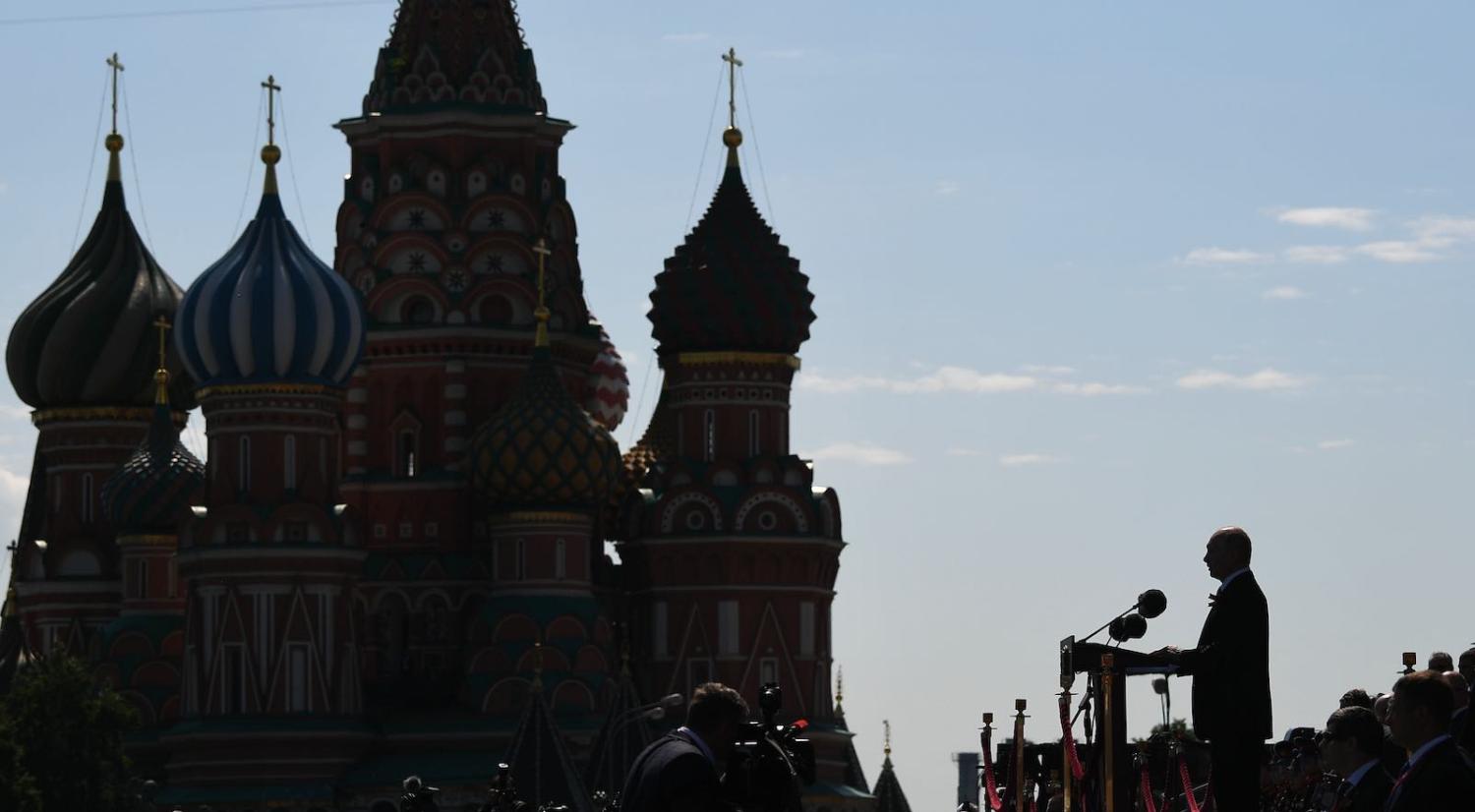

Vladimir Putin, who rose to power more than 20 years ago as symbol of youth, strength and vitality, is today confronting an uncomfortable truth. In short, his previously rock-solid regime is starting to look a bit tired.

The Russian government’s recent violent crackdowns against protesters across the nation trod a well-worn path. They signalled that the Kremlin is no longer prepared to let the public blow off steam against rampant government corruption, or against the detention of government critic Alexey Navalny, who was immediately arrested upon returning to Russia, having recovered from an attempt to kill him with a military-grade chemical weapon in 2020.

This is not to say that the Russian government is under immediate threat. It has seen what has happened in Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan and Belarus, and it has put considerable resources into protecting itself against “colour” revolutions spreading to Russia. Its use of disinformation, black PR, proxy violence, cyber attacks and dominance of public narratives are a reminder that the weapons Putin has turned against others – in Crimea, Ukraine, the Baltics, the UK and the US – have long been refined against his own people.

This time Putin’s enemies are inside Russia’s gates and not just bashing against them.

Yet Putin’s leadership looks old because it increasingly is old, especially in a nation where life expectancy for males – which dominate the political classes – is just 66.

Putin himself is approaching his 70th birthday and has previously signalled that he would like to retire. Among his potential heirs, Nikolai Patrushev (the Secretary of Russia’s Security Council) is older than Putin. The most youthful Kremlin clan, led by the more moderate Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin and former president Dmitry Medvedev, is also probably its weakest. Putin’s foreign minister Sergei Lavrov is in his 70s and has had his requests to hand over to someone younger repeatedly denied.

The recent protests have also been dominated by young Russians, exacerbating the optics of an ageing political elite losing touch with younger generations. Having previously succeeded in depoliticising Russia’s youth, and learning from the Pussy Riot protests of 2012, the government went to significant lengths to keep young people away from the protests. It scheduled surprise exams, asked parents to forbid their children from attending and decried the “brainwashing” of young people by Navalny – himself regularly painted by state media as an idiot, a CIA stooge or an anarchist.

This gives Putin a number of new problems. He has previously faced down his challenges safe in the knowledge that he could bring the population along with him by blaming others: the US, the EU, Islamist terrorists or the decadence of woke neoliberalism.

Along the way, global narratives about Russia changed from viewing it in gradual decline to seeing it as newly emboldened and revitalised. A co-opted Trump administration muted official US criticism of the Putin regime, downgraded NATO and bought Putin a solid four years to fragment the West. He was able to use conventional levers such as gas dependencies against the European Union, and he exploited its internal divisions over Brexit, its economic malaise and the creep of the far right. The tribalisation of American politics to the point of a nascent civil war was amplified by Russian information operations. Putin doubled down on the relationship with China, receiving warm words of friendship from Xi Jinping, but at the long-term expense of dependency on Chinese investment, as well as growing PRC influence on Russia’s Central Asian flank.

But this time, Putin’s enemies are inside Russia’s gates and not just bashing against them. The biggest test yet of Putin’s monolithic authority is a mundane one: the disconnect between rhetoric and reality. Navalny’s YouTube exposé of an enormous palace on the Black Sea, which he alleged was built for Putin by corrupt oligarchs, has now been viewed by tens of millions of Russians. True or not, it seems to have convinced much of the population that the Russian rot starts at the very top.

Under Putin’s watch, Russia has also seriously bungled its response to Covid-19. Its much-hyped Sputnik V vaccine has been slow to roll out. In December, Russia revealed that it had undercounted deaths from the pandemic by two thirds, putting it behind only Brazil and the US among nations with the worst overall death toll. And as the pandemic drags on, global energy prices for oil and gas remain lower than the Kremlin needs to provide essential services, feed its massive infrastructure projects in the Far East and the Arctic, and continue to modernise the Russian military. In the longer term, as the boom in renewables continues, an undiversified Russian economy faces the prospect of becoming a seller of last resort, supplying low-profit energy to clients who cannot afford anything else.

Far from a revitalised nation, then, Putin’s Russia is starting to look like the last phases of the Brezhnev era under the Soviet Union. At some point, artificial controls, sovereign wealth spending and selective reporting will reveal an unbridgeable gap between the official line of steady growth, and the reality of everyday life.

How will Putin respond? A relaxation of internal controls is unlikely, not just because reforms are dangerous times for bad regimes, but because Putin and his team saw what happened to Mikhail Gorbachev. Internationally, and in return for a more muted Western position on its domestic tactics of repression, Putin may well offer the EU and the new Biden administration quick foreign policy wins on a range of issues, from gas to arms control.

However tempting, such a move would be dangerous and should be resisted. In essence, it asks the West to separate Russia’s internal conduct from its external behaviour. In addition to throwing Navalny under a bus, it also contradicts the core narrative liberal democracies have advocated for over two decades. Having plumped for a rules-based order where state sovereignty no longer represents a cloak for leaders to hide behind, yet another “reset” with Russia would merely be hypocritical, and potentially lengthen the lifespan of an increasingly sclerotic regime.