On Friday, Indonesian officials announced that they had renamed the waters northeast of the Natuna Islands, at the far southern end of the South China Sea, the 'North Natuna Sea'. Indonesian officials were quick to emphasise that they were not renaming the entire South China Sea, only the part that falls under their claimed exclusive economic zone.

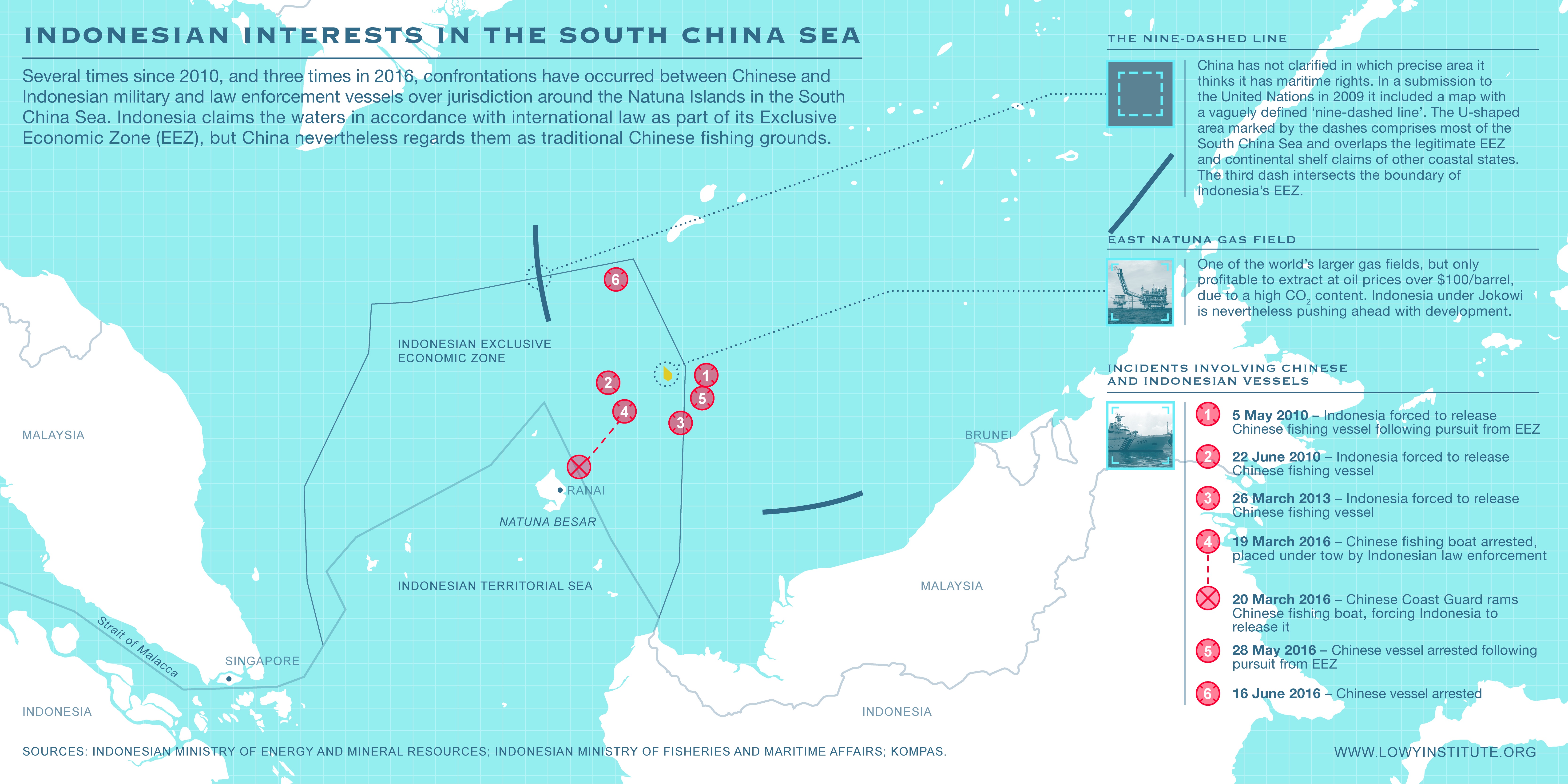

That exclusive economic zone (EEZ), however, overlaps with China's infamous nine-dash line. As the map below indicates, there have been a number of incidents in recent years in which Indonesian fisheries enforcement or navy vessels have sought to arrest Chinese trawlers in the area of the overlap. In each of these incidents, Chinese Coast Guard vessels intervened in or protested the seizures of the vessels and the arrest of their crews (earlier this year, there was a similar incident involving Vietnamese vessels).

Indonesia under Jokowi has taken action to shore up its military and law enforcement capacity in the area, and Jokowi himself has made two high-profile trips to the military base at Ranai on Natuna Besar to demonstrate his interest in defending Indonesian sovereignty over the islands and Indonesian rights to the resources in the adjacent EEZ. At the time, some analysts took these moves (and may now take Friday's announcement) as an indication that Indonesia is adopting a tougher approach to South China Sea issues.

But as I argued in a Lowy Institute Analysis last December, these moves indicate a tougher posture only on Indonesia's narrow territorial and economic interests around Natuna and not on the broader issue of Chinese activities in the rest of the South China Sea, where its violations of international law are more egregious. Indonesia is unlikely to take a leadership role in pushing back on these activities, both because Jokowi has little interest in the mantle of diplomatic leadership that his predecessor Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono coveted, and because Jokowi believes that it will be more difficult to attract Chinese capital for his signature infrastructure projects if Indonesia were to speak out.

After Indonesia announced the new name, Chinese officials' response left little doubt as to the dim view they take of the prospect of Jakarta taking a renewed interest in the subj'ect. 'Some countries' so-called renaming is meaningless,' Foreign Ministry Spokesman Geng Shuang said. 'We hope the relevant country can meet China halfway and properly maintain the present good situation in the South China Sea region, which has not come easily.'

Jokowi and his advisors believe that by going it alone on the South China Sea, they can protect their interests without damaging investment prospects. Such an approach may safeguard Indonesian sovereignty and maritime rights in the short term, as I have argued here, but it seems unlikely to prove a reliable deterrent in the long term, as the size and capability of the People's Liberation Army Navy and the Chinese Coast Guard grow relative to Indonesia's much smaller fleets. Moreover, these steps will do little to address Beijing's increasingly aggressive behaviour, disregard for international law, and refusal to negotiate in good faith on an issue of critical concern to the region, which portends poorly for Beijing's conduct in other areas as it becomes more powerful.

The Jokowi Administration is not the first Southeast Asian government to use name changes to obscure adverse developments on the water in the South China Sea. The Philippines adopted the name 'West Philippine Sea' in 2012. In Vietnamese, it has long been known as the East Sea. Even Chinese use a different term, the 'South Sea'. It was Portuguese explorers in the 16th century that added 'China'. Prior to colonisation, the waters were known by peoples throughout the region as the Sea of Cham, after the Champa society that existed on the southern shores of present-day Vietnam for much of the last two millennia. Perhaps a return to that moniker would be the most appropriate.

But rather than engaging in name games, Indonesia and other Southeast Asian states would be better off focusing on practical measures (such as organising opposition in diplomatic fora to Chinese actions that violate international law) to ensure the sea remains peaceful and free of Chinese coercion. Nevertheless, foreign observers should not interpret the latest changes in nomenclature as a sign that Indonesia is likely to do so.