The decades-old dispute between Russia and Japan over the status of the Kuril Islands is far from over. Tokyo, which refers to the islands as the Northern Territories, still insists on a peace treaty with Moscow that would result in Russia’s return of at least two out of four islands to Japan, while the Kremlin keeps militarising the disputed territory.

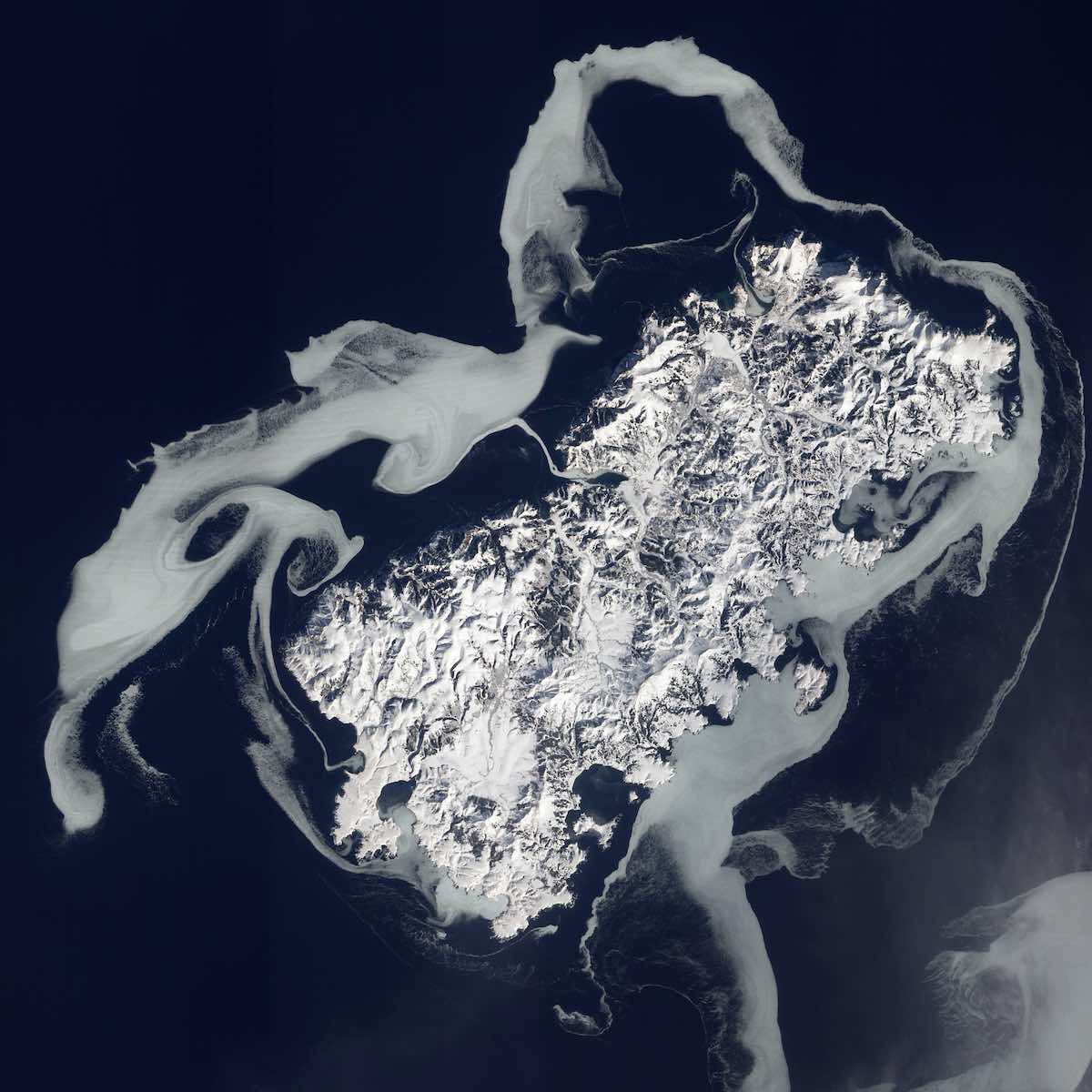

The chain of islands – stretching between the Japanese island of Hokkaido at the southern end and the Russian Kamchatka Peninsula in the north – was conquered by the Soviet Union at the end of the Second World War. Ever since, Moscow has considered the Kuril Islands an integral part of Russia. Japan thinks otherwise.

The four islands are variously known in Russia and Japan as either Shikotan, Habomai Islets/Khabomai, Kunashiri/Kunashir and Etorofu/Iturup. In 1956, the Soviet Union and Japan signed a joint declaration providing for the end of the state of war, and for restoration of diplomatic relations between USSR and Japan. The document also included a transfer of Habomai and Shikotan to Japan. But a dispute has lingered with no formal peace treaty between the two nations. Russia is the successor state of the Soviet Union, and it leaders have said on several occasions that they were ready to have territorial talks with Japan on the basis of the joint declaration.

The most recent talks between Russia and Japan over the status of the islands were held in early 2019. Japan’s then prime minister Shinzo Abe and Russian President Vladimir Putin had agreed to accelerate negotiations based on the 1956 document, which stated that the Habomai islets and Shikotan would be handed back to Japan, and the question of Kunashiri and Etorofu was to be settled during negotiations for a peace treaty.

Indications that the Kremlin was willing to discuss the status of Habomai islets and Shikotan was seen by some Russian nationalists as a treason, particularly in Sakhalin Oblast, the region which comprises the island of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands. Recent constitutional changes in Russia suggest this view has only hardened. Even though the two islands represent only 7% of the land in question, the new Russian constitution enacted in July this year includes a ban on “any alienation of Russian territories”. This would seem to preclude the return of even one square metre of Russian territory to Japan.

Japanese leaders, on the other hand, claim that the Russian Federation, as the legal successor to the Soviet Union, is obliged to scrupulously observe all of past obligations, including the unfulfilled subparagraph on the territorial issue. Japan’s Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga recently said Tokyo plans to finalise the talks on the dispute.

“We need to achieve closure in the talks on the Northern Territories, instead of postponing it for future generations,” Suga said, and pointed out that he will strive for “comprehensive development of relations with Russia, including the signing of a peace agreement”.

A potential return of the Kuril Islands to Japan would be interpreted as a clear sign of Russian weakness, which means that Moscow could also face strong pressure from the West to return Crimea to Ukraine.

All this ambition seems likely to go unfulfilled. And such a conclusion doesn’t only spring from more than 60 years of diplomatic stalemate, but also the stubborn facts of control on the ground.

Russian troops periodically conduct military drills on the disputed islands and may indeed go further. The Kremlin reportedly plans to deploy T-72B3 battle tanks to the Kuril Islands, where they can be used to destroy enemy assault forces and small enemy ships. In October, Russia deployed S-300V4 air defence missile systems to the territory for the first time to conduct military exercises. Although no one really expects Japan would invade the islands, Moscow clearly wants to make a show it does not intend to hand them over, either. With thousands of US troops already stationed in Japan, it’s not beyond some Russian analysts to speculate that Washington could establish naval bases in the Kuril Islands once Moscow and Tokyo resolve their territorial dispute.

Plus there is the potential wealth. The islands are surrounded by rich fishing grounds and are thought to have offshore reserves of oil and gas – although the value of such hydrocarbon claims are speculative. In addition, rare rhenium deposits have been found near the Kudriavy volcano on Etorofu.

Finally, a potential return of the Kuril Islands to Japan would be interpreted as a clear sign of Russian weakness, which means that Moscow could also face strong pressure from the West to return Crimea to Ukraine. Such a process would not only mean Russian humiliation in the global arena, but could also result in a serious political crisis that could lead to a breakup of the Russian Federation.

The prospective blow to Russian prestige therefore makes the territory is too important for the Kremlin to hand it over to Japan.