One might wonder how something as small as five nanometres – about the width of two strands of DNA – could be of consequence to the complex political relationships between the US, China and Taiwan.

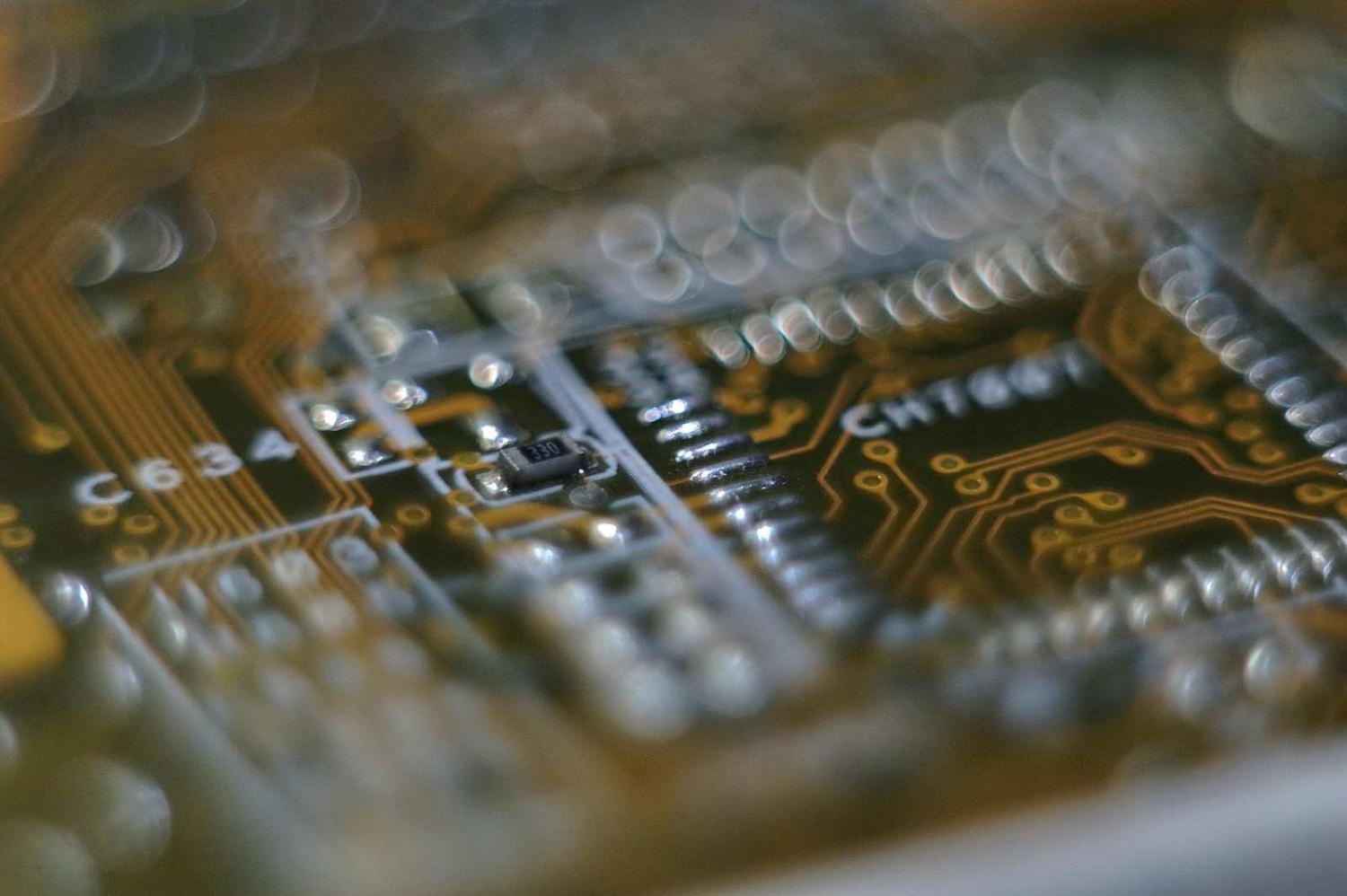

Semiconductor chips are the brains of all our electronics, from mobile phones to cars to fighter jets. And the most advanced chips on the market today have billions of five nanometre switches on them.

Taiwan has a dominant role in the international supply chain for these tiny but strategically vital products. Together with South Korea’s Samsung and Intel from the US, Taiwan is at the cutting edge of semiconductor technology. It is also a major presence in their manufacturing: one Taiwanese company, TSMC, produces about half the world’s annual supply of chips.

The industry has been a diplomatic asset for Taiwan, entrenching US and Chinese interests in Taiwan’s stability and autonomy.

Taiwan’s semiconductor industry has deep links to the US. This is not surprising when you know the history. Taiwan’s sector took off in the 1970s and 1980s when Taipei was looking for a way out of an economic slump caused by the 1973 oil shock. A combination of industry policy and unlikely personal connections with leaders in the Radio Corporation of America saw a generation of Taiwanese engineers trained in the US. Today, almost all major US technology firms have some presence in Taiwan. The US sources its most advanced chips for military hardware from TSMC – chips it is unable to make at home. Taiwan is also the second-largest market for US semiconductor equipment.

But China’s emergence as the world’s largest consumer of semiconductor chips has led Taiwan to develop links there, too. Since the early 2000s Taiwanese semiconductor firms have radically increased sales into the Chinese market. And the benefits of this relationship run both ways. China’s domestic manufacturing meets less than a fifth of domestic demand for chips and is about five years behind the technology frontier. China leans heavily on Taiwan’s manufacturing capacity for the chips vital to its electronics industry, including some of its most profitable export lines.

The Taiwanese semiconductor industry’s vested interests in both the US and Chinese markets have seen it quietly lobby for Taipei to maintain friendly ties with both sides. But Taiwan’s status as a neutral player is becoming harder to maintain. With US-China tensions rising, both fear the influence of the other over their supply of chips.

The US technology war with China, by a combination of both default and design, is pulling Taiwan closer into the orbit of the United States.

Under the Trump administration, the US has become more pro-Taiwan than at any time since it switched diplomatic recognition to Beijing in 1979. This policy is more a confluence of many interests than clear strategic vision. With the White House largely looking the other way and anti-China sentiment running high, pro-Taiwan elements in the US concerned with historical or geopolitical reasons for Taiwan’s continued autonomy have been vocal in shaping policy. And they’ve found support from elements within the national security apparatus who want to exert influence over Taiwan’s technology sector and ringfence it from China.

The US technology war with China, by a combination of both default and design, is pulling Taiwan closer into the orbit of the United States. There have long been reports of US pressure on Taiwanese semiconductor companies to resist sales to China and do more manufacturing in the US. In May, this culminated in both an announcement from TSMC that it would spend US$12 billion on a US manufacturing plant (with an unspecified amount of US government support) and a technical change to export rules.

New export rules in the US designed to target Huawei will have big implications for Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturers such as TSMC. In the past, TSMC earned nearly a fifth of its revenue from sales to China. But much of that has ground to a halt. Because TSMC uses US semiconductor equipment to make the chips it sells, there are now limits on who it can sell to. The rules mean TSMC will be ever more reliant on the US market for sales.

For China, the new rules won’t bite for a little while. Huawei has reportedly stockpiled a year’s supply of chips. There has also been some media speculation about an exemption – will TSMC’s US$12 billion investment in the US buy it some leeway? And a year is a long time in both politics and technology; whether China can negotiate, or innovate, its way out of this dilemma is anyone’s guess.

The ability of Taiwanese semiconductor firms to seek out friendly ties with both the US and China is also made harder by the ideological approach of President Xi Jinping to Taiwan’s status. One might think that China’s dependency on Taiwan for chips might endear it to the status quo. But Xi isn’t such a realist when it comes to Taiwan. Beijing views Taiwan in largely political terms – preoccupied with “the great trend of history” towards unification, as Xi claimed in his January 2019 speech which soured cross-strait relations. This is because ideas of the Communist Party’s legitimacy are tightly bound together with control over China’s territory and historical sovereignty of Taiwan. Save for paying handsome salaries to attract Taiwanese talent, China’s increasingly hostile policy to Taiwan is remarkably at odds with its trade interests.

The technology war, increasingly nationalist trade policies in the US, and ideological hardening in China mean that Taiwan’s ability to keep calm and carry on is getting tricker. And the semiconductor industry is where politics gets real for Taiwan. The industry accounts for around 15% of Taiwan’s GDP, so there’s a lot at stake. Taiwan’s dominance in this tiny but strategically important technology is becoming another layer of complexity in the US, China, Taiwan triangle.