This is a short edited extract of the Lowy Institute Analysis The point of no return: The 2020 election and the crisis of American foreign policy by Thomas Wright, published on 2 October 2020. You can read the full Analysis here.

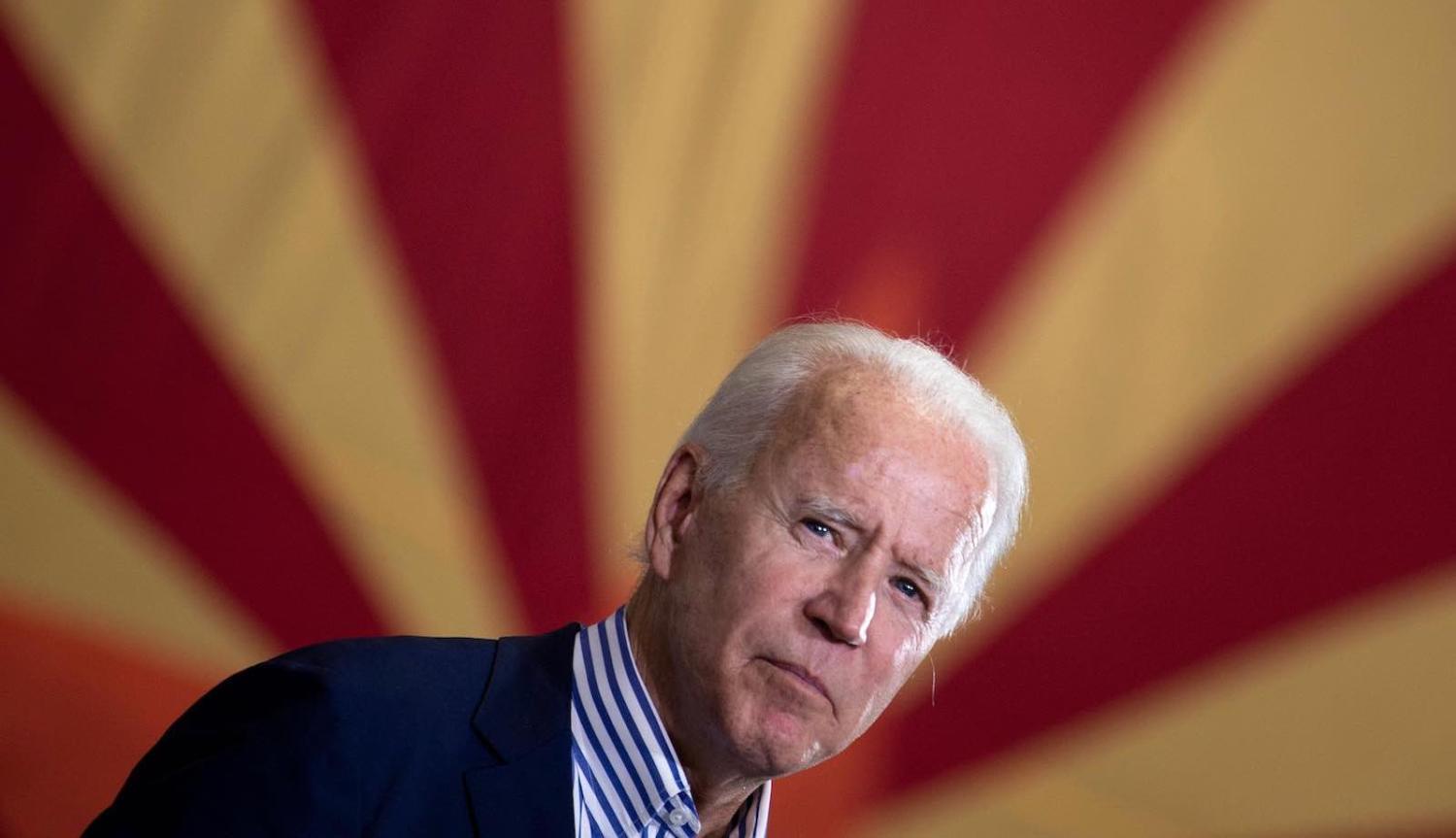

The question about Joe Biden is not how he is different from Donald Trump. That much is obvious. It is whether he will be different from Barack Obama. Will a Biden administration be a third Obama term, or will it be distinctive in its own right?

Biden is an enthusiastic advocate of US alliances and American leadership. Will the United States be able to reconstitute the international order? Will Biden continue down the path of great power competition with China and Russia?

Most important of all, can Biden set the stage for a renewal of American leadership? Or will history remember his administration as a brief and futile last gasp of the foreign policy establishment that was preceded and succeeded by a more durable nationalist alternative?

A number of leading Democrats believe that the world has changed in fundamental ways in the past eight years since Xi Jinping came to power in China, Vladimir Putin returned as Russia’s president and Obama was re-elected.

Biden represents a return to America’s traditional post-Second World War foreign policy. He has built a tent large enough for Republican Never-Trumpers, Democratic centrists (of whom he is one), and progressives. He will seek to undo much of what Trump has wrought — to rejoin the Paris Agreement on climate change, to try to revive the Iran nuclear deal, to work with other nations on combatting Covid-19, and to resume US support for its allies.

But in other ways, Biden is an enigma. His differences from Trump will not suffice as an organising principle for his foreign policy. There have been hints. Biden has called Saudi Arabia a “pariah state”. He has taken a tough line on China. He has argued that globalisation must serve the middle class. He is an avowed transatlanticist, but will he continue Obama’s policy of pushing Europe to spend more on the military, even as the pandemic exerts downward pressure on defence budgets?

Much of this will be determined by how Biden straddles a series of substantive debates between centrists in the Democratic Party. The progressive-centrist debate received considerably more attention in the primary campaign, but the intra-centrist debate has taken place in parallel, with two schools – a restorationist group that holds to the Obama worldview, and a reform group that questions some of the basic assumptions of that administration, on China, globalisation, the Middle East, and the long-term future of the liberal international order.

The first half of a Biden term is likely to be defined by a struggle between these two worldviews. The coronavirus crisis will cast a shadow over all of this and raise fundamental questions about the future of the global economy, cooperation with China, and the future of international institutions. The debate on these issues has barely begun.

The Obama baseline

Obama’s worldview often appeared contradictory. He was a liberal who believed in progress and the necessity of American leadership in bringing it about. He also had realist instincts; he worried about US actions creating more problems than they solved. By the end of his presidency, it was clear the classical realist impulses had prevailed, at least when it came to military intervention and great power competition.

Obama would privately say his policy was “don’t do stupid shit”. Others who served in his administration, including Clinton, were frustrated – ‘“Don’t do stupid stuff” is not an organising principle”, she said, much to Obama’s annoyance.

When it came to foreign economic policy, Obama was something of a traditionalist. He was proud of the role his administration played in responding to the financial crisis in 2009. Ultimately, he was a believer in globalisation and did not seek to radically change or reverse it.

The intra-centrist debate

One group of Democrats continues to believe in this approach and has not fundamentally changed their worldview since the Obama administration. They continue to believe that the arc of history favours the United States, they are sceptical of military interventionism, they do not want US foreign policy to be defined or constrained by geopolitical competition, even though they accept the United States must stand up for its interests against China, and they continue to believe in the economic and geopolitical benefits of globalisation. This group can be described as restorationist.

Yet in the past four years these debates have expanded and deepened. A number of leading Democrats believe that the world has changed in fundamental ways in the past eight years since Xi Jinping came to power in China, Vladimir Putin returned as Russia’s president and Obama was re-elected. Nationalist populists have gained power in several countries, authoritarian regimes have used new technologies to modernise the tactics and tools of repression and control.

Democrats, in particular, feel that there is much to learn from Canberra when it comes to tackling political interference.

Autocratic leaders have become more assertive and aggressive internationally. Shared problems, such as climate change and pandemics, have worsened, but international cooperation has become harder to achieve and to explain to domestic audiences. The conviction that the world has fundamentally changed has led this group to revisit the core tenets and assumptions of Democratic foreign policy in at least four areas: China, cooperation among democracies, foreign economic policy, and the Middle East. They can be called the reformers.

Learning from Canberra

Australia is something of a unique case. Along with Abe Shinzo’s Japan, Australia has handled Trump better than any other liberal democracy, albeit after a rocky start with the terse phone call between then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and Trump. Australia has benefited from the fact that it has a trade deficit with the United States and it also spends in excess of 2% on defence. As a conservative, Scott Morrison worked well with Trump administration officials and Australia was an early mover on pushing back against Chinese political interference and in placing restrictions on Huawei.

If Biden wins, he can be expected to continue to deepen the US alliance with Australia. This is something restorationists and reformers can agree on. Democrats, in particular, feel that there is much to learn from Canberra when it comes to tackling political interference. They are also keen to deepen relations between democracies in Europe and Asia, and Australia will play a key role in that effort. The Australian government is likely to favour Biden taking a tougher approach to China than did the Obama administration, so it may find itself weighing in to the restorationist versus reform debate.

Biden’s record as a senator, vice president, and presidential candidate strongly suggests he will have an open mind about how to implement his worldview – he will likely encourage and adjudicate the debates in his team.

The challenge for a President Biden will be whether he can make good use of these four years to firmly place American leadership on a more sustainable footing nationally and internationally. Otherwise, his victory may just be a stay of execution for the postwar order.