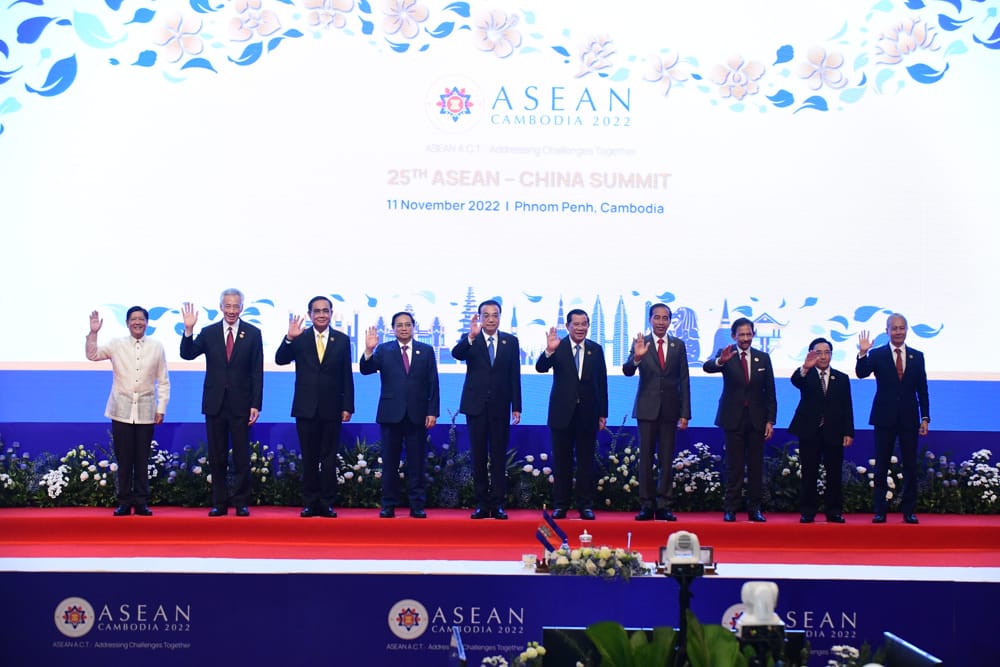

As regional leaders gathered for the ASEAN summit in Cambodia last week, a sideline meeting also took place with China. For all the talk about regional rivalries amid growing geopolitical tensions, when the leaders gathered at the table, food security was a topic of significant concern.

Green beans, cassava, mangosteen, palm oil, animal feed, garlic, pears, ginseng gelatin, pineapple, banana, salak, porang, swallow’s nest. These commonplace goods might not dominate headlines in the way submarine deployments or hypersonic missile developments do, but reliable food supplies are critical, particularly for Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest country.

In August this year, the total of Indonesia’s palm oil and related products exports to China reached US$3.6 billion, making Indonesia the largest palm oil exporter to China for seven years running. Meanwhile, the export value of Indonesia’s fishery products to China reached almost US$500 million for the first half of this year.

At the ASEAN-China summit, Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo, commonly known as Jokowi, emphasised that “regional food security is a main priority”, underscoring the fact that the combined population of ASEAN and China – more than two billion people – faces a difficult task to ensure food availability and affordability. Jokowi said: “I hope ASEAN and China will collaborate on ensuring food reserves and the food emergency mechanism in the region, developing food production in the region, and investing in agricultural innovations.”

China and ASEAN countries also pledged to increase food productivity by expanding cooperation on producing rice, soybean, corn and other crops and by ensuring the reliable supply of meats, vegetables, fruits and aquatic products.

Efforts to enhance regional food security have gathered pace in recent times. Earlier this year, Indonesia and China signed a Memorandum of Understanding on the digital economy, with a focus, among others, on the transfer of technology to increase food reserves. The MoU strengthens previous signed agreements, such as the Nanning Joint Statement of the 5th China-ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (SPS Cooperation), which aims to facilitate the trade flow in agricultural products between the two countries. Food security was also the main topic discussed during Jokowi’s visit to Beijing in July and was brought up by Indonesia during foreign ministers talks with ASEAN and China in August.

Some of this effort is driven by the private sector. In June, for example, PT Rajawali Nusantara Indonesia (Persero), known as ID Food, in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture, announced plans to export rice and other agricultural products to China. Indonesia also promoted its agricultural products this month at the China International Import Expo in Shanghai. As many as 49 Indonesian firms, mostly small and medium enterprises, also participated in the exhibition, which was attended by 145 countries.

Food security has been one of the major concerns of Xi Jinping. With one-fifth of the world’s population, yet only nine per cent of global arable land, China is working hard to ensure stable food supplies. On several occasions, Xi has called on the country to be aware of the issue. Food security also featured in China’s latest Five-Year Plan (2021-2025), announced at the recent Communist Party Congress.

ASEAN is considered by China to be a crucial source of imported food and agricultural products, with Indonesia a special focus. China Daily published an article in August this year arguing that: “Indonesia can lead efforts by the ASEAN grouping to bolster global food security [and] Indonesia’s role is significant not only for the region but also for the world’s developing economies.”

China’s view of Indonesia as a major contributor to its food security is exemplified by reports that several Chinese state-owned enterprises have approached Indonesia’s Ministry of Agriculture to increase its rice exports to China from 100,000 tons each year to 2.4 million tons.

Interest, however, is not only one-way. Indonesia, which has been working to increase its agricultural exports, views China as a prime market. It was reported that despite an annual eight per cent growth in its agricultural exports to China, Indonesian products make up only four per cent of total agricultural imports in China. Indonesia also sees China as a gateway to expand into wider East Asia, including Japan and South Korea.

At the same time, Indonesia has its own food security concerns. Besides the rising food and energy prices caused by global tensions including the war in Ukraine, Indonesia has been relying on several food imports to meet its domestic needs.

With shared concerns, it is likely that food will become the foundation of future China-Indonesia ties. The two countries will need to ensure that ongoing territorial disputes, which include the issue of illegal fishing, are managed carefully in order not to disrupt economic cooperation. While ignoring such issues may work for now, as was the case during the recent ASEAN-China summit, these disputes are set to cause deeper problems for cooperation in the future.

Main photo via Flickr user Theo Crazzolara