Diego Garcia is the United States’ major geostrategic and logistics support base in the Indian Ocean. Sovereignty over the island is increasingly being challenged by Mauritius, but it seems unlikely that Washington would be interested in a deal that would facilitate its transfer.

The base has its origins in the 1960s, as decolonisation swept over the region and Soviet influence grew in many of the newly independent countries. But it was China, not the Soviet Union, that spurred Washington to focus on acquiring a base. The policy trigger was the 1962 Sino-Indian war, when Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru had pressed Washington for military assistance to India. President John F. Kennedy dispatched the US aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk to provide air support if China drove south to Calcutta – but a ceasefire was reached before it arrived.

By 1964, a regional survey judged that Diego Garcia, an atoll in the Chagos Archipelago that was an administrative dependency of the distant British colony of Mauritius, some 1160 nautical miles (nm) of open ocean away, was best suited. It had a lagoon and land that could support an airfield and other infrastructure, and its remoteness satisfied Washington’s desire to make itself immune from the nationalist pressures of the day.

It was China’s actions in 1962 that led to the base, and it is now China’s Indian Ocean military footprint that increases its value beyond its role in supporting US military operations in the Persian Gulf region.

To insulate Diego Garcia from passing into the hands on of a non-aligned government, London detached Chagos from Mauritius’ colonial administration and created a new entity known as the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). In 1966, London agreed to make Diego Garcia available to the US for defence purposes for 50 years.

As they say in the real estate business, the three most important considerations when valuing property are location, location, and location. Diego Garcia more than satisfies the criteria. It is situated near the center of the Indian Ocean, within striking distance of virtually all maritime choke points, vital sea lines of communication, and potential Chinese naval bases in the region: Djibouti and the Bab al Mandeb (2170 nm), Strait of Hormuz (2240 nm), Gwadar, Pakistan (2030 nm), the Eight Degree Channel between India and the Maldives (895 nm), Hambantota, Sri Lanka (1550 nm), Kyaukphyu, Myanmar (2030 nm), Strait of Malacca (1770 nm), and Lombok Strait (2625 nm).

It is a perfect base for US Navy maritime patrol aircraft and especially US Air Force heavy bombers. All the locations mentioned above are within unrefueled combat range of B-1B and B-52H bombers. (B-2s, with an advertised combat range of 6000 nm, are generally deployed from the US, but have been deployed to Diego Garcia in the past.) USAF bombers and tankers have conducted combat missions in support of US combat operations throughout Southwest Asia since the 1991.

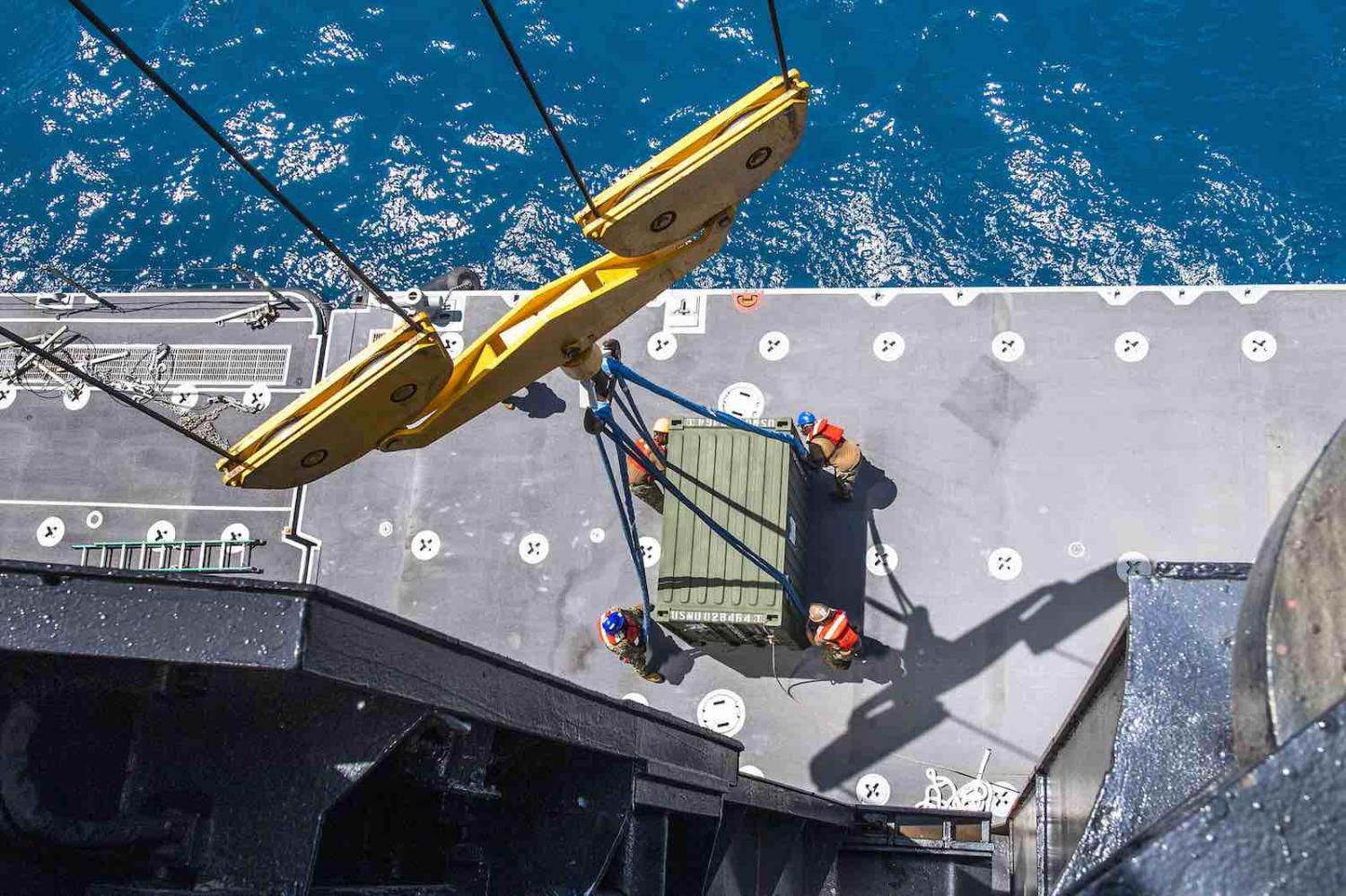

Since the mid-1980s, the base has boasted a wharf and facilities suitable for an aircraft carrier, and the lagoon provides anchorages for other warships and ships loaded with prepositioned equipment. The US Navy often stations a submarine tender and a repair and logistics ship to support deployed attack submarines.

It was China’s actions in 1962 that led to the base, and it is now China’s Indian Ocean military footprint that increases its value beyond its role in supporting US military operations in the Persian Gulf region. The PLA Navy has maintained a modest presence in the western Indian Ocean for more than 10 years, and China’s recently established base in Djibouti is judged by the US Department of Defense to be only the first of several. China’s most important sea lines of communication traverse the Indian Ocean and play a key role Beijing’s prime strategic and economic program, the Belt and Road Initiative.

But while in the 1960s Diego Garcia seemed a tidy solution to Washington’s desire for a base isolated from the uncertainties of potentially fickle newly independent states, it appears less so now.

Mauritius has long chaffed at what it considers the illegal detachment of the Chagos Archipelago. In 2019, after decades of legal manoeuvring, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) concluded that that Britain should return Chagos to Mauritius. The UN General Assembly echoed this finding, concluding that the UK’s decolonisation of Mauritius was “incomplete”, a seemingly contrived finding, and adopted a non-binding resolution that demanded the UK unconditionally withdraw its “colonial” administration with six months.

London responded that it had “no doubt as to our sovereignty over BIOT, which has been under continuous British sovereignty since 1814. Mauritius has never held sovereignty over the BIOT, and the UK does not recognize the claim”.

The Mauritius government has been relatively self-effacing in its public comments, suggesting it has no intention to demand the dismantling of the base. Officials have said that Mauritius accepts the future of the base and would be willing to enter into a long-term agreement. The fact that the US pays US$63 million annually for rights to a more modest facility in Djibouti has undoubtedly not been lost on officials in Port Louis.

A deal with Mauritius seems possible, but would Washington be interested in such an outcome? Probably not – putting sovereignty into the hands of a landlord who could order Washington overnight to vacate introduces too much uncertainty. Mauritius would have all the leverage, and could turn to at least two other possible tenants, India or China, if the US were to leave or be evicted. Washington has been silent since the UN vote in May 2019. But its silence makes the US position clear. A March 2018 statement to the ICJ contains a revealing footnote: “In 2016, there were discussions between the United Kingdom and the United States concerning the continuing importance of the joint base. Neither party gave notice to terminate (the lease agreement) and the Agreement remains in force until 2036.”

This piece is part of a two-year project being undertaken by the National Security College on the Indian Ocean, with the support of the Department of Defence.