The face of New Delhi’s political heart, Lutyens Delhi (named after the British architect Edwin Lutyens who designed it) is a place of broad boulevards, imposing red sandstone buildings, flowing fountains and wide swathes of green space. Built between 1911 and 1931, the area was intended to be the centre of administration for the British Raj. It contains the main government buildings – the Rashtrapati Bhavan (formerly the Viceroy’s House), the Secretariat Buildings and Sansad Bhavan, or Parliament House. Even after the British left, Delhiites remained proud of, and awestruck by, its architectural beauty.

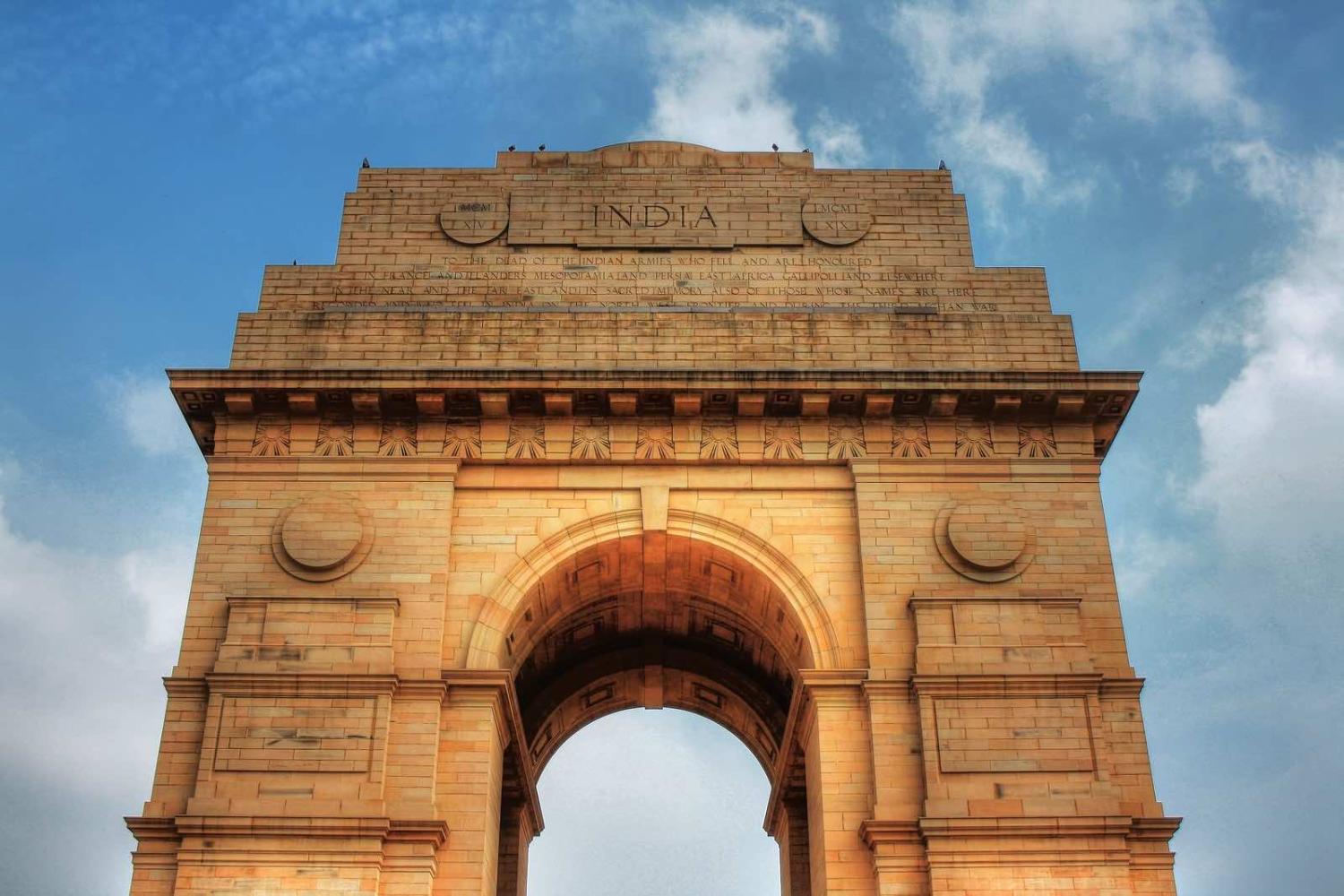

Rajpath, a broad boulevard that serves as a kind of spine for the city, runs between India Gate and Rashtrapati Bhavan, the president’s official residence, continuing for around three kilometres, mostly with two separated lanes – a rarity in New Delhi. It is, particularly in a city that can be gritty and unwelcoming, a respite for all sectors of society, surrounded by greenery and free of the usual mad traffic tangle of the capital. The area around India Gate is a drawcard for tourists and locals, who come to marvel at the war memorial, eat ice-cream and take in the ever-present nightly festive atmosphere.

The project has already proven deeply controversial; earlier this year the Supreme Court finally gave it the go-head after 28 hearings in eight months.

But things are changing. The government has launched a major redevelopment project, which entails demolishing a host of old buildings and redesigning the area. Soon, visitors to Delhi will be greeted by a significantly altered centre. A little over a decade since the capital underwent building work for the Commonwealth Games, it is again being revamped, with a large part of the central boulevard roped off and dug up.

Known as the Central Vista Project, the work will reshape and reformat the area – including more space to house the prime minister and vice president and a new parliamentary building.

The project has already proven deeply controversial; earlier this year the Supreme Court finally gave it the go-head after 28 hearings in eight months. The work has attracted criticism from within India and abroad, seen as an expensive “vanity project” while so many Indians are suffering through the pandemic.

There are also concerns that replacing the 1930s pre-Independence cultural and architectural landmark with something new is another plank in the Modi government’s ambitious agenda to reframe modern India. What better way to do this than with new buildings and a new urban space that can be showcased on websites and Instagram for years to come?

The plan includes the creation of a new triangular-shaped parliamentary building that will sit alongside the existing one, the razing of institutional buildings along Rajpath, the construction of multi-storey office blocks along the boulevard, and a reallocation of space to the prime minister’s official residence. In total, around 460 000 square metres are reported to be in line for demolition.

The government and planning bodies have released little of the detail – although Urban Affairs Minister Hardeep Singh Puri did tweet out photo updates last week.

Perhaps the most controversial element of the project is the fate of three much-loved buildings: the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, the National Museum and the National Archives annexe. The last has provoked heated resistance from historians deeply concerned about the fate of the annexe, including the many fragile and ancient texts it holds, some dating back to the 16th century Mughal Empire.

Sonia Gandhi and West Bengal’s leader Mamata Banerjee were among 12 opposition party leaders who recently wrote to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, urging him to halt the construction and instead redirect the funds towards medical care and Covid-19 vaccines. Rahul Gandhi – who is emerging as a fiercely vocal critic of Modi on social media – labelled the project “criminal wastage”. Another letter to Modi, signed by 76 public intellectuals from around the world, including artist Anish Kapoor and the director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, criticised the project as ideologically driven, particularly during a pandemic, endangering workers’ lives and squandering resources.

Other detractors claim that the funds for the project come at the expense of welfare schemes and spending on education, healthcare, social protection and women’s issues, which have seen their budgets cut. Environmentalists say that with only limited environmental regulations in place, it’s feared that the work will wreak long-term damage to already compromised areas.

To potentially relinquish part of what makes Delhi’s cityscape unique will be a loss that will change not just the face of the city, but will erase part of its living history.

However proponents of the project say it brings much-needed jobs and will rejuvenate the area. Urban Affairs Minister Puri says, for example, the texts currently housed in the National Archives annexe will be shifted to the North and South blocks of the project. He also confirmed that only two components of the plan have been approved to date and are currently underway: the parliament building and the widening of the Central Vista stretch, which appears to be the reimagined Rajpath.

The plans have not been released in their entirety, but there have been claims that the project, which includes the new parliament building, office blocks and prime ministerial residences, is budgeted at around $US2.7 billion, however the government has claimed this spending will be spread over several years.

The Urban Affairs minister insists that people will still be able to enjoy their nightly ice-creams at the green space once the park around India Gate is reopened. But to potentially relinquish part of what makes Delhi’s cityscape unique will be a loss that will change not just the face of the city, but will erase part of its living history: the lasting legacy of colonisation.

But perhaps that’s the point.