On Thursday afternoon in Boston this week, Senator Elizabeth Warren stood in front of her home with her husband Bruce Mann and dog Bailey to announce that she would be dropping out of the 2020 US presidential race.

This outcome hardly seemed likely just five months ago, when Warren was leading the crowded race for the Democratic nomination. In the weeks and months ahead of the first primaries, however, her support had slowly but steadily declined. Polls showed that while Warren excited college-educated progressives, she struggled with key constituencies within the Democratic Party: working-class voters, African-American voters, and Latino voters.

The story of the rise and fall of Elizabeth Warren’s 2020 presidential campaign will be a great case study for future political scientists seeking to understand the current political moment, even if her departure from this race is – as seems likely – only a midpoint in her political biography.

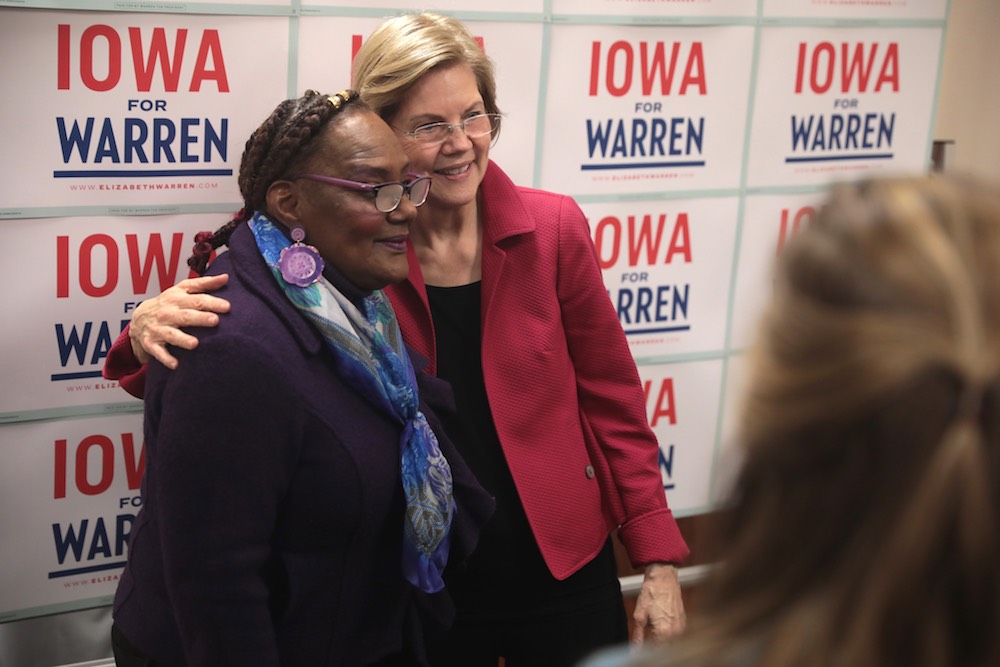

Warren was the most consistent performer throughout the Democratic debates. She raised a lot of money from small donors, and she maintained a ground operation that extended across the country. She exuded intensity and intellect on the campaign trail and reliably posed for photos with supporters for hours after her campaign events, paying special attention to little girls whom she asked to “pinkie swear” that they would consider running for office.

In her announcement, Warren expressed regret that women and girls were going to have to wait four more years for a female president. When asked about the role of gender in the race, she offered some reassurance to her supporters: “If you say, yeah, there was sexism in this race, everyone says –whiner! And if you say there was no sexism, about a bazillion women think, what planet do you live on? I promise you this—I will have a lot more to say on that subject later on.”

She exuded intensity and intellect on the campaign trail and reliably posed for photos with supporters for hours after her campaign events, paying special attention to little girls whom she asked to “pinkie swear” that they would consider running for office.

Warren was known as the candidate who had a plan for everything. Although she stumbled with her healthcare proposal, her ability to diagnose why the American economy was not working for so many people and what would be required to level the playing field was unparalleled.

Presidential campaigns often end with politicians saying that they were grateful for the opportunity to meet so many hard-working people across the country and share their ideas. Warren followed this script in her announcement, but it carried a different weight.

She reminded people how far she had come in such a short time: “Ten years ago, I was teaching a few blocks from here about what is broken in America, and pretty much nobody wanted to hear it. I’ve now had a chance to talk to millions of people. We have ideas out there that we just weren’t talking about ten years ago.”

Warren is a relative newcomer to the political scene. She grew up in Oklahoma in a family that she describes as “hanging on to its place in the middle class by its fingernails”. After time as a special-education teacher, she went to law school and then became an academic.

During the 1980s, when bankruptcy rates were skyrocketing, Professor Warren sought to understand why so many people were going bankrupt and expected to find that the people declaring bankruptcy were profligate – buying house they couldn’t afford, taking too many trips to the mall, keeping two cars in the garage.

She found that her assumptions about how people got into financial trouble were wrong: “Many of them are solidly middle-class people who got good educations, bought homes, have families. And then a serious medical problem, a job loss, a divorce or death in the family, and they were over a financial cliff.” She saw predatory credit-card companies and complicit politicians, and focused her work on calling attention to the inequities built into the American financial system.

But Warren didn’t emerge as a public figure until April 2009, when she went on The Daily Show (a late-night comedy program fluent in political commentary) in her capacity as the head of a congressional oversight panel tasked with guiding the Obama Administration’s response to the 2008 global financial crisis. Her clear-headed explanation of how stability and prosperity for middle-class Americans was undermined by decades of “pulling the threads out of the regulatory fabric” led Daily Show host Jon Stewart to comment, “That is the first time six months to a year that I felt better … That was like financial chicken soup for me.”

Warren viewed the 2008 financial crisis as an opportunity to advance significant regulatory reforms in the banking industry. She was tireless in her efforts to bring accountability to the banks and unflinching in her critique of the Obama Administration’s approach, which prioritised stabilising the banks and ensuring people got back to work over reforming the system.

Wall Street and the Republicans in Congress lined up against her. President Obama’s economic team dismissed her as an academic who lacked a grounded, realistic view of the financial industry. As a consequence, she was able to create the Consumer Protection Bureau but was not nominated to lead it. When asked about those who opposed her, Warren responded: “How much are you going to yield to corruption in the system … The system has been broken for decades. The door for real change opened a crack, and I went for it.”

In the election of Donald Trump and the soul searching that followed within the Democratic Party, Warren saw another door open for real change, and she went for it. Warren didn’t win over the Democratic electorate, but her campaign dramatically enhanced the power of her ideas.

Her campaign acknowledged recent discussions with both the Sanders and Biden campaigns about an endorsement, but her message on Thursday was, “Let’s just take a deep breath. We don’t have to decide right now … I need some space around this.”

In that space, she will likely see the next door for real change open.