2020 could be defined as a year of global crises – health, political, environmental and economic. The G20 is caught among all four, and how the forum responds raises questions about whether it is facing its own existential crisis.

With a chaotic US election and presidential transition as well as a deepening Covid-19 pandemic grabbing global headlines, it would be easy to miss that the G20 Saudi Arabia is well underway. Later this month, at the end of a year of virtual meetings, G20 heads of government will log into Zoom and negotiate the final terms of the Saudi Arabia Leaders’ Communiqué.

There is a lot of weight – more than usual – on the success of this year’s G20 Leaders’ Summit. There are two reasons for this. The first is that the G20 is facing its first real crisis since the forum was established to tackle the 2008 gobal financial crisis, and this has tested its continued relevance and effectiveness. Secondly, Saudi Arabia’s presidency means that it faces greater scrutiny than in previous years.

Since the global financial crisis, the mandate of the G20 has broadened, and its civic engagement ballooned. Engagement groups are increasingly attempting to tackle challenges beyond global economic cooperation. A broadened mandate without structured mechanisms is always going to be a challenge, despite the agility that goes with having minimal bureaucracy.

The 2020 world of Zoom diplomacy, though, may have helped the G20 overcome some of its increasingly problematic shortcomings – one of them being that meetings themselves had become the purpose of the forum, rather than the platform or mechanism to propose and debate policy. With the world thrust into navigating online meetings, the focus and frequency of meetings increased. No longer required to secure funding and travel, barriers to attendance were reduced and agendas sharpened. The W20, which proposes policy recommendations to enable women’s economic contribution, met at least three times as much as in previous years.

Perhaps it is a deeper structural problem that women do not have a place at the decision-making table among the world’s most important economies. This includes Australia.

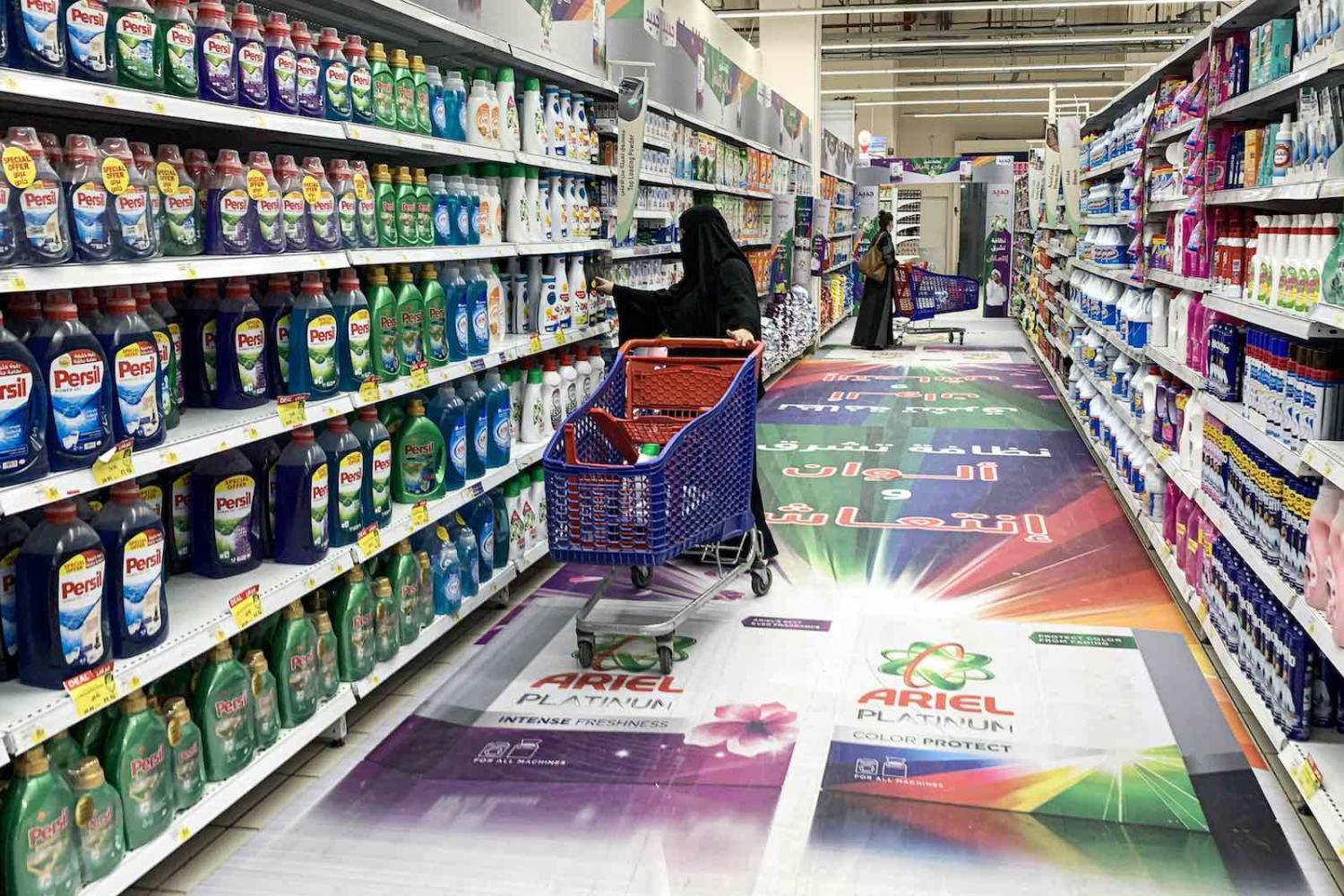

That the G20 went virtual meant that Saudi Arabia faced an even greater challenge in overcoming its own controversies and demonstrating to the world that its liberalisation was more than a public relations exercise.

Not in the five years of my attending G20 meetings in Turkey, China, Argentina and Japan had delegates faced a significant and important campaign to boycott or protest the G20 presidency. The imprisonment of women’s rights activists including Loujain al-Hathloul and the killing of Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi embassy in Turkey are examples of a Kingdom at odds with its own liberalisation – there is a tension where legislative change has outpaced social and institutional change. For the G20 and its non-government delegates, there is a dance between the productive engagement and firm hand that is required when working in a context of great contradiction.

The scrutiny of a glitzy G20 hosted under Saudi Arabia means that both the government and non-government tracks need to deliver a transparent process that delivers on its promises. Already this year we have seen this challenged.

In the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, it was not until April that women were mentioned in official communication from the government track of the G20. This is despite the overwhelmingly disproportionate economic impact of the crisis on women. Given that Saudi Arabia had promised the mainstreaming of women and the economy across the G20, once a real crisis hit, women were forgotten. This raised concerns among analysts that the W20 was simply a tool in Saudi Arabia’s attempt to “gender wash” the G20.

The Australian W20 delegation raised our concerns privately and were responded to in a manner considered satifactory. I have reservations about singling out one country alone. Across G20 member countries, there is only one female head of government (Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel). Perhaps it is a deeper structural problem that women do not have a place at the decision-making table among the world’s most important economies. This includes Australia.

The final product of the G20, the Leaders’ Communiqué, is due to be released at the Leaders’ Summit at the end of November. It relies on consensus of all member countries. While judgement might be placed on Saudi Arabia for its content and whether consensus is reached, it is worth turning to other challenges that may impact the result of the G20 this year.

The US presidential election outcome is already proving that between now and inauguration, US leadership will be unpredictable. Whether the United States, which has retreated from strengthening global institutions over the last four years, will have a representative is fair to question. President Trump has a preference for a strengthened and broadened G7 rather than a G20. This also might explain some of Australia’s incremental retreat from engagement with the G20 over the last few years.

There is more to add than the unpredictability of the remaining months of Trump’s presidency. The increasing trade tension between Australia and China may influence consensus – indeed, it would not be unheard of for disagreement to get in the way of a final joint statement (such as APEC 2018). The number of Covid-19 cases among G20 countries is enormous, with the top five highest-incidence countries all in the G20 (United States, India, Brazil, France and Russia). The tension among countries between the urgency of a health response and an economic response will certainly influence how and what the G20 leaders will be willing to endorse.

All of this points to a potentially weakened multilateral forum, rather than a functional one, lacking the capability to address a global crisis when needed. If such is the case at the conclusion of the 2020 Leaders’ Summit, it raises the question: for what and why does the G20 continue to exist?