The India-China border clash on the night of 15 June, the worst in over half a century, is nothing less than a chapter break in the relationship between the two countries. A dynamic that was, at the best of times, fraught with mutual suspicion is now on the cusp of becoming downright adversarial. While it would be alarmist to predict imminent war between them, it would also be myopic to rule out the possibility of limited armed conflict on the disputed India-China border in the future.

The clashes will also have a deep bearing on India’s Indo-Pacific approach and its relations with the US and its allies in the months and years ahead. It is, therefore, useful to contemplate conceptually the three lessons of the ongoing crisis for others in the region.

As analysts try to piece together the precise circumstances that led to the deaths of at least 20 Indian soldiers, it is easy to lose sight of the fact that this has been an extraordinary development, marking only the third time soldiers of two nuclear-armed neighbours have died in combat in disputed territory, along with the 1969 Sino-Soviet border clashes and the 1999 Kargil conflict between India and Pakistan.

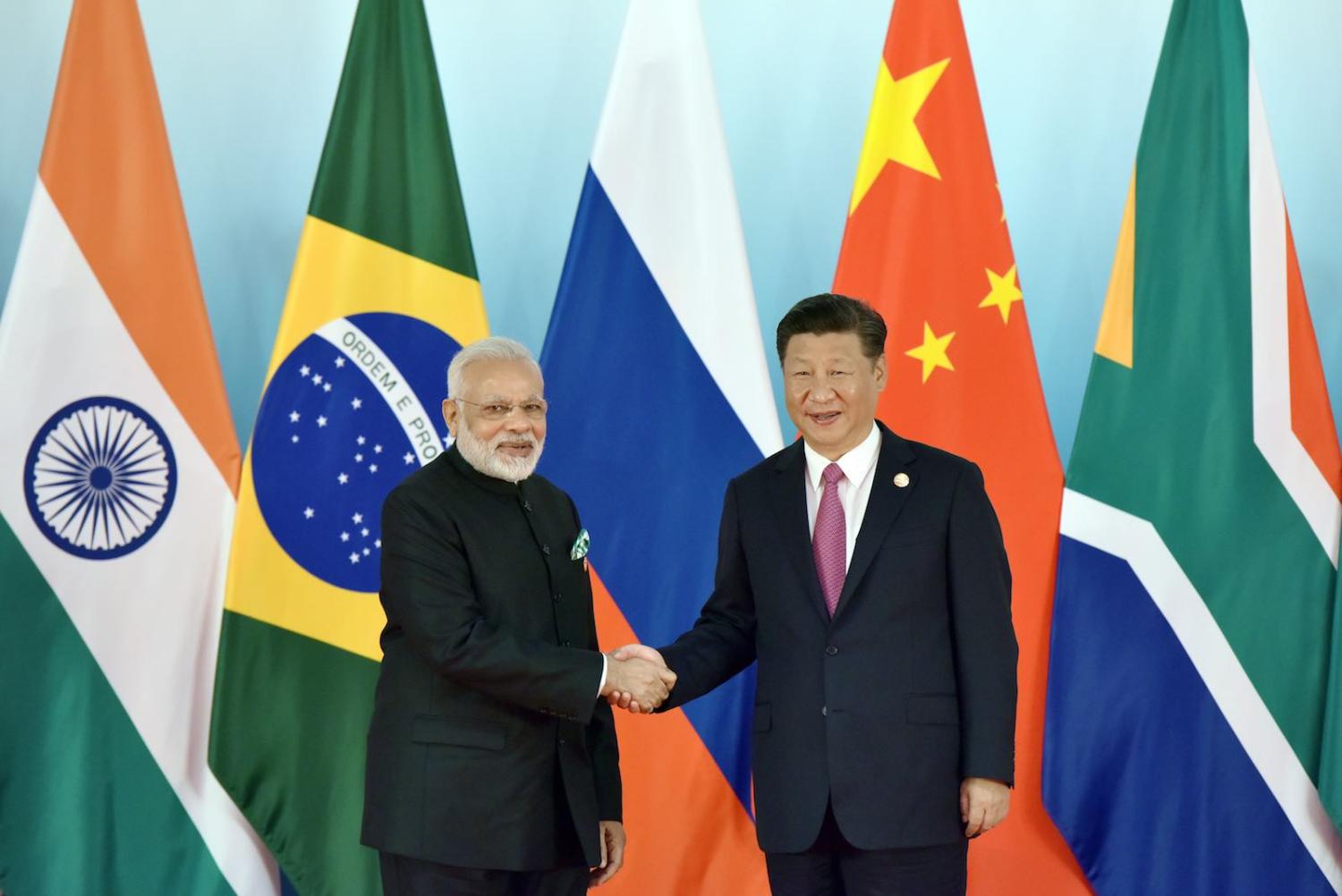

Either through accident or design, by taking on a major military power head-on, China has effectively signalled a new phase in its territorial-revisionist project. That it has sought to do so with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the mercurial risk taker and self-projected national-security hardliner, at the helm says much about the risks China’s President Xi Jinping is willing to run. That alone should give Indo-Pacific watchers everywhere pause.

Regional stakeholders now need to effectively factor in the continental dimension of the India-China rivalry as they seek to draw New Delhi closer in any China-balancing or even containment effort.

As far as New Delhi is concerned, Chinese bad behaviour has been a permanent part of its strategic calculus, even when India has downplayed it. A large part of the non-territorial strategic calculus between the two countries revolves around Pakistan, whether related to Chinese infrastructure projects passing through territory India claims or Beijing’s prolonged military support for Islamabad.

Analysts on both sides (including one affiliated with a Beijing-based think tank) have suggested that India’s decision last August to revoke Kashmir’s autonomous status within its constitution, as well as to carve out a new centrally controlled territory that includes Chinese territorial claims, may have provided the opening Beijing needed to initiate the current standoffs in eastern Ladakh.

Without litigating the merits of this claim, one thing is clear. For India, its Pakistan travails, as well as its increasingly contentious relationship with smaller neighbours such as Nepal, are “part of China’s growing geopolitical impact all across the Great Himalayas,” as C Raja Mohan put it in a recent article on the crisis. Consequently, India’s China pushback, beyond the exigencies of the current crisis, will be framed by an incipient anti-India strategic chain that pivots around China.

Therefore, regional stakeholders now need to effectively factor in the continental dimension of the India-China rivalry as they seek to draw New Delhi closer in any China-balancing or even containment effort. Despite the comments of US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo that hinted at a parity between Chinese intransigence elsewhere and its ongoing actions on the India-China boundary, it is unclear to what extent the American Indo-Pacific strategy has considered the boundary dispute between India and China as a core geostrategic challenge in the region.

The US Defense Department’s 2019 Indo-Pacific Strategy Report did suggest that the US considers the Indo-Pacific both a maritime and a continental theatre: witness, for example, the prominent place accorded to landlocked Mongolia. Indian military assets procured from the US such as the P-8I maritime patrol aircrafts have been repurposed by India to monitor developments on land, most notably during the 2017 India-China Doklam crisis during which the US also provided crucial intelligence, surveillance and reconaissance support to India.

That said, US diplomats have alluded off the record to a hard ceiling to the kind of support India can expect during a China crisis. Absent a formal treaty relationship from which the US can’t back down, it must privately discuss the support it would be willing to extend to India in a land conflict with China.

The same applies to Australia. The statement by Foreign Minister Marise Payne was measured and cautious. But Canberra – as it continues its bullish streak when it comes to New Delhi – must ask itself what (if anything) it can do should an India-China crisis spill into a shooting war. Hugh White’s optimism that the Himalayan terrain would serve as a natural damper to further escalation may turn out to be misplaced, especially given that 21 years ago, India and Pakistan fought an intense war in Kargil – in what now constitutes western Ladakh.

Beyond how the 3488-kilometre disputed border between the two countries fits into regional Indo-Pacific strategies, there is a larger point that often gets missed: it is as much a forefront of tussle around Chinese revisionism as is the western Pacific. As Alyssa Ayres writes, the India-China border “needs to be on the US foreign-policy radar screen as a frontline for Chinese assertiveness”. Compared to the jostling in the South China Sea, it has simply not figured as an Indo-Pacific priority for the US, Australia or Japan.

The reasons behind this are historic. A 2005 study of the US-India defence relationship noted that India fell into “strategic ether between the two powerful unified commands [the erstwhile PACCOM and CENTCOM]”. While over the past 15 years this situation has been remedied to a considerable extent, US interest in seeing India share its burden in the region has been predominantly in the maritime space, as a “net security provider” in the Indian Ocean region. But India’s geography dictates that it keeps its eye on the ball when it comes to China, both on land and on the high seas. India’s partners must appreciate this unique strategic circumstance the country finds itself in.