Book Review: The Last Colony: A Tale of Exile, Justice and Britain’s Colonial Legacy by Philippe Sands (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2022)

Book Review: The Last Colony: A Tale of Exile, Justice and Britain’s Colonial Legacy by Philippe Sands (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2022)

Popular understanding would have many believe that Britain’s vast empire was decolonised in the post-Second World War era. Former colonies across Africa, South Asia, the Pacific, the Caribbean and beyond opted to chart their own course during the Cold War – many joining the Non-Aligned Movement. Despite these nations shaking off the chains of colonialism and joining the burgeoning international community, in an exceptional set of circumstances in 1965, Britain created one last colony – the British Indian Ocean Territory, or BIOT.

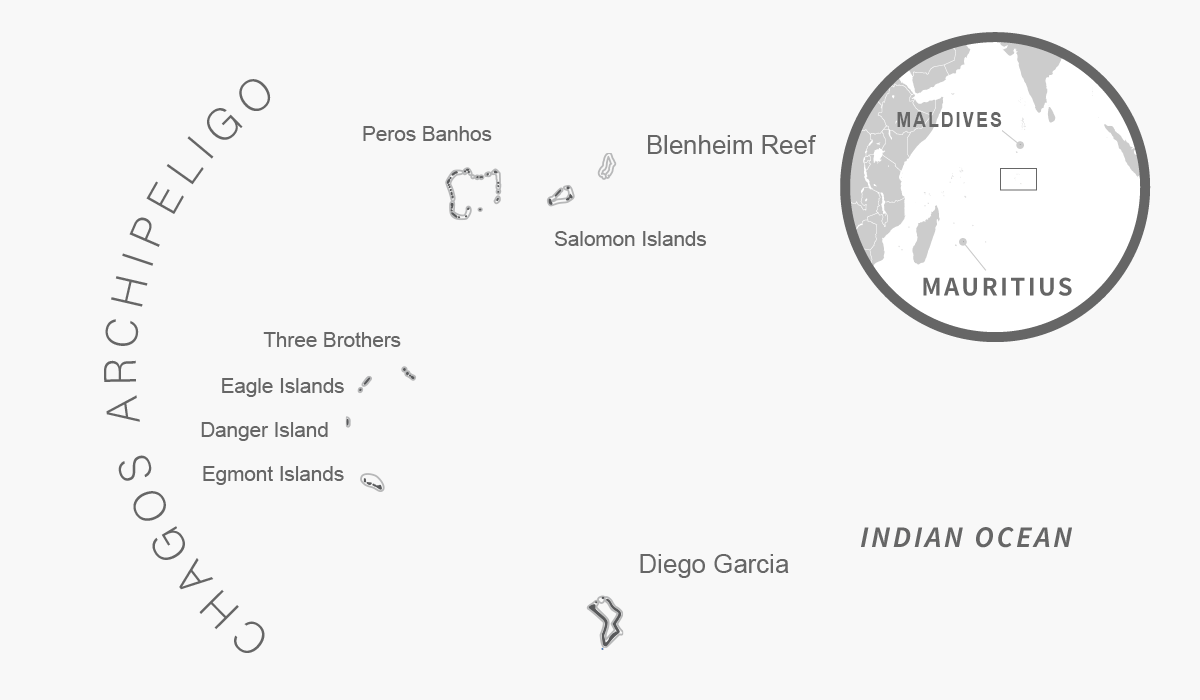

In the years before Mauritius attained its independence in 1968, one of its archipelagos, the Chagos Archipelago, was illegally detached to create BIOT. At that time, the United States was seeking Indian Ocean islands to supplement its array of bases. The island of Diego Garcia in the Chagos Archipelago was found to be the most suitable due to its location, its topography, and the expectation that British ownership would safeguard US interests. So it proved, Britain detached the archipelago before Mauritius achieved independence and expelled the entire population of Chagos by the early 1970s.

These problematic British decisions have now come home to roost.

Philippe Sands’ new book The Last Colony: A Tale of Exile, Justice and Britain’s Colonial Legacy provides a ring-side seat to Mauritius’ legal and political efforts to regain the Chagos Archipelago as part of its sovereign territory. Sands, a prominent lawyer, academic and author, was retained by Mauritius in its legal strategy against Britain. Sands’ work – informed by his proximity to the action – provides an insight into not only the history and topography of the remote islands, but also the decline of Britain’s empire and the development of modern international law.

Much more than just a chronology of this sovereignty dispute between Mauritius and the United Kingdom, the book also delves into Sands’ own affinity with international law and the experience of Chagossians, in particular of Liseby Elysé. Sands provides a forceful and visceral rebuke to the very notion of the existence of the BIOT, characterising it as an illegal and racist enterprise.

Whether or not Sands had an inkling of developments, in the months after his book was released a startling change has taken place. This month, on 3 November, Britain announced both it and Mauritius had decided to “begin negotiations on the exercise of sovereignty over the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT)/Chagos Archipelago”. Prior to this announcement, Britain had flatly refused to entertain speculation that it was other than steadfast in its assertion of sovereignty over BIOT.

This announcement, made by James Cleverly, Britain’s Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs, adds that the “UK and Mauritius have agreed to engage in constructive negotiations, with a view to arriving at an agreement by early next year”.

Thus, in part due to the tireless efforts of Sands and many others, Britain’s “Last Colony” may soon be no more. But, until then, Sands’ book is a potent exposé of Britain’s double standards when it comes to human rights and international law.

Of particular note are the six plates, illustrated by Martin Rowson specifically for Sands’ book, which depict Elysé navigating her way through the various legal, political and historical symbols that foreshadowed and interacted with the Chagos Archipelago issue. These rich and vivid (even if greyscale) plates spotlight the myriad individuals, entities and forces that both displaced her, and that may grant her the right of return.

As for Australia, its support for BIOT in international fora does not escape Sands’ ire. He rebukes Canberra’s long-standing support for British sovereignty, arguing that “Australia, itself a former British colony, gave a fair impression of ‘abused child syndrome’, a victim turned perpetrator”. Indeed, as others have written in The Interpreter, Australia’s stance on the dispute is untenable. The Albanese government has not yet been forced to nail its colours to the mast when it comes to the BIOT, as the Liberal government was forced to do in 2019 when it sided with Britain at the UN General Assembly.

Sands does acknowledge briefly that, when it comes to the Chagossians seeking to return to the Archipelago, their views are not homogenous. While many support Mauritius’ claim for the Archipelago (as Mauritius has promised them resettlement if/when it regains sovereignty), others would prefer to return to a British Chagos, some are agnostic so long as they can return, and a smaller group advocate for the creation of a new nation-state. As Britain and Mauritius begin to negotiate, Chagossian self-determination, rather than Mauritian self-determination, may become a complicating factor.

Sands’ book is an insightful text for not only Chagos-watchers, but also for those interested in Indian Ocean geopolitics, decolonisation and international law. Sands’ seat at the bench provides for an exclusive and personal take on the Chagos. It delves into the work of an individual whose efforts may yet succeed in contributing to decolonising the last remnants of Britain’s empire, and redrawing international boundaries.