts of dissent – staying seated during the royal anthem, for example – continue to be reported. But royalists, who frame their defence of the lèse majesté law as a matter of national security, retain powerful backing. A recent constitutional court decision equated protesters’ calls for royal reform with an attempt to overthrow the institution, ruling that it violated the constitution.

This troubling verdict is a blow to the youth-led movement, whose open criticism of the king has been a seismic development in Thailand.

But even arch royalists must privately admit that the carefully cultivated image of the king as semi-divine and indispensable is a mask that is slipping.