Sovereign nation

It is 18 months since Prime Minister Scott Morrison sent Australians off to their first locked-down Easter with the somewhat mixed message that the government needed to “look carefully at our domestic economic sovereignty”.

From fixing the toilet roll crisis to a world-leading tightening of foreign investment regulation, to this year and the eclectic May budget supply chain measures, there has been a lot of activity since.

But Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s September speech, which exhorted companies to develop a “China plus” strategy, is the closest the government has come to fleshing out what all the careful looking at domestic economic sovereignty has amounted to. And that was essentially:

We have shown great resilience to date. And I am confident in our ability to withstand any shocks we may face.

As noted here previously the government has curiously not explicitly responded to the reports it has from the Productivity Commission on these issues. However, those essentially optimistic concluding comments from Frydenberg could be seen to align with the relatively benign Commission analysis of the country’s supply chain resilience, which contrasts with some more alarmist views about isolated island nation vulnerability.

This week we have two interesting new contributions to this debate in the form of two key reports. Both underline that any vulnerabilities which have come to public attention over the past year actually already existed well before the pandemic.

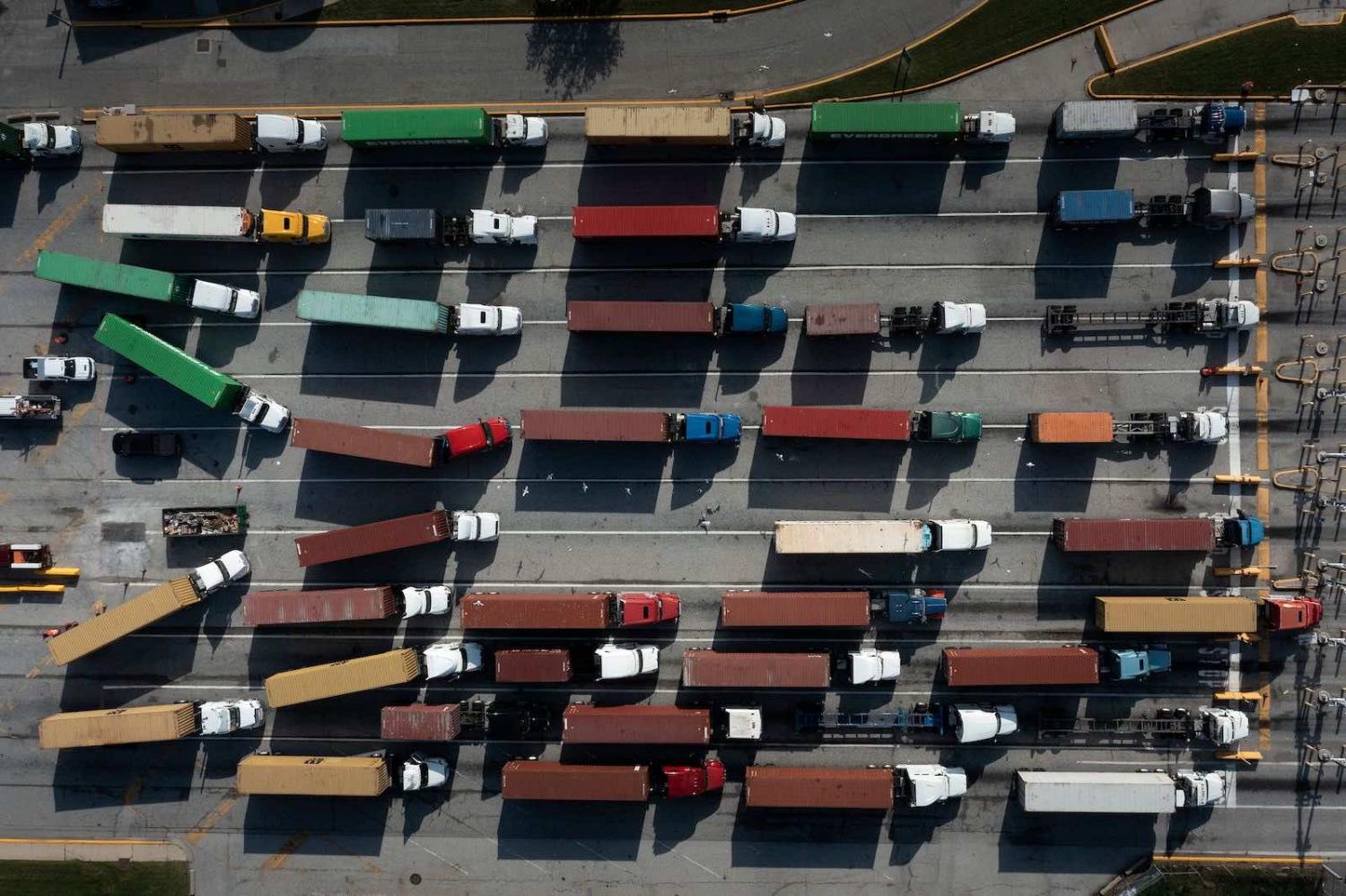

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has weighed into the global supply chain crisis in a review of container terminals in what amounts to the first official Australian analysis of a crisis that has received much more attention in countries as diverse as the United Kingdom and China. It says:

Australian importers and exporters are finding this situation particularly challenging. Many are struggling to get all their cargo on ships and are facing rapidly escalating freight rates. Some are paying significant premiums and surcharges to shipping lines to obtain priority loading, but even this does not guarantee on-time delivery.

But in a parallel to the way this debate in the United States has moved from Chinese trade malpractices to domestic logistics bottlenecks, the ACCC is arguing that the government needs to fix underlying issues that have aggravated the pandemic’s container logjam. These range from continued industrial relations problems at ports, excessive charges by monopoly privatised ports and a competition law loophole, which allows shipping companies to cooperate on price and schedule setting.

It is time for a considered government response to these issues rather than a more likely China-tinted grab bag of economic nationalist measures during an election campaign.

Meanwhile the Australia China Relations Institute and the Business Council of Australia have taken some issue with the Productivity Commission approach to supply chain vulnerability in a study which brings a new lens to the economic sovereignty debate.

It concludes that Australia’s export market concentration (essentially China) has been broadly in line with a peer group of high-income medium size economies, except for the past year with the high iron ore price. And that is now receding.

But Australia is an outlier in export product concentration obviously because of reliance on three key commodity exports in iron ore, coal and gas – but also in the emerging services sector where Australia is more dependent on tourism and education-related travel compared with the peers.

At a time when Australia’s powerful resources industry is under pressure over climate change, this study then goes on to suggest that the resources boom has had a larger “hollowing out” impact on manufacturing in Australia than the peer countries. It suggests this has had “adverse implications for overall productivity growth and income inequality” and has fostered the debate about the need for great sovereign production capacity.

It is time for a considered government response to these issues rather than a more likely China-tinted grab bag of economic nationalist measures, including building the new submarines, during an election campaign.

Dollar diplomacy

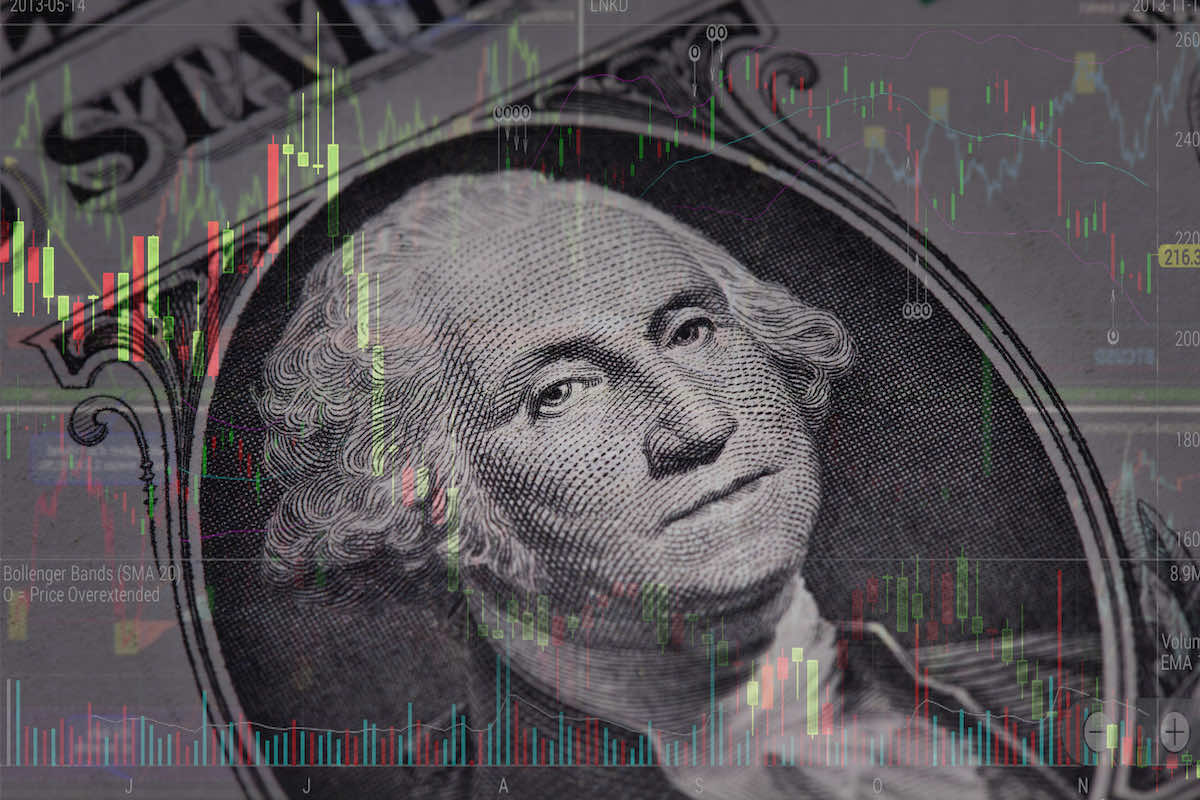

As Australia’s effort to consider a Magnitsky-style law for human rights abusers winds its way through the parliamentary processes, the US Treasury has cautiously called a sort of timeout on the escalating use of economic sanctions as a diplomatic tool.

In August, Foreign Minister Marise Payne announced some changes to Australia’s existing sanctions framework and a review to decide whether a Magnitsky law that allowed more specific targeting of perpetrators was needed. She noted that: “the government recognises the importance of safeguarding our economy from the proceeds of the most egregious human rights violations and abuses and corruption.”

But while the US Treasury has certainly not questioned the aim of economic sanctions, it has raised some important questions about their effectiveness. It says the US now faces emerging challenges to its use of these measures as a national security tool, including cybercriminals, strategic economic competitors, and a workforce and technical infrastructure under pressure from growing financial complexity, as well as competing demands from policymakers and market participants.

But perhaps the most striking thing in the report is the opening graph which shows that the use of economic sanctions by the United States has risen by 933 per cent since 2000. That must rank as one of the biggest areas of growth in international relations when, for example, by contrast Australian defence spending is up about 300 per cent in that time.

The bottom line in the analysis is that the resort to sanctions as a practical half-way house between diplomatic tut-tutting and more muscular military style interventions against nasty regimes, runs the risk of laying the groundwork for sanctions evasion strategies by the same regimes.

It’s worth repeating that the almost $1.8 billion in government money backing Telstra is more than Australia’s official annual development aid to the Pacific.

And the big sleeper here appears to be a fear that the rise of disaggregated digital or crypto currencies will undermine sanctions and even the US dollar, which is arguably the country’s biggest soft power and possibly even hard power asset.

With these deeper concerns about US economic power in mind the Treasury’s review calls for a more careful process where unintended consequences of sanctions are considered; other international policy tools to be used as well; and for sanctions to be clearly explained with both escalation and exit strategies.

But the most important finding for an ally such as Australia is that sanctions are more coordinated with international partners and implemented with better engagement with other stakeholders from the media to banks.

Law firm Akin Gump says the Treasury has long argued these positions behind the scenes but may be trying to increase pressure on other arms of the government by going public.

Phoning home

There are many ways of understanding the Morrison government’s decision to run a shadow state-owned enterprise mobile phone business in the Pacific. For example, is it Australia’s biggest single aid project or is it taking a leaf out of the Chinese playbook for soft funding of favoured businesses?

It’s worth repeating that the almost $1.8 billion in government money backing Telstra is more than Australia’s official annual development aid to the Pacific. It is also more than two times the headline total aid to the Pacific for climate change over five years, which was increased by $200 million this week. And it is the equivalent to more than half the $3 billion provided to Export Finance Australia (EFA) and the Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility as part of the 2018 Pacific Step-up.

In a situation where it is not clear if there was a potential Chinese buyer for Digicel Pacific or what happens if Telstra wants out after it gets its own money back in six years, there is one remarkably honest comment. That was Telstra chief executive Andy Penn’s acknowledgement in the announcement that the deal “represented an important milestone in the company’s relationship with the Australian government”.

Stock market investors have clearly bought the idea that Telstra has done some well protected national service in the Pacific in order to win other benefits in future on the National Broadband Network or elsewhere. Only this week Telstra signed a $1 billion five-year contract renewal with the Department of Defence.

This probably doesn’t have much impact on foreign policy. Unless, of course, another company such as a bank thought it might keep operations going in the Pacific in line with the growing government exhortations to business to remain in the region, in return for some favourable treatment at home. Westpac, for example, is trying to exit its retail banking assets in Papua New Guinea and Fiji.

The government is right to be trying to foster a business stream to the Pacific Step-up which is otherwise built on conventional aid and new forms of non-cash aid such as the Pacific labour schemes. But doing sweetheart deals with big companies such as Telstra to achieve this does have implications for, in this case, the cost of telecommunications services, which in are important to Pacific industries such as tourism and modern agriculture.

Regulators in the small Pacific countries will likely find it difficult to make the case that a government-backed Australian multinational is engaging in predatory pricing. Although it seems that PNG’s competition regulator has been able to stand up to Australian banks and Telstra could provide valuable competition for PNG’s state-owned telecommunications companies.

But with independent evaluation of aid being wound back, stock market analysts focused on Telstra getting a good deal at home, EFA worried about running a commercial insurance book and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade wanting to lure business into the Pacific, it is hard to see who is going to judge the real winner from this large investment of aid funds.