The US base on the island of Diego Garcia, in the middle of the Indian Ocean, is among the most important US military facilities in the world, and is the foundation stone of the US presence in the Indian Ocean region. It’s been a vital element in Australia’s strategic position in the region for almost 50 years. But the dispute over ownership of the island is now creating serious uncertainties over the continued long-term US military presence. Australia’s position on the controversy is becoming increasingly untenable and now needs to be reviewed.

Diego Garcia is just one of some 60 tropical islands in the Chagos archipelago. In 1965, the administration of the archipelago was transferred from Mauritius, in somewhat dubious circumstances, shortly before Mauritius gained independence. In 1973, the last of the workers who serviced the coconut plantations were removed from the island and Diego Garcia was leased to the United States for military purposes. Britain retains notional administration over the now otherwise uninhabited archipelago, as the British Indian Ocean Territory.

Virtually since independence, Mauritius has claimed sovereignty over the islands, but its campaign to regain them from Britain is now gathering steam. In 2017, the dispute was referred to the International Court of Justice, which delivered an advisory opinion in firmly favour of Mauritius. In May this year the United Nations General Assembly, by an extraordinary margin of 116 for to 6 against, voted on a deadline for Britain to return of the territory to Mauritius. Australia was one of only a handful of countries that supported Britain. The UN deadline predictably passed on 22 November without any action or even formal response from London.

Mauritius will continue to campaign for the return of the Chagos. The loss of support for Britain (and the United States) by traditional alliance partners in the UN is startling and will further embolden those campaigning for return of the islands. Mauritius has previously relied on polite diplomacy to pressure Britain, but that may now change.

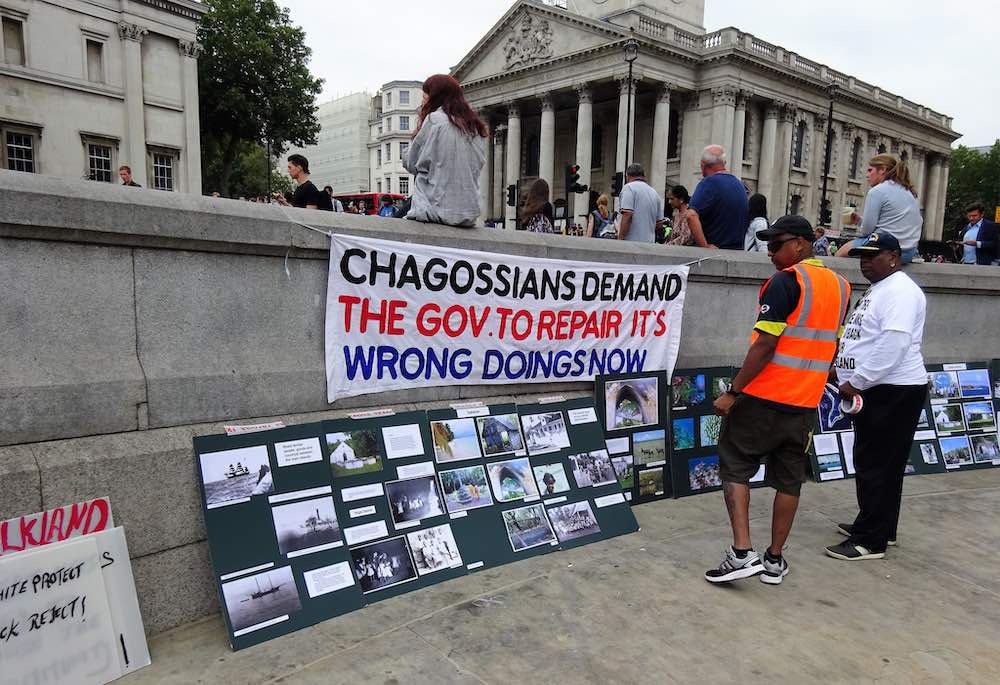

We are likely to see Mauritius ramping up its tactics to embarrass Britain and the United States over the issue. This includes plans to send a ship with displaced islanders and their descendants to land on the disputed islands, which will inevitably be interdicted. This and other tactics could get ugly, creating real moral questions over British and US claims to support for the so-called “rules-based order”.

For decades, Australia has given unquestioning support for Britain’s position on sovereignty, therefore to the legitimacy of the US base on Diego Garcia. But perhaps we should ask how long we can afford to ignore Mauritius’ claims. Indeed, there is a danger that the longer the dispute goes unresolved the more entrenched Mauritian claims may become. But there may be a window to reach a negotiated solution that gives Mauritius most of what it seeks while also allowing the US base to continue for the foreseeable future.

The Chagos dispute involves several separate but related issues: questions of formal sovereignty; the right to exploit the islands and their economic exclusion zones (EEZs) for tourism and marine resources; the right of Chagos islanders and their descendants to return to the islands for visits or permanently; and lastly, of course, the continued operation of the US base on Diego Garcia.

But London refuses to enter into negotiations with Mauritius on any of these issues. Washington takes the convenient position that it’s Britain’s problem.

For its part, Mauritius has long focussed on trying to persuade London about the question of sovereignty. But it has not substantively engaged with the United States, which is the real party in interest. One wonders how long Britain would hang on to the Chagos if the United States didn’t need the base.

None of this is helpful in resolving the controversy. Indeed, these problems are resolvable.

The United States and its allies want continued military use of Diego Garcia, unimpeded by political restrictions or security concerns from local inhabitants or economic activities.

But the Mauritian government (in contrast to its previous stance) has now made clear that it does not seek to evict the US from Diego Garcia. Mauritian officials acknowledge that Mauritius could give watertight guarantees on security of tenure of the base for a “very long” time. Some senior figures even privately concede that Mauritius could consider regaining sovereignty over the archipelago minus Diego Garcia and perhaps even some nearby islands.

Given the flexibility apparently expressed in Port Louis, it seems hard to believe that acceptable new arrangements could not be reached that deals with sovereignty, economic rights and the Chagos islanders.

India has a key role in resolving the issue, and its political influence in Mauritius cannot be overstated. Delhi long supported Mauritius’ sovereignty claims and opposed the US military presence. But it now recognises the value of the US base, and indeed is said to quietly use the base itself. It is therefore in India’s interests to reach an acceptable resolution.

Undoubtedly, future arrangements may not be as perfect for the US and its allies as having unimpeded use of an uninhabited archipelago notionally administered by Britain. But that colonial era may soon end. It may now be time to put in place a new set of arrangements.

For Australia, the US military presence in the Indian Ocean, anchored by Diego Garcia, is vitally important. That creates an imperative to use our relationships with all the parties to facilitate a mutually acceptable outcome. Ignoring the problem is no longer an option.

This article is part of a two-year project being undertaken by the National Security College on the Indian Ocean, with the support of the Department of Defence. The author recently travelled to Mauritius.