Book Review: Australia’s China odyssey: from euphoria to fear, by James Curran (UNSW Press, 2022)

December 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of Australia-China diplomatic relations and James Curran’s Australia’s China Odyssey provides an opportune moment to reflect on how and why we have arrived at this current juncture of bilateral relations. In many ways, as Curran succinctly documents the highs and lows of the relationship, the reader is challenged to take a deep look into the Australian psyche vis-à-vis China, and perhaps, the wider Asia-Pacific. Are we, as Australians, so narrow in our focus and mired in the politics of every day, so much so that we cannot increase our aperture when looking at China? That is, can we not see China beyond simply as a trade partner or national security threat?

Taking us behind the scenes to narrate the five decades of Australian prime ministers and their relationship with Chinese leaders, Curran provides a fascinating perspective on leaders’ outlook and foibles.

Yet inescapable in this the focus on individual personalities set within the broader context of war, alliances and modern history is to favour a story about men. Certainly, that is how most Western histories have evolved and oft-been told.

If we look at the gender ratio in key Australian government areas involved in Australia-China relations, for example, foreign affairs, defence and national security, women are underrepresented in the workforce. One glimmer of hope is that while women now have equal or near-equal representation in leadership positions in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the department has suffered considerable cuts under the previous Liberal Coalition governments. Thus, there are fewer opportunities for women in leadership in the areas of diplomacy as the department shrinks. Moreover, a 2019 Lowy Institute paper found that women were underrepresented across the Australian intelligence community, including at the senior executive levels where it was well below the Australian public service average of 45 per cent (in 2018).

If gender imbalance in Australia’s international relations sector is a historical and persistent problem, it is no surprise that the modern history of Australia-China relations privileges the male perspective.

Why is it important to have gender diversity – and for that matter, cultural and linguistic diversity – in Australia’s international relations sector and for Australia-China relations? The lack of diversity across key public and international facing institutions presents huge obstacles when addressing the complex nature of our relationship with China, let alone with the world. It leads one to question whether Australia’s China policy would have taken such a rapid securitisation outlook in recent years had the Australian intelligence community been more gender and culturally-diverse? And would we be left with this binary position: trade partner or security threat?

Diversity in these key intelligence institutions can create “a synergy of different perspectives” to address complex problems. Diversity will also increase a greater range of hypotheses and potential policy interventions.

We may dabble in hypotheticals as to what may have been, but Curran’s portrayal of Australian prime ministers does indicate that Australia’s relationship with China is in some ways shaped by the rapport between the countries’ two leaders. The warmth and friendship struck between Bob Hawke and two Chinese leaders, Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, is extraordinary and unimaginable today.

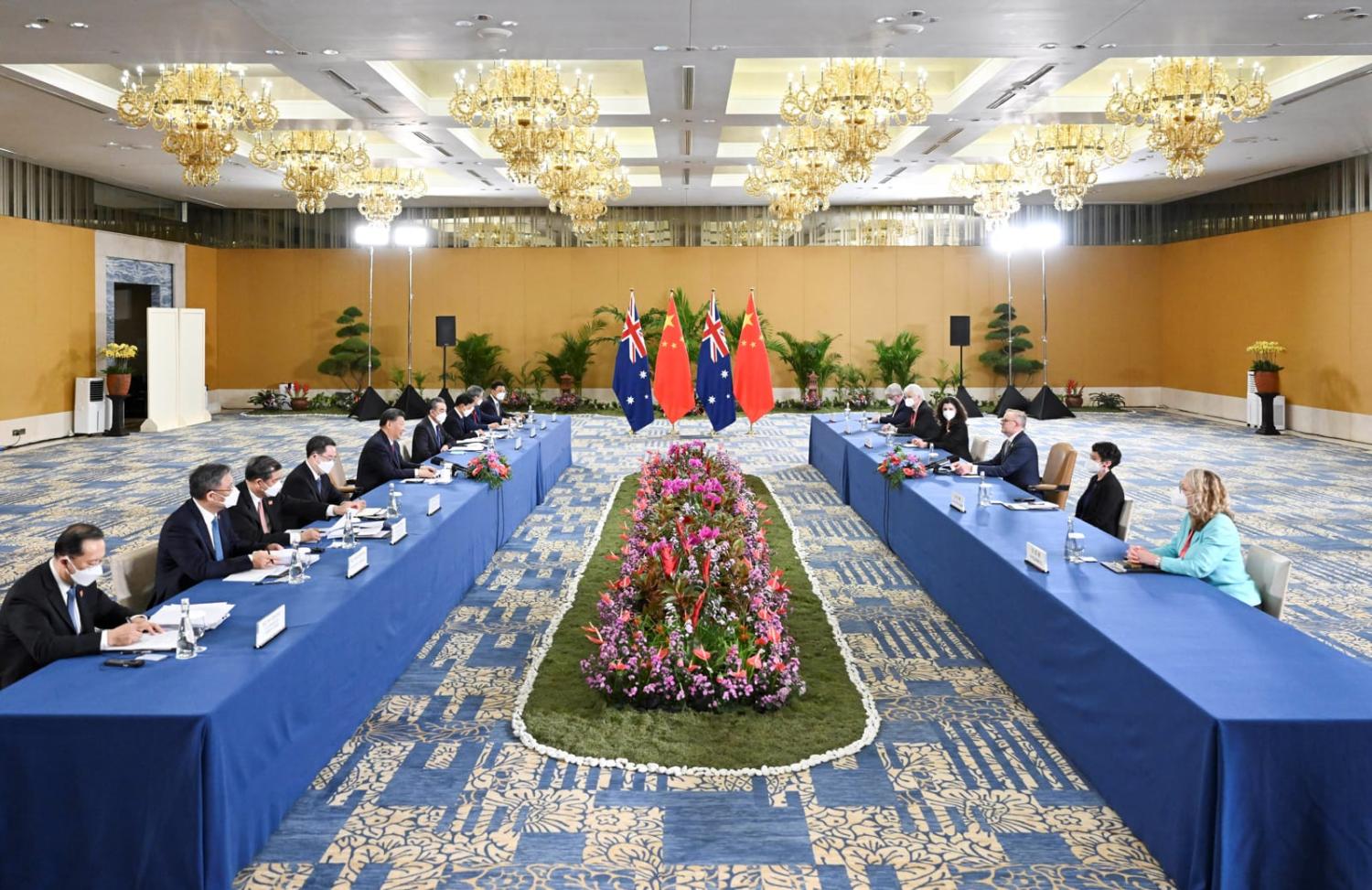

Curran quotes from Julia Gillard’s memoirs to show how she approached bilateral relations: “at the end of the day,” Gillard writes, “for all the machinery, doctrine, commentary and academic debate that swirls around foreign policy, in execution it is two or more individuals, leaders of nations, coming together to see if they can find common accord.” If we use such measures to assess the outlook of Australia-China relations, we would be hard-pressed to find much of a silver lining. Compared to his predecessors, Xi Jinping lacks the depth and character seen in Jiang Zemin, for example, where Jiang’s love for spontaneous singing and performing is well-documented.

Australia cannot return to the halcyon days of the late 1980s to mid-2000s of Australia-China relations, despite the interruption of Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989. But would Australia want to when the euphoria of those two decades was solidly rooted in the booming trade between the two countries? Surely for the longevity of any relationship, it must expand to more than just a single issue of commonality. And this is perhaps where the earlier focus on trade has sucked out much of the oxygen that could have been diverted to nurturing other areas to ground the relationship. In areas of people-to-people cooperation, such as supporting the international Chinese student community in Australia beyond the university is sorely lacking, highlighted by the pandemic.

The outlook for Australia-China relations will tread a certain path given as Curran notes “Canberra is tightly tucked into the blanketing embrace of US Asia policy” where now much of Australia’s China policy is refracted through the US-China lens. While the Labor government has recently changed the tone on Australia’s diplomatic engagement with China, it is still very much influenced by the “same senior intelligence and defence officials who have dominated Australia’s policy response to China” as Curran writes. That is, a select group of officials lacking gender or cultural and linguistic diversity will likely commit Australia down the same well-worn path of trade versus security with little imagination to push other areas of bilateral relations.