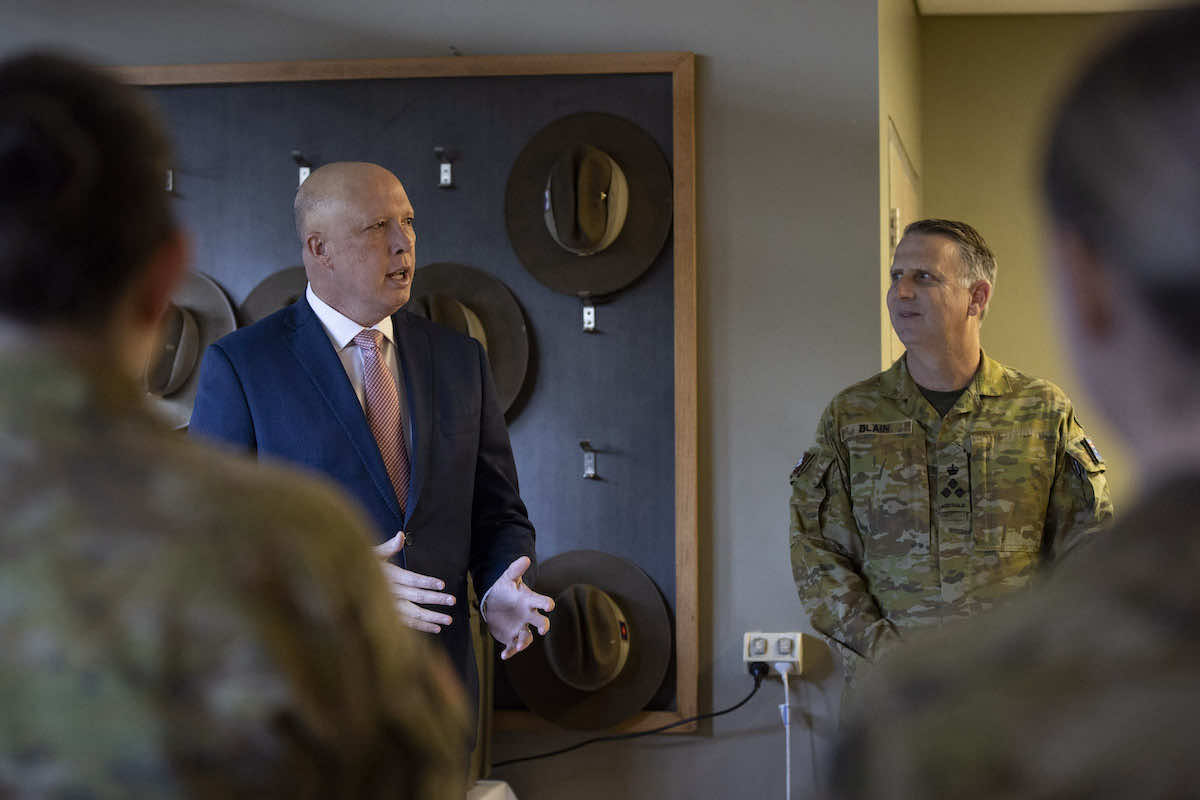

Last week, Peter Dutton gave his first speech as Minister for Defence.

In his remarks and follow up Q&A, Dutton touched on the increasing risk of war “especially through miscalculation or misunderstanding”, the challenge of China, and the relationship with the United States as being “core” to deterring threats to Australia. In this more troubled world, Dutton further noted, Australia would seek to improve its security by strengthening US engagement, including by potentially hosting more American forces in Darwin and Perth.

On the face of it, these points are sensible enough. An increased US presence would practically improve Australia’s defence potential by enhancing training with the world’s preeminent military power as well as swelling the quantity of armed forces that any adversary would face if directly attacking the continent.

Despite this, Dutton’s proposals should be matched with more cautious language to signal that where the US goes, Australia does not necessarily follow. Otherwise, the government’s American remedy risks exacerbating Australia’s security malady.

This is because the most grievous defence risk facing Australia, involvement in a shooting war with China, is most likely to occur as a consequence of US engagement rather than any separate issue between Canberra and Beijing. This reflects a lack of issues between Australia and China that might cause a “miscalculation or misunderstanding” leading to war: there is neither an over-arching militarised competition, or any specific hot-button matters that may serve as immediate and direct tripwires.

In contrast, US great power competition with China will likely span decades. There are also numerous tripwires ranging from ongoing Freedom of Navigation Operations in the South China Sea, through to Washington’s defence commitments to the Philippines, Taiwan and Japan – all nations facing security disputes with Beijing. Should any of these flashpoints (as opposed to a direct attack on Australia or its forces) lead to conflict, Australian involvement should be an open question.

Do Australians really want to send warships to fight over contested atolls in the South China Sea? Or troops to fend off an attack on Taiwan? Would Australia make much difference if it did?

As I’ve written before, in these scenarios Canberra might want to take the sensible approach Washington did with London before Pearl Harbour: provide diplomatic, logistic and intelligence support, but keep away from the shooting until shot-at first.

But this will be much harder to achieve if the strategic mindset in Australia and America is “one-in, all-in”. And Beijing will have more incentive to attack if it believes Australia’s front-line involvement is inevitable. Better to send submarines and sink ships at dock, for instance, rather than waiting for them turning up in battle supporting the US.

So, how can Australia have its cake (the practical security benefits of more US engagement) and eat it too (not being dragged into a war it is trying to avoid)?

More is needed to elevate, in parallel to expanded engagement, a message that Australia is a peaceful nation that will only engage in military actions as and where it sees fit.

A key answer is keeping the defence cooperation but with better signalling – to both Washington and Beijing. Neither China nor the US should assume Australia will be in the thick of any fighting just because of its American relationship (noting in any case that the ANZUS Treaty only requires the parties to “consult” in the event of a conflict).

As part of this, Dutton’s future speeches might better note that the only thing “core” to deterring attacks on Australia is the Australian Defence Force, not the US alliance.

And more is needed to elevate, in parallel to expanded engagement, a message that Australia is a peaceful nation that will only engage in military actions as and where it sees fit, unless its hand is forced by an attack. A conscious policy of strategic ambiguity might serve this role well – and also cool tempers in both Beijing and Washington.

Such a balanced approach provides a good option to pursue what should be the objective of any government policy (security or otherwise): maximising the benefits for Australia (and Australians) while minimising costs.

On this note, Dutton also remarked that “we cannot simply seek to ring-fence Australians from complex and difficult issues.” Yet this is precisely what Canberra (or any other capital) should be aiming to achieve for its polity. In his upcoming speeches (and policies) this objective should be better recognised and pursued.