Whoever first said that “you should never waste a good crisis”, the Chinese government appears to be listening. At least when it comes to Hong Kong. With the city and the world’s attention on Covid-19, Hong Kong police swooped at the weekend to arrest 15 veteran activists on allegations of illegal assembly, among them 81-year-old “grandfather of democracy” Martin Lee.

The arrests earned condemnations from senior US, UK, Australian and European Union officials. But, more importantly, the raids came after a week in which the Chinese government’s revamped office in Hong Kong, given new hard-line leadership by President Xi Jinping, started to show its muscle. It called for a long-delayed national security law to be implemented urgently, and brazenly asserted its right to supervise Hong Kong affairs, unilaterally re-interpreting the city’s mini-constitution. The brief, coronavirus-assisted lull that followed the rolling mass protests and clashes with police last year is clearly over.

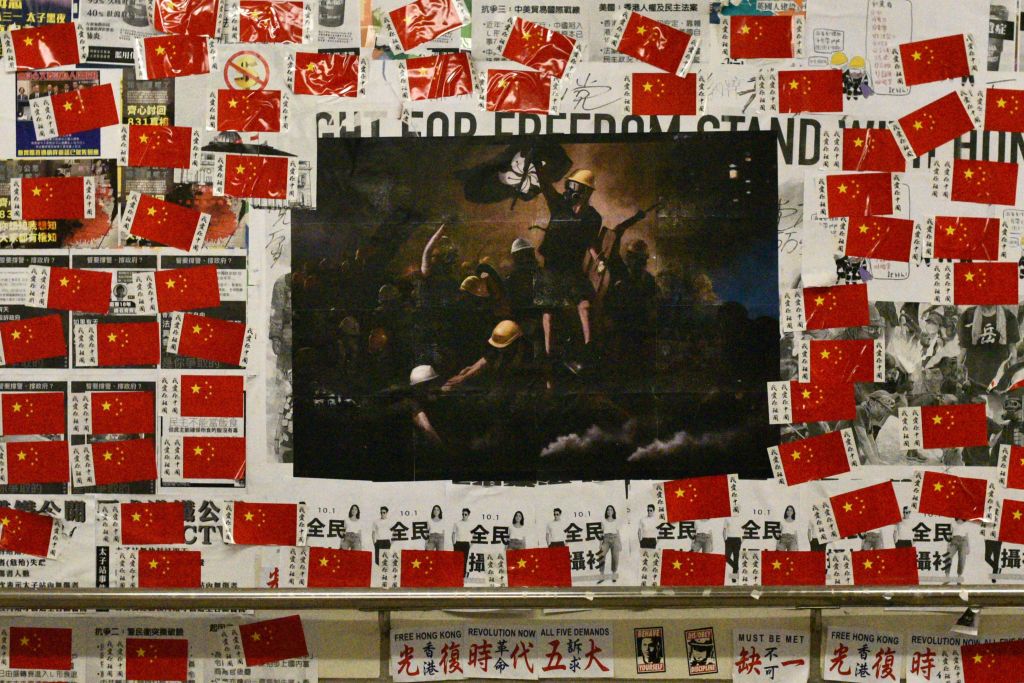

It was inevitable that Beijing would look to teach the city a lesson after the humiliations of 2019 – a year when democracy activists pushed back against the authorities with unprecedented unity, tenacity and violence on the streets, while also trouncing pro-Beijing parties in local council elections. Luo Huining, the disciplinarian new head of Beijing’s Liaison Office in Hong Kong, appears to have taken to his job with relish.

The recent arrests could foreshadow a broader crackdown on the democracy movement, to prevent it from repeating its ballot-box success in this year’s elections for the Legislative Council. But, however many democratic candidates Beijing disqualifies, the renewed crackdown is likely to deepen existing dividing lines in Hong Kong, rather than prompt any breakthroughs.

Hong Kong has been descending into a spiral of political conflict for a decade, with a rapid acceleration over the last few years. Beijing has always seen the One Country, Two Systems arrangement as a messy compromise to smooth the handover from British rule in 1997 rather than a long-term basis for political freedoms and autonomy for Hong Kong. In the last 10 years, and especially since Xi Jinping took power in 2012, it has intensified efforts to assert control over Hong Kong’s politics, economy and society.

But Beijing’s repression has prompted regular backlashes, from the 2014 Occupy movement to last year’s protests against the extradition bill. The more it squeezes, the more it forces the democratic opposition to solidify and, ultimately, push back. As the famous slogan from last year’s invasion of the Legislative Council stated: “It was you who taught us that peaceful protest doesn’t work.”

By pushing so hard, the authorities risk intensifying the very nemesis of political violence that they claim to be opposing.

The Hong Kong government, which now speaks almost as one with Beijing, has begun to accuse protesters of committing “terrorism”. Some front-liners did use violence to fight the police last year. But, while there was unease about this in the democracy camp, there was a widespread sense that the police had triggered the backlash through their own excessive use of force.

A failure to prosecute any police officers for these abuses has deepened the feeling of injustice, and the lack of trust in the authorities. Meanwhile, nearly 8,000 protesters have been arrested since last year and more than 1,000 charged, a generation of political prisoners-in-waiting for Hong Kong’s jails. By pushing so hard, the authorities risk intensifying the very nemesis of political violence that they claim to be opposing.

Ultimately, Beijing will not be deterred by criticism from foreign governments, who it has accused of “condoning evil”. But neither will it be deterred by the fact that its actions are likely to make the problem worse in the foreseeable future.

Both the Chinese Communist Party and the Hong Kong democracy movement are settling in for a long and painful struggle. Beijing seems to genuinely believe it can prevail eventually by arresting trouble-makers, closing down the space for opposition, neutralising hostile foreign forces, co-opting the business community, and indoctrinating a new generation to be loyal to the motherland.

For their part, democracy activists well understand that the current leadership in Beijing will never respect their rights, autonomy, and identity. They are, in truth, fighting a rear-guard action to disrupt the authorities while hoping to keep the flame of resistance alight until something dramatic changes in Beijing.