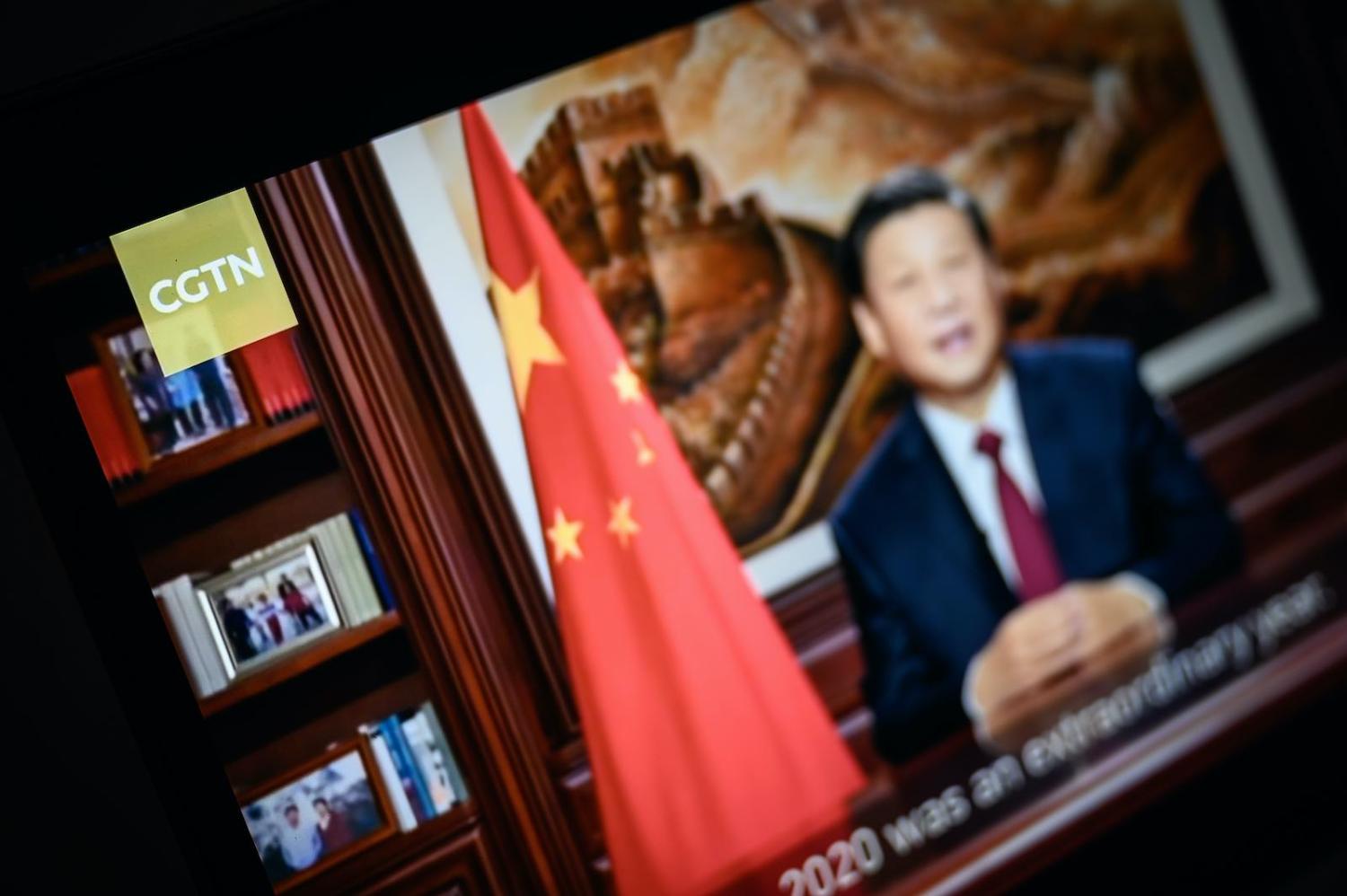

When China began three days of military exercises in the South China Sea’s Gulf of Tonkin back in January, some observers speculated that Beijing was testing the new Biden administration. Harsh words from Beijing accompanied the exercises, with China’s foreign ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin declaring the drills were “necessary measures to resolutely safeguard national sovereignty and security”.

Even against this backdrop, China’s official position is that it remains committed to a peaceful resolution of the South China Sea issue. And the rhetoric China employs at different times does make for a fascinating contrast. For example, China’s Foreign Ministry asserted in July 2020 that “China is not seeking to become a maritime empire” and that it “treats its neighbouring nations on an equal basis and exercises the greatest restraint.”

How then should we make sense of the mixed messages coming from Beijing? Most China experts find discourse to be informative – if not about China’s intentions, then at least about its aspirations. But which statements are indicative of China’s true position?

I argued recently in research for the Wilson Center that scholars need to evaluate the content and specificity of Chinese national discourse in addition to the position of the author or speaker involved. To that end, I analysed all public speeches made by members of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party from 2013 to 2018. Xi Jinping led both of the Politburos I studied, and each had 25 members. Since some members served in both, this yields speeches by 39 unique individuals.

Ambiguity suggests the leadership wants to have maximum flexibility and avoid being boxed in by its aggressive rhetoric.

The speeches related to the South China Sea could be separated into those that mentioned cooperative themes and those with competitive themes. Cooperative themes have two subcategories, cooperation and political solutions. Competitive themes have five subcategories: sovereignty, military, freedom, tension and non-regional countries/the United States.

In what might appear good news for regional stability, China’s leaders used more cooperative discourse in public statements about the South China Sea than competitive themes. This might be taken to indicate a willingness to compromise with other claimants – a feature that is especially evident during the first year of each new Party Congress, namely 2013 and 2018.

However, one of the tenets of deriving intentions from discourse is that not all leadership statements are created equal. We need to consider personal power, accountability and reputation for honesty. This means that statements by Xi, who is described as having “more power and more personal authority than any post-Mao leader”, take precedent.

So here is the bad news. My analysis showed that Xi’s statements accounted for 42.7% of the competitive themes mentioned, even though he is only one of 39 leaders during this period.

There are additional reasons to discount Xi’s cooperative statements: his reputation for dishonesty.

In September 2015, Xi made a public statement at the White House promising not to “militarise” the artificial islands China had been building in the South China Sea. Xi stated that “relevant construction activities that China is undertaking … do not target or impact any country, and China does not intend to pursue militarisation”. While the language at the time was deemed “new”, the pledge remained unclear. Then and subsequently, Xi did not promise to freeze dredging, island-building or activities in the region, nor did he offer any clarity about what “militarisation” meant. In May 2019, then–Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford said that China had “clearly … walked away from that commitment” given the “10,000-foot runways, ammunition storage facilities, routine deployment of missile defence capabilities, aviation capabilities and so forth” on the islands. My analysis in a previous Interpreter article shows that China has indeed militarised these islands to establish control over the islands and the surrounding waters.

Interestingly, China’s foreign ministry also makes more competitive statements than cooperative statements, contrary to what might be the expectation that professional diplomats would lean towards negotiations and reassurance. If soothing language was supposed to mask China’s intentions, ministry statements would be the most likely source. But instead, China seems to prioritise articulating its position on sovereignty and issuing threats to those who violate it over reassurance.

None of this means China will use force in the South China Sea. Xi’s statements calling for a tough stance to protect China’s perceived sovereignty in the South China sea lack specificity – there are no allusions to a timeline or preferred methods. Such ambiguity suggests the leadership wants to have maximum flexibility and avoid being boxed in by its aggressive rhetoric, even if it is popular with the Chinese public. And the Chinese leadership undoubtedly prefers to use diplomatic, legal and economic tools to establish sovereignty over these waters.

But my analysis suggests that China will be unlikely to make the compromises necessary on its expansive territorial claims in these waters to facilitate a viable diplomatic resolution. Instead, China’s leaders hope that political, economic and military power will convince other countries to accommodate China’s position without a fight. And if the other claimants concede to Beijing, it will be harder for the United States or Australia to push back on China’s position.