On 4 January 2012, at the beginning of what was commonly assumed to be Myanmar’s transition to democracy, the government-run New Light of Myanmar published an editorial that contrasted “the violent conflicts, protests and bloodshed” that mark other countries’ transitions to democracy with Myanmar’s “rapid, peaceful transition with mutual understanding and trust and negotiations as directed by its former rulers”. The military-backed government promised the people a carefully managed transition that would avoid the kind of carnage that followed the Arab Spring.

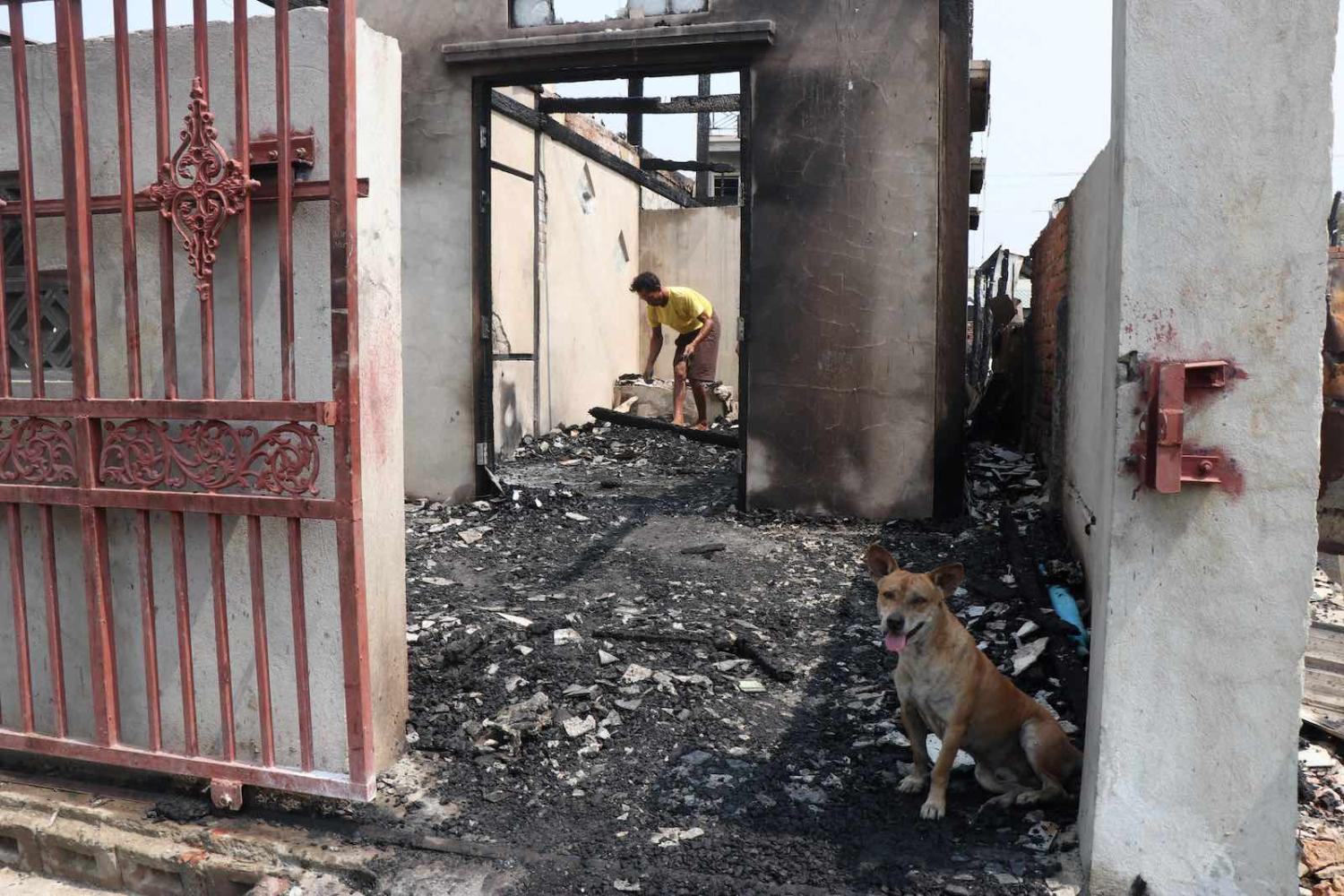

The coup d’état of 1 February 2021 left the military’s promises for peaceful transition in ruins. In towns and villages across Myanmar, those opposing the coup no longer talk about “protests” – they talk about “revolution.” A return to the status quo, which was an uneasy power-sharing relationship between the military and the National League for Democracy (NLD), is unthinkable. New and unpredictable actors have entered the stage – the armed ethnic organisations which have long been opposed to the military but which, historically at least, have also shown little affection for Aung San Suu Kyi. The tragic precedents of Iraq and Libya are on many observer’s minds.

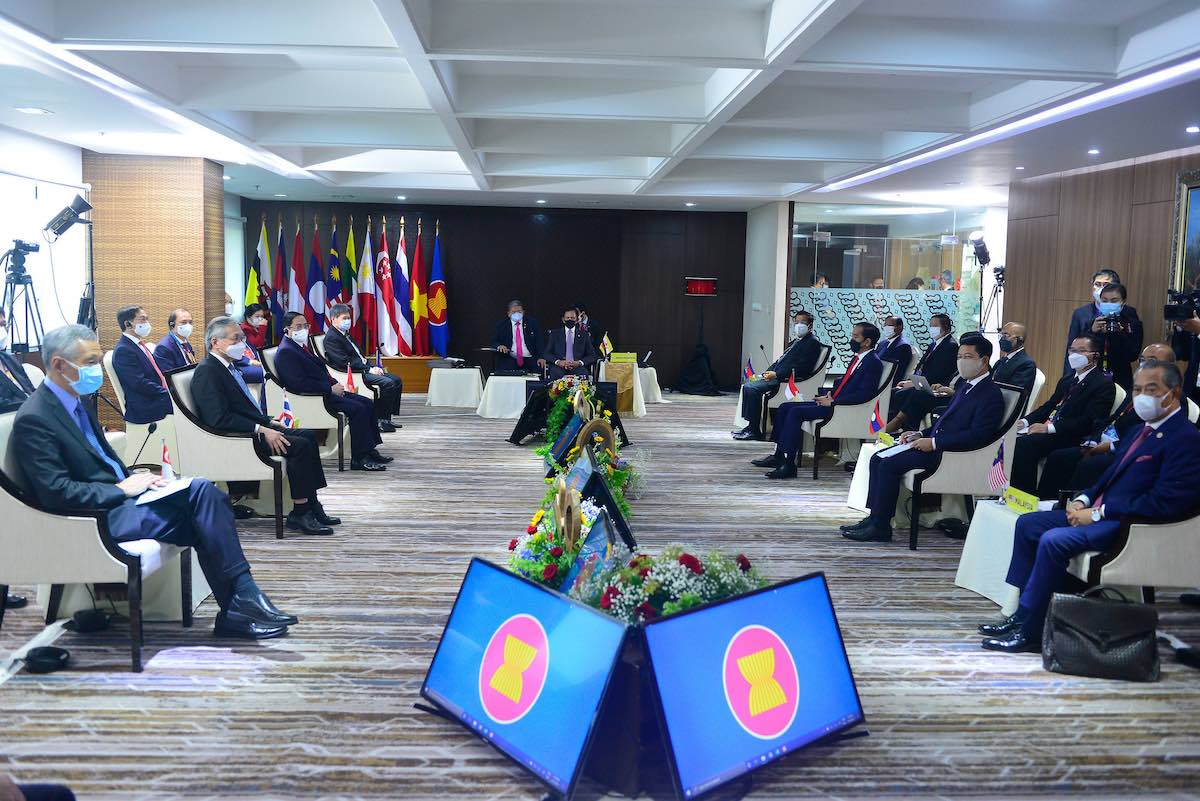

Enter the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. The five-point consensus, agreed to by coup leader General Min Aung Hlaing at the ASEAN leaders’ summit on 24 April, calls for the immediate cessation of violence, constructive dialogue, mediation, humanitarian assistance by ASEAN and an ASEAN delegation to visit Myanmar to meet with all parties concerned. The consensus is entirely in keeping with ASEAN’s traditional response to political crises. There is no attempt to shame Min Aung Hlaing or to signal moral outrage to gain the approval of Western observers. There is no promise of things that cannot be delivered, such as a reversal of the coup and a reinstatement of the results of the November 2020 election.

The consensus is pragmatic, constructive and deliberate. What it does promise is a means of achieving what the military has always said is its aim: a path towards democracy that avoids chaos and carnage. If all sides keep their promises and if ASEAN acts quickly to put the consensus into effect, it might even work. But a number of things could cause the consensus to unravel.

First, the consensus is a far cry from what protesters are demanding. The National Unity Government (NUG), which includes representatives elected in the November 2020 elections and members of ethnic organisations, is demanding the reinstatement of those election results and the release of all political prisoners – including Aung San Suu Kyi. The NUG currently insists these demands are not negotiable. If the NUG maintains this position it is difficult to see how progress can be made.

On 1 February 2021 Aung San Suu Kyi’s decades-long reluctance to compromise and her mistrust of the military were vindicated. She will be very slow to compromise again.

Second, the current alliance between armed ethnic organisations (EAOs) and the National League for Democracy is unstable. Several of the armed organisations, such as the Kachin Independence Army, have been at war with the military since transition began in 2011. Others, such as the Karen National Liberation Army, signed peace agreements with the military at around the same time. Post-transition, there has been little opportunity to establish trust between EAOs and the NLD. There are deep historical reasons for distrust.

Third, the accountability question looms large in the minds both of protesters and the military. There are currently proceedings against Myanmar in the International Court of Justice relating to the military’s treatment of the Rohingya in 2017. There is also an investigation underway in the International Criminal Court, which could encompass the military’s conduct towards protesters following the coup d’état. Prosecution before an international tribunal is utterly unacceptable to Min Aung Hlaing. Impunity is utterly unacceptable to protesters.

Finally, there is Aung San Suu Kyi. From 1990 until 2011, Aung San Suu Kyi opposed military rule and maintained her demand that the results of the 1990 elections be reinstated. Finally, and reluctantly, Aung San Suu Kyi agreed to an uneasy peace-sharing relationship with the military. On 1 February 2021 her decades-long reluctance to compromise and her mistrust of the military were vindicated. She will be very slow to compromise again. And the people of Myanmar, as ever, will be guided by “Mother Suu”.

Despite the possible pitfalls, the consensus is a notable diplomatic success for ASEAN. If ASEAN can negotiate these problems and pull Myanmar back from the brink of catastrophe, it will have achieved an extraordinary feat. Since joining ASEAN in 1997, Myanmar has been ASEAN’s errant adolescent child: wayward, obstinate, immune to influence or censure, and something of a blight on the reputation of the family. Nonetheless, ASEAN has persisted in keeping Myanmar part of the “ASEAN family”, believing that only with Myanmar inside the family can ASEAN use its moral influence to persuade Myanmar’s leaders to govern with decency.

All ASEAN countries have struggled to resolve historical issues of authoritarianism, the role of the military within the state, the reconciliation of restless ethnic minorities, and the management of development and democracy. The lesson learnt by ASEAN is that the source of liberalisation and democratisation is indigenous, and that external pressure is at best irrelevant and at worst counterproductive. ASEAN is hoping – and the world is hoping with it – that its best diplomatic efforts can pull Myanmar back from the brink.