The waters off Mozambique are becoming a major new security hotspot in the Indian Ocean. An Islamist insurrection in northern Mozambique that the government seems powerless to suppress has also increasingly led to disruption in the Mozambique Channel, a key global shipping route. The Quad countries and European partners must help contain the problem before other actors step into a regional vacuum.

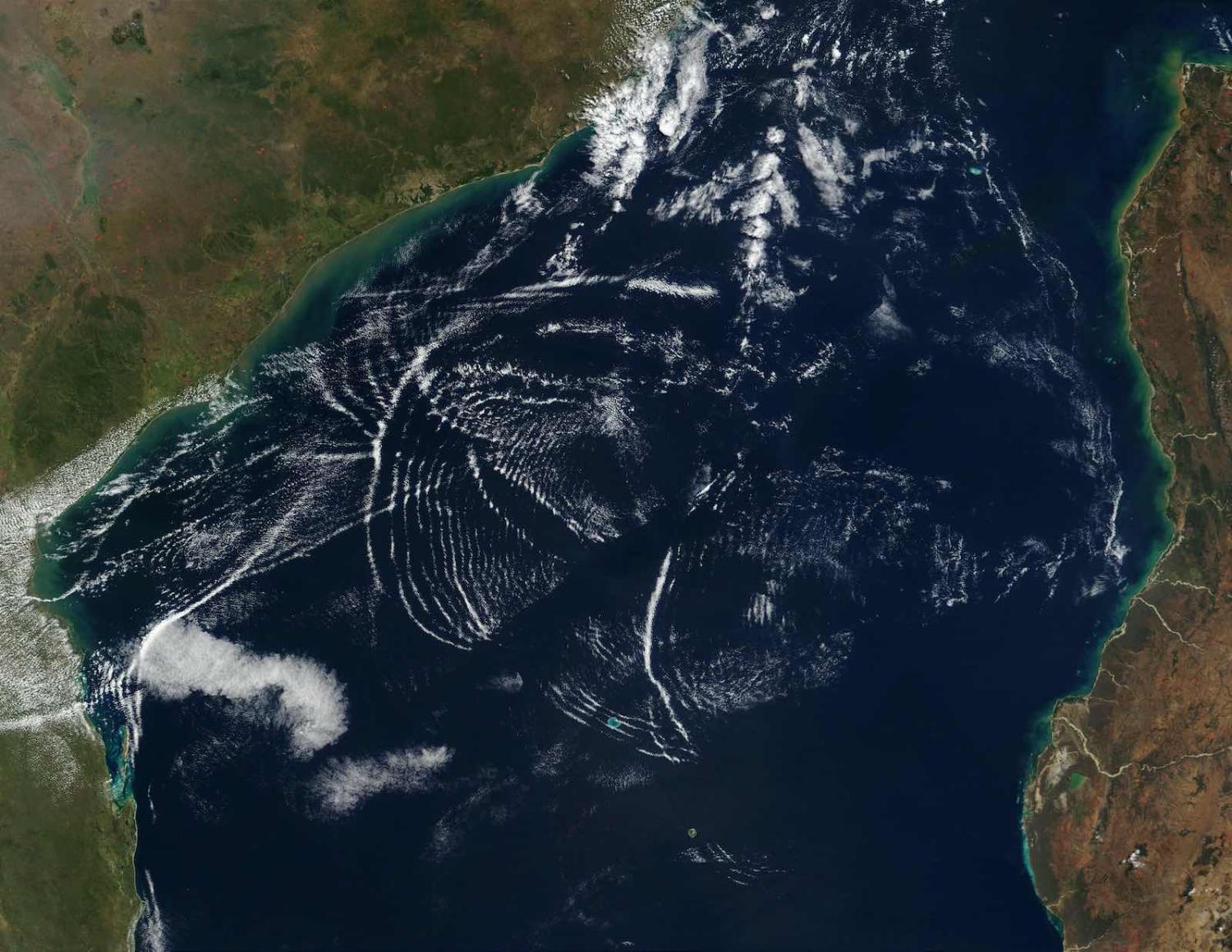

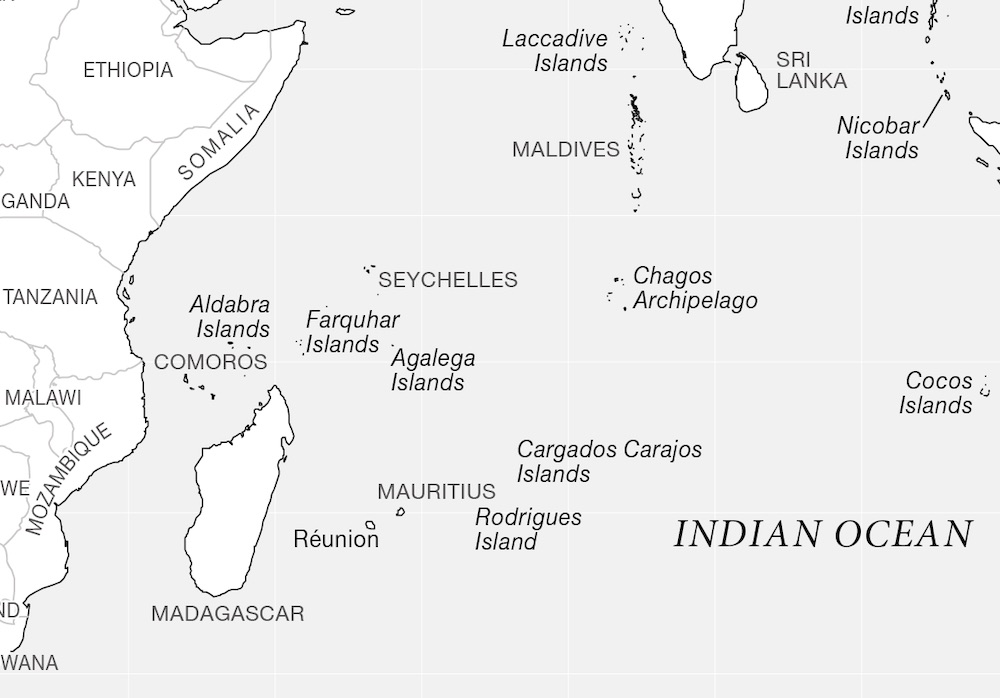

The insurgency in Mozambique has the potential to destabilise Southern Africa and embolden Islamists throughout the region. It threatens security in the Mozambique Channel, the 1800 kilometre long waterway between Madagascar and East Africa that carries some 30% of global tanker traffic. It is also the location of some of the world’s largest gas reserves.

The insurgency was started in 2017 by groups drawn from Muslim communities on the so-called “Swahili coast”. This has now included more than 800 separate attacks across northern Mozambique, resulting in at least 2600 deaths and more than 600,000 people displaced. A report from the UN Secretary-General to the Security Council also pointed to transnational links, with Somali-based Islamists in Puntland acting as a “command centre” for Mozambique insurgents. However, other analysts discount close operational links with Islamic State.

Armed clashes escalated sharply in 2020, with attacks spilling over the border into Tanzania, where the government faces local Islamist extremists. There are also growing attacks on maritime infrastructure. In August, insurgents seized a key port in northern Mozambique from government forces, raising concerns that this is a first step in insurgents venturing into piracy, as occurred in the Horn of Africa.

Maritime drug smuggling is a key source of funds for insurgents. The so-called “Smack Track” has long brought heroin grown in Afghanistan down the East African coast, where a substantial portion is now landed in northern Mozambique before being transported to Europe and elsewhere. Heroin is also increasingly supplemented by crystal meth, produced in Afghanistan from local shrubs.

Another big factor is the development of a major offshore gas industry in the Mozambique Channel off northern Mozambique. This involves planned investments of some US$50 billion to extract an estimated 100 trillion cubic feet of gas, including a major onshore gas liquification plant. France’s Total and US-based ExxonMobil are major investors. In January 2021, following a series of escalating attacks, Total began to move part of its logistical operations from northern Mozambique to safety on the French-administered island of Mayotte in the Channel.

The Mozambique government, which is in severe debt distress, is unable to take effective action against the insurgency, and has increasingly relied on mercenaries. But it has been somewhat reluctant to accept international assistance.

Russia has tried to promote itself as a partner, eyeing a share of Mozambique’s offshore gas reserves for Gazprom and Rosneft. Moscow uses private security contractors as its proxies in many countries in Africa. In September 2019, up to 200 mercenaries from the Russian Wagner group were deployed to Mozambique with equipment and logistical support from the Russian Air Force and, possibly, also the Russian Navy. But the contractors suffered heavy casualties and were withdrawn from operations within months.

The Quad and like-minded partners have important interests in stopping the insurgency spilling further across Mozambique’s borders or into the maritime domain.

France and other European partners are now stepping up efforts to contain the problem. France is historically a leading maritime security provider in the southwest Indian Ocean, with two French frigates and patrol boats based in French Reunion. But France lacks maritime patrol aircraft based in the region.

Portugal, the former colonial power in Mozambique, has agreed to send a training mission of more than 1400 troops. Lisbon is also using its current Presidency of the European Union to lobby for the deployment of an EU military mission. Spain has also offered military support.

The United States is also finalising an offer of counter-terrorism assistance.

The South African Navy has conducted intermittent anti-piracy patrols in the Mozambique Channel since 2011, and is now establishing a new forward operating base at Richards Bay in South Africa’s north in response to the insurgency. South Africa and its Southern African Development Community (SADC) partners have offered naval and intelligence support. But Mozambique appears reluctant to involve African partners.

India has also long positioned itself as a net security provider in the south-west Indian Ocean and as a security partner to Mozambique. Since 2020, Indian Navy P8I maritime patrol aircraft, staging through Réunion, have conducted joint patrols with the French Navy in the Mozambique Channel. India is also in the process of constructing an air and naval facility on Mauritius’ remote Agalega island, near the north end of the Channel, improving its ability to cover the region.

Australia will be wary of any new defence commitments in the western Indian Ocean. The Royal Australian Navy has been deployed there for years, interdicting smugglers on the Smack Track. But that presence is being reduced, following an increased focus on areas closer to home, including the Pacific. Australia may need to consider what non-military assistance it can provide.

The Quad and like-minded partners have important interests in stopping the insurgency spilling further across Mozambique’s borders or into the maritime domain. A decade ago, Somali-based piracy was the trigger for the international militarisation of the waters off the Horn of Africa. There are good reasons to avoid a similar dynamic in southern Africa.

The crisis should also be seen an opportunity for countries such as France and India to demonstrate their value as security partners in the region. It may also be an opportunity to build cooperation with South Africa, which is increasingly a “swing state” in geopolitical competition. Failure to contain the conflict will leave a vacuum for other actors to fill.

This article is part of a two-year project being undertaken by the ANU National Security College on the Indian Ocean, with the support of the Australian Department of Defence.