On behalf of my Chairman Sir Frank Lowy as well as the Board and staff of the Lowy Institute, I would like to express my sadness at the news that our friend, colleague and mentor Owen Harries passed away yesterday.

When Owen joined the Lowy Institute as a Nonresident Fellow shortly after its establishment in 2003, he was already an esteemed elder statesman of the foreign policy world. In Australia he had been an academic, a trusted adviser to Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser and served as ambassador to UNESCO. He had also spent nearly two decades on the great stage of Washington, DC, as the founding editor of The National Interest. You can read about Owen’s influence on the American debate, and a generation of scholars, in Jacob Heilbrunn’s fine tribute in The Interpreter.

For those of us who were starting our careers at the Lowy Institute in the early 2000s, it was our good fortune that Owen and his wife Dorothy had decided to retire to Sydney. Harries influenced me in several ways. Although I am too much of a romantic to be a foreign-policy realist, I was hugely impressed by the realism of his views at a time of American hubris. In particular, I agreed with Owen’s statement in his brilliant 2003 Boyer Lectures that the appropriate Australian response to the US request for us to join in the 2003 invasion of Iraq would have been “restraint, some deep reflection and a request for clarification, rather than eager and unqualified support”.

If you’re going swimming, Owen often reminded me, swim in the deep water, not the shallows.

An alliance is a serious matter, but it does not require us to support our ally when that ally is in the wrong. The Iraq war made the United States weaker, poorer, less respected and less feared, and Australia was wrong to go along with it.

The same principles that informed Owen’s foreign-policy thinking – self-control, discrimination and understatement – also marked his writing style. I learned from this too. Less is more.

Finally, I admired his ambition. This Welsh-born Australian had the imagination and chutzpah to believe he could influence the international relations of the most powerful country in history. His life is yet more proof that the qualities of the immigrant are highly correlated with the qualities of the entrepreneur.

Owen always encouraged me to address big, central issues in my writing rather than small, marginal ones. If you’re going swimming, he often reminded me, swim in the deep water, not the shallows.

When I was appointed Executive Director of the Institute, I was delighted to recommend to the Board that we inaugurate the annual Owen Harries Lecture on the practice of geopolitics. The Harries Lecture has now been given by important figures such as Kurt Campbell, Stephen Hadley and Nicholas Burns.

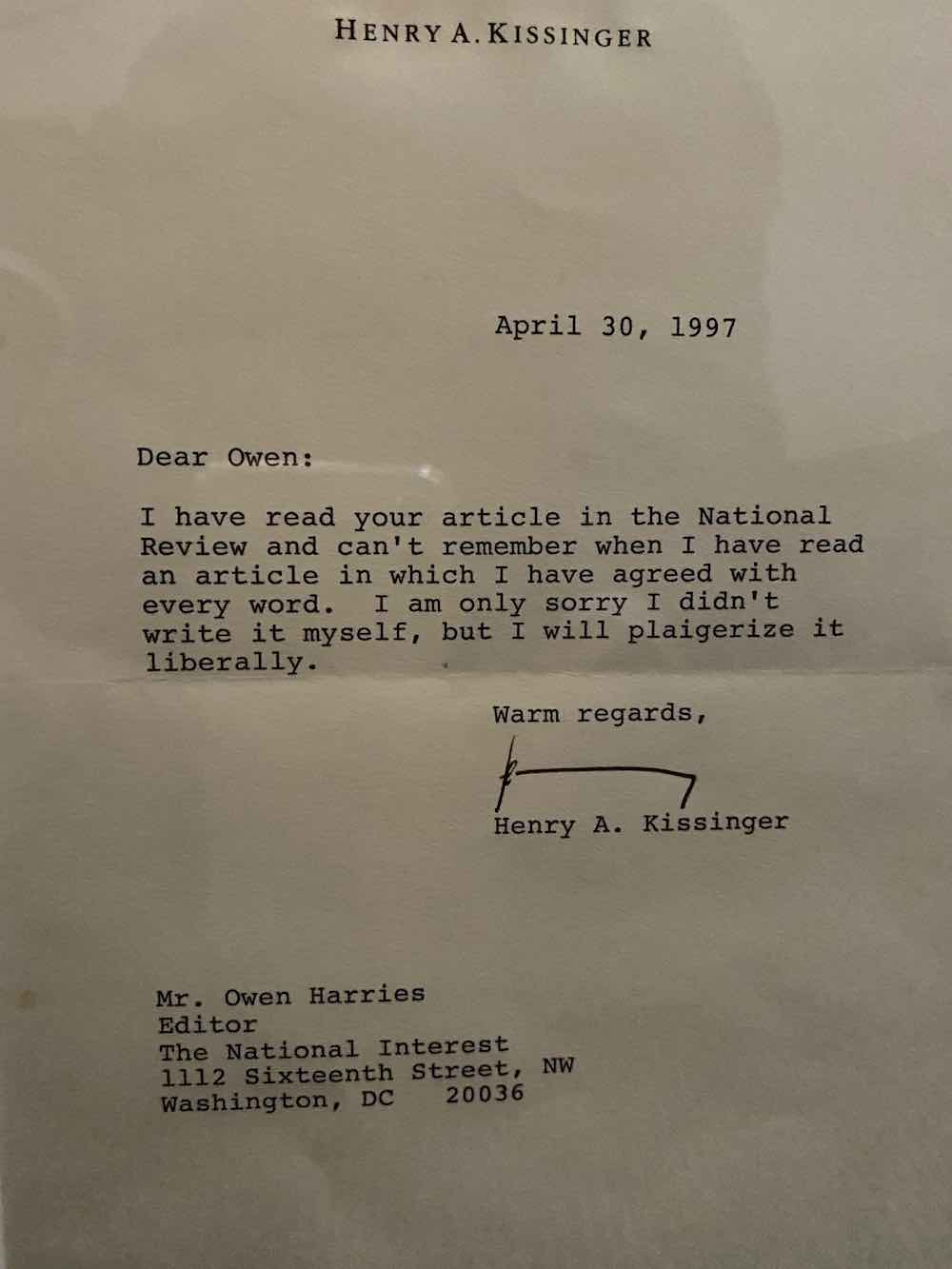

A few years ago, Owen donated to the Lowy Institute two letters of congratulation he had received from foreign-policy luminaries. We display them both in our headquarters at 31 Bligh Street. The first was from the father of containment, George F. Kennan. The second was a charming letter dated 30 April 1997 from the most famous realist of all, Henry Kissinger. “I have read your article in the National Review and can’t remember when I have read an article in which I have agreed with every word,” wrote Kissinger. “I am only sorry I didn’t write it myself, but I will plagiarise it liberally.”

Vale Owen Harries.