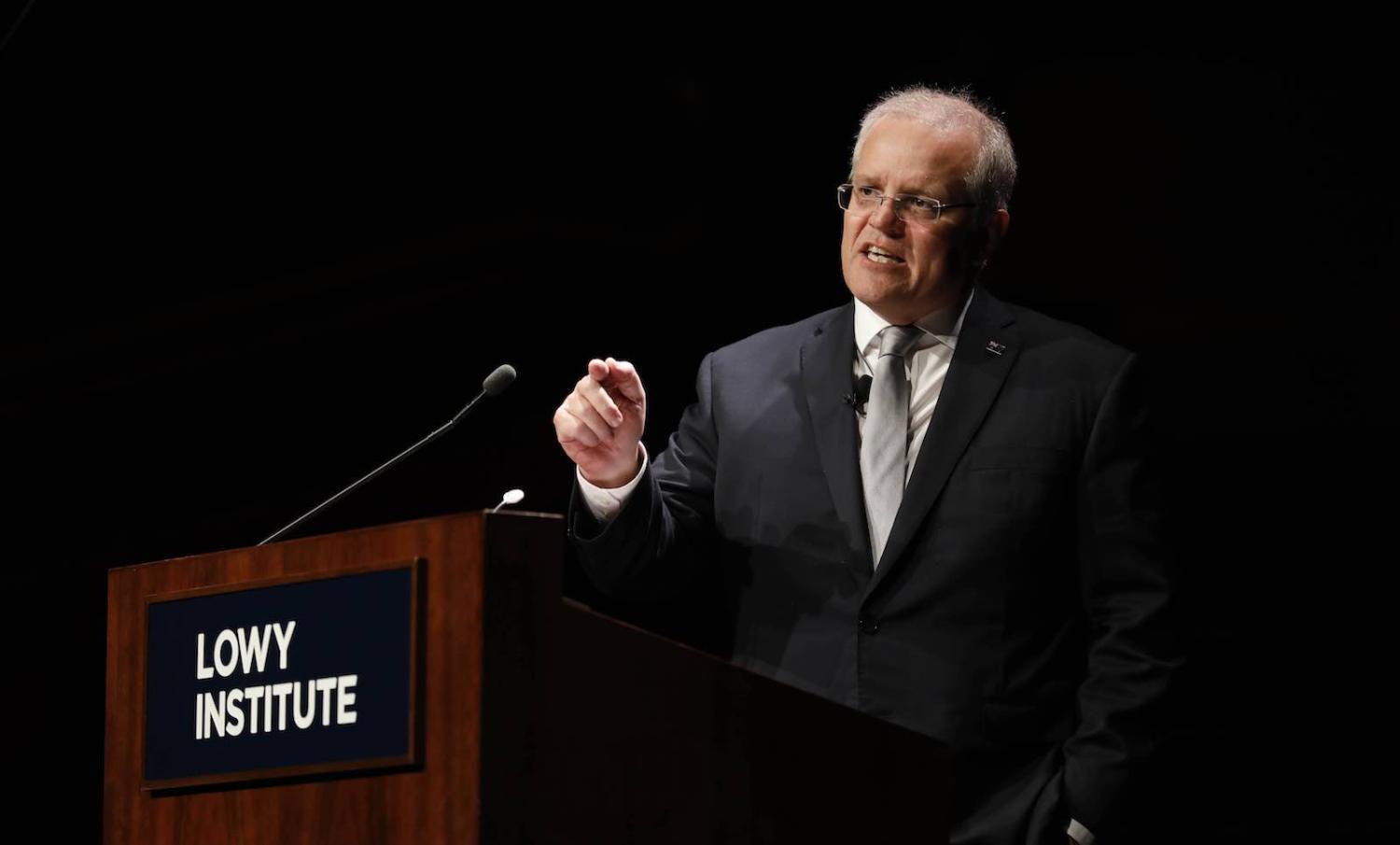

Paul Kelly’s recently published book, Morrison’s Mission: How a Beginner Reshaped Australian Foreign Policy, provides the most detailed account yet of the formation of the country’s foreign policy since Scott Morrison became prime minister in 2018 and is full of useful insights.

The Forever Partnership

A central feature of what Kelly calls the Morrison Doctrine is the Prime Minister’s confidence in America, and in Australia’s “forever partnership” with the United States. Kelly portrays this commitment as more than rhetorical. He argues that Morrison understands “the risk that America might be a less reliable senior partner because of its domestic fractures, but it is a risk he is prepared to take … Morrison believes the bigger gamble for Australia lies in hedging its bets – deciding on more accommodation of China.”

Kelly endorses this approach. He acknowledges “powerful critiques” from analysts and former officials Hugh White, James Curran, Geoff Raby and Allan Gyngell, but concludes that:

“they neither sketch out a viable alternative policy nor confront the real choices an Australian prime minister such as Morrison faces in office. No prime minister would lightly downgrade or hedge on the US alliance at the precise time China is flexing its muscles. The idea that China would offer Australia anything for distancing itself from the United States is fanciful.”

This is because, according to Kelly, whatever “internal traumas” the United States might face, it will “remain the leading military power for some years yet”. As for the alliance, it has “become a bureaucratic institution in its own right”. The storied Dennis Richardson, who probably knows the alliance better than anyone else, underlines that it “has never been held hostage to one personality … that was the case during the Trump presidency and would be the case in the future”.

She won’t be right

This assessment of the range of possible US futures and the consequent choices for Canberra is too narrow.

Kelly is correct that Australia fared better than perhaps any other US partner under former US President Donald Trump. After a rocky start, Trump warmed to Australia. The relationship’s depth and breadth – built up through years of determined diplomacy – gave it ballast and enabled some progress on the common goal of constraining Chinese power.

But there is no reason to assume that should Trump win a second term it would be a re-run of his first. Canberra cannot even assume that he would be a dependable ally against China. Although Trump ended his term in an anti-China stance, his approach to Beijing was all over the place. His admiration of strongmen extended, episodically, to China’s President Xi Jinping.

The damage inflicted by Trump on US standing and the international order was limited by his inexperience, incompetence and an entrenched bureaucracy.

Trump was, however, consistent in his hostility to the international system that Washington established after the Second World War and, more specifically, to America’s alliances with Japan and South Korea. It’s not hard to imagine him trying to strike a “great deal” with Xi that would see America cutting back its expensive security commitments in the Indo-Pacific.

The damage inflicted by Trump on US standing and the international order was limited by his inexperience, incompetence and an entrenched bureaucracy. But those are short-term obstacles. Trump became progressively more hostile to the so-called “deep state” throughout his term. Fuelled by QAnon conspiracists, he would almost certainly assault national security bureaucracy more directly if given another chance. The institutional power of the ANZUS alliance – highlighted by Kelly – rests on the integrity of that bureaucracy.

A second Trump term could also see America’s soft power replaced with sharp power – more meddling in democracies such as Australia. Australia’s “tyrannical” approach to Covid-19 has assumed a central position in the Trumpist imagination. Trump’s ambassador to Germany openly declared his intention to “empower other conservatives throughout Europe”. And there are clear links between far-right extremism in both countries.

Don’t predict, prepare

Of course, none of this may come to pass. The point is not to predict America’s future but to recognise that the United States – long a key constant in Australia’s international environment – is now the main variable. And the range of plausible scenarios is wide. It includes contested election results and ongoing instability. The path back to normalcy, by contrast, looks increasingly narrow. It would require not just Trump’s electoral failure but – at minimum – the widely accepted win of a mainstream Democrat or (less likely) Republican presidential candidate in 2024.

Kelly narrows Canberra’s options to one: where to position itself on a line between Washington and Beijing. He is correct that Australia should not appease China and could not simply cut and run from an unstable, and perhaps even illiberal, America. But the choices presented by both China and the United States will be more numerous and complex than that.

If anti-democratic forces within the United States threatened Australian democracy, Canberra might have to push back publicly.

To maintain a useful relationship with the United States that is domestically supported, Australia may need to make some calibrated changes. If Trump returned, it might, for example, need to quietly adjust security and intelligence cooperation, especially if Trump once again shared secrets with adversaries. At the other end of the spectrum, if anti-democratic forces within the United States threatened Australian democracy, Canberra might have to push back publicly (in a way that Morrison didn’t need to after the 6 January attack on the Capitol).

All alliances are breakable

Australia’s preparation for an unpredictable America faces structural impediments. The national security bureaucracy is not geared towards assessing the United States with the same objective distance with which it views countries such as China. Canberra’s understanding of the United States is, however, strongly shaped by the personal connections that have deepened under the alliance’s umbrella. And wishful thinking is human nature.

Mateship is a double-edged sword. The steady growth in mutual trust has been a major achievement of persistent diplomacy on both sides and has laid the ground work for ever closer cooperation, as embodied in the AUKUS security pact. These relationships give Canberra good insights inside the beltway. But they can also encourage Australian decision-makers to miss or rationalise warning signs of fundamental change.

That tendency is sometimes described as a “boiling frog” problem (based on the apocryphal story that frogs cook to death rather than jumping out of slowly heated water because they don’t notice incremental change). A “boiling frog” is best avoided by articulating a falsifiable theory and describing the evidence that would cause a reassessment.

Publicly trumpeting the #UnbreakableAlliance makes good diplomatic sense, but behind closed doors Canberra needs to develop an understanding of what would break it and how.