Donald Trump has now become the first US president in history to be impeached twice, this time for “incitement of insurrection” for his role in last week’s violence in Washington. Yet as the US reels from the storming of the US Capitol building – civil strife which some analysts had warned of weeks, months or even nearly a year beforehand, and with the potential for more trouble to follow – attention is turning to how this situation will influence US domestic and foreign policy in the Asia-Pacific region.

In the coming months, this domestic civil strife is likely to engender a “relative strategic shift” in the Asia-Pacific, where more ambitious great and middle-power actors will advance against weakened democratic partners and allies amid an accelerating “third reverse wave” in a global trend of retreat from democratic freedoms.

China’s latest effort to make support for democracy a crime in Hong Kong is merely one example.

In this new strategic environment, great and middle-power countries in the Asia-Pacific region will likely augment the total number and intensity of tit-for-tat and/or grey-zone operations to pursue political, strategic and operational ends without actually resorting to open conflict.

This may arrive in a variety of contexts or potential flashpoints, ranging from Russia’s use of its newly acquired naval ships by the Pacific Fleet, replicating China’s three-stage process in the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands dispute in the Kuril Islands dispute against Japan, to North Korea’s enhancement in the quantity and intensity of its grey-zone operations on maritime and land frontiers with South Korea, while the United States is preoccupied by cyclical North Korean nuclear testing around the presidential inauguration (the so-called “provocation window”).

The inability to project power beyond militarised means will make allies and partners far less confident in the depth and durability of the US commitment to the Asia-Pacific region.

Another possible context or flashpoint is China’s record-breaking number of naval ships around the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands and Taiwan transitioning to the Pratas Islands in response to the Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s announcement that the United States will end its decades-old restrictions on official contacts with Taiwan. The arrival in Taipei of the United States ambassador to the United Nations, Kelly Craft, is evidence of the outgoing Trump administration’s commitment to this announcement.

With a surging number and intensity of tit-for-tat and grey-zone operations, small-to-middle powers in the region – especially in Southeast Asia – will start the process of reassessing whether their overall security relationship with the United States is sufficient to maintain their own security priorities.

As a result of this reassessment, some of those small-to-middle-powers will adopt a “dual policy” of publicly showing the United States that they remain committed to standing security arrangements while the US prioritises its domestic issues, but also simultaneously aggressively hedging in private to better position themselves with other states. Similar to Australia, Southeast Asian states will be divided on the best way to approach the relative strategic shift. While some will look cautiously outside of the Asia-Pacific region (e.g., the European Union, France, the UK and India), others will be forced to look at actors closer to home inside the region (e.g., China and Japan).

Representing the latter group, Thailand, which sought to balance China through its historical friendship with the United States, will be put in a particularly difficult corner, as the multifaceted Chinese political and economic charm offensives through its “good neighbour-style foreign policy” will face no serious counterweight. Thailand's growing foreign policy imbalance between China and the United States has only accelerated further during the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, after China donated 1.3 million surgical face masks, 70,000 N95 face masks, 150,000 Covid-19 test kits and 70,000 personal protective equipment suits to support Thailand’s fight against the virus.

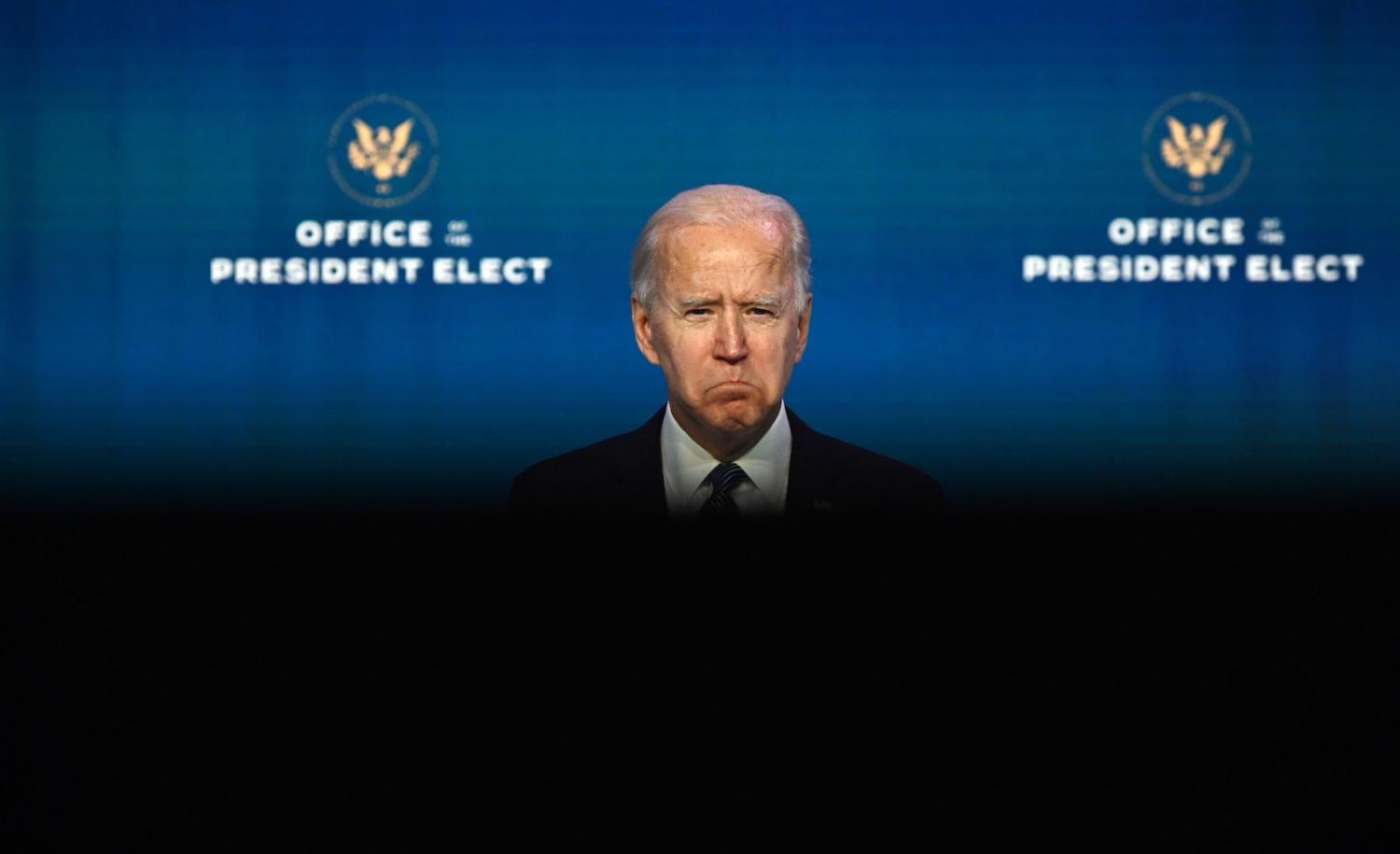

Some have forecast that Joe Biden’s multilateral approach will help rescue the Trump administration’s failed foreign policy approach across the Asia-Pacific region (notably in Southeast Asia) and could reverse such a strategic shift. One of the tenets described in this return to a multilateral approach is the US (re)joining a host of international organisations and programs, including the World Health Organisation’s Covax initiative, which aims to provide two billion Covid-19 vaccines by the end of next year to underdeveloped countries.

However, to the extent that US success within international organisations and with partners is undergirded by US soft power, Biden’s influence will be gravely weakened with each passing domestic crisis. Whereas in the past American soft power was systematically a strength towards aggrandising the United States’s authority abroad it will now mostly have the reverse effect. Therefore, the Biden administration’s projected “no-frills” or “business almost as usual” approach (echoing the Obama-Clinton foreign policy era) is likely to be incompatible with a new international environment and this strategic shift.

Consequently, in the coming years, the US government will heedlessly continue the process of militarising its foreign policy in an attempt to mitigate the diplomatic failure to reverse the slow-moving strategic shift that will occur in the Asia-Pacific region.

The inability to project power beyond militarised means, elicited by intermittent domestic crises, will make allies and partners far less confident in the depth and durability of the US commitment to the Asia-Pacific region. The likely result will be that the United States is once again be long on promises, but short on delivery.