In 2000, China, Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand concluded an agreement to begin clearing the Mekong River of obstacles so that cargo vessels could travel from southern Yunnan to the old royal capital of Laos, Luang Prabang. Neither Cambodia nor Vietnam, the other two riverine countries, were involved in the discussions leading to the agreement.

Between 2000 and the end of 2002, Chinese work teams cleared enough of the obstacles in the river between Guanlei in the far south of Yunnan province and Chiang Seen in northern Thailand. This allowed navigation to begin on a regular basis during periods of high water. When I travelled down this section of the river in 2003 Chinese work teams were still engaged in further clearance operations. (I discussed the issue of navigation my 2007 Lowy Perspectives paper, The Water Politics of China and Southeast Asia II. Rivers, Dams, Cargo Boats and the Environment.)

But the planned clearance of the river downstream of Chiang Sean and so to Luang Prabang, and in particular of the major concentration of rapids at Khon Pi Luang just above Chiang Khong township, did not take place. The Thai government became concerned about border demarcation issues that might arise if obstacles in the river were removed, raising doubts about the precise location of the thalweg, the lowest point in the river that would determine where sovereignty lay. At the same time, local civil society groups in regions close to the river became very active in opposing any further clearing on environmental grounds.

This was where matters appeared to rest until 2016 when the Thai government authorised a Chinese firm, Chinese Communications Construction Company (CCCC), to carry out an initial survey of obstacles to be removed while preparing an environmental impact statement.

Who would benefit if the original plan to clear the river for navigation to Luang Prabang actually occurred?

The extent of opposition to clearance of the Khon Pi Luang, rapids and the ham-fisted approach of CCCC representatives in seeking to overcome local opposition when they called the uncleared section of the river “primitive” is captured in detail here. Beyond the undoubted reasons for environmental concern linked to the issue of whether the Khon Pi Luang rapids might be cleared, the broader question is who would benefit if the original plan to clear the river for navigation to Luang Prabang actually occurred?

As I argued in my 2007 paper there is no question that Chinese vessels and interests have been the main beneficiaries of the link already established between southern Yunnan and northern Thailand. This is chiefly because Chinese vessels are more powerful and more numerous than competing Lao vessels and the trade that takes place is dominated by Chinese firms, including those operating in Thailand’s Chiang Rai province.

So it is not unreasonable to conclude that if further clearance did indeed take place, it would be Chinese vessels that would reap the main benefit. In doing so they would further enhance the sense that is already growing that China is playing a dominating role in the Mekong below its own borders. This point is well made in an NPR article noting the calculated display of power by Chinese gunboats travelling into the Golden Triangle region well below its own borders. Eliott Brennan also notes this issue more generally (China eyes its next prize: the Mekong).

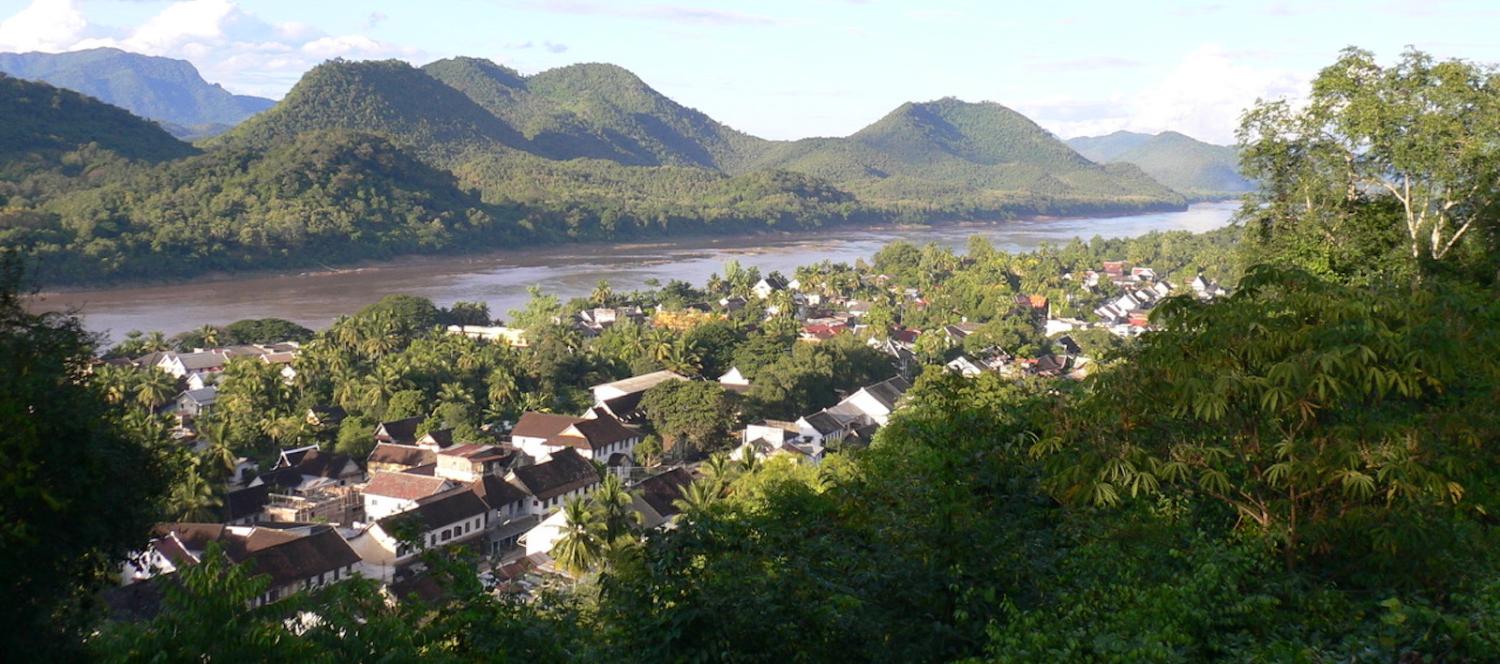

The fight to preserve the Khon Pi Luang rapids seems likely to continue for some time. More generally the commercial case for enhancing navigation of the Mekong to Luang Prabang seems dubious at best. While there may be a market for Chinese goods in Luang Prabang, there is no obvious commodity that could be backloaded for sale in China.

What’s more, expanding road systems between China and Laos and eventually a rail link will be more useful in developing commercial ties between the two countries. In short, clearing the Mekong for further navigation, if it ever takes place, seems to fit Chinese plans to expand its influence rather than to develop major commercial links with its small neighbour.