The 2008 financial crisis accelerated China’s emergence as a global power in ways that Beijing found unsettling. The economic mess in the North Atlantic world thrust the People’s Republic of China into a global position that it had thought would take a generation to reach. Suddenly China could no longer claim, Uriah Heep style, that it was a humble emerging economy: the financial crisis had made it unambiguously one of the world’s two most important powers alongside the United States. And with that rank would come, inevitably, expectations for the PRC to bear the burdens that go with being a great power and to do so in the full glare of the world.

In the intervening years Beijing has grown somewhat more comfortable in the limelight but remains uncertain about how best to approach the expectations of global leadership.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine presents the biggest diplomatic challenge the PRC has had to face since the financial crisis. How will the world’s other genuinely global power respond to a major threat to Eurasia’s strategic balance?

Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison, for his part, has repeatedly called on China “to take as strong as a position as other countries in denouncing what Russia is doing”.

Actively cheering on Russian behaviour is impossible given that the invasion flies in the face not only of the principles at the heart of Chinese foreign policy but would earn it opprobrium in many parts of the developing world.

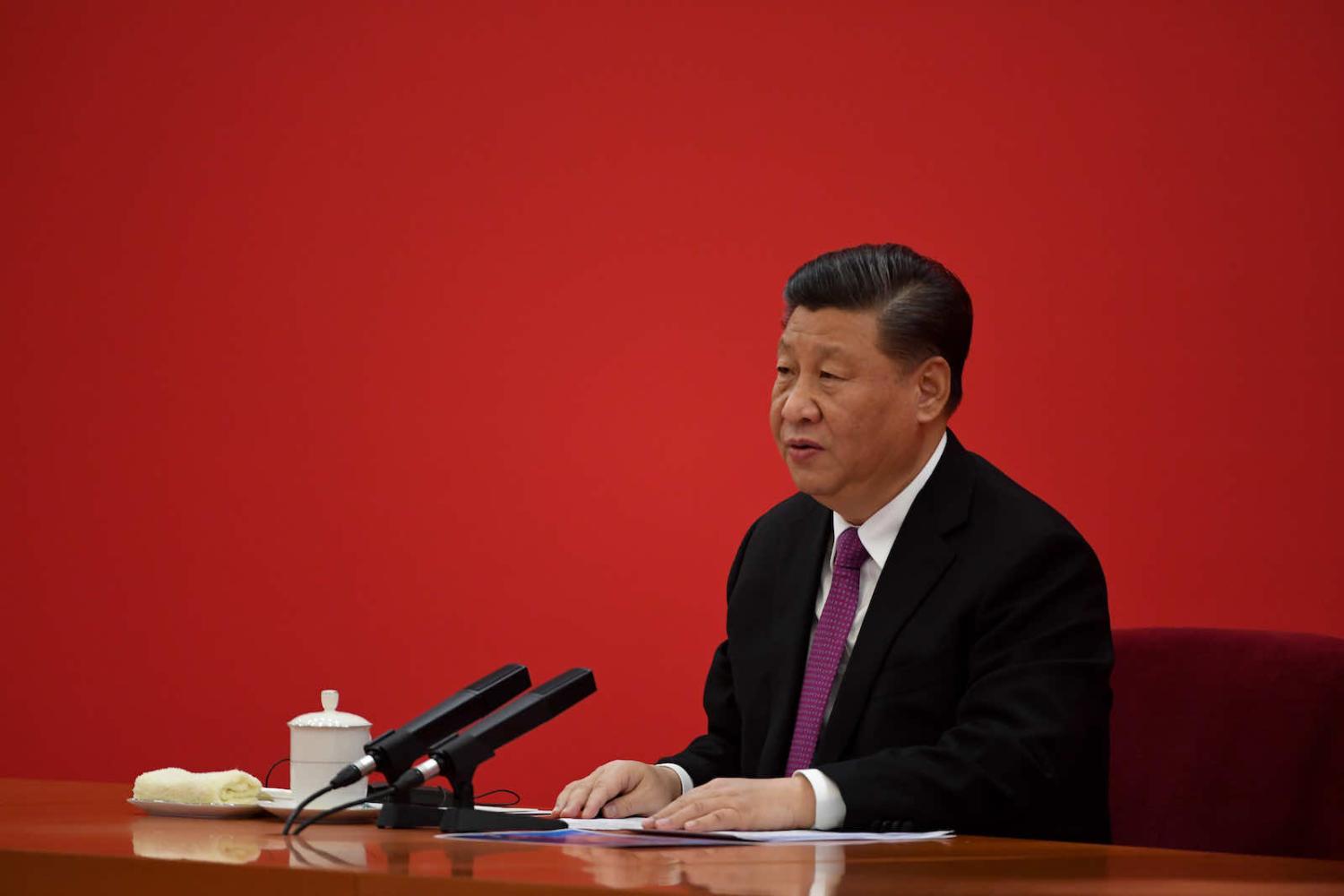

For decades, the PRC has insisted on traditional views of sovereignty and a strict adherence to principles of non-interference. These have been central to China’s President Xi Jinping’s approach to the world, defending the PRC’s behaviour in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, while pushing for these ideas of sovereignty and non-interference to play a more prominent role globally. But China has also been motivated by a desire to unsettle US foreign policy and weaken America’s global position. These goals pull Beijing in very different directions.

Above all else China wants stability in 2022. The 20th Party Congress will be held in the Northern Hemisphere autumn and the Chinese Communist Party’s utmost priority is ensuring stability at home and abroad in the run up to this five-yearly political jamboree. Xi is expected to cement his role as paramount leader entrenched in power indefinitely at the Congress.

The challenges from the pandemic remain significant within China, particularly given the party’s continued adherence to a Covid-zero policy in the face of the contagious Omicron variant. Economic threats also abound, most visibly in the property market crisis. Xi’s many enemies will be emboldened by signs of weakness that come from problems at home or missteps abroad.

So what will China do? It has very publicly agreed to a “no limits” strategic partnership with Russia, and, given the two countries’ shared interest in weakening the United States and its alliances, this means that the PRC has to support Russia. But it will only do so tacitly. Actively cheering on Russian behaviour is impossible given that the invasion flies in the face not only of the principles at the heart of Chinese foreign policy but would earn it opprobrium in many parts of the developing world, where democracies may be thin on the ground but opposition to conquest and imperialism remains strong.

In the short term the PRC is likely to revert to its practice at the UN Security Council of keeping a low profile and when it speaks to do so in diplomatic platitudes. Yet Beijing will find ways to signal ongoing indirect support for Moscow, and may well help it financially in the event sanctions begin to bite. China sees long term benefits in the partnership but recognises that the relationship with Russia rests on fragile foundations. It will also be quietly trying to ensure Vladimir Putin keeps the crisis from escalating militarily and settles down by the middle of the year.

Xi puts a great store on presenting a confident Chinese face to the world, one capable of being among the world’s pre-eminent powers. But he is discovering that that game is difficult and when partnered with Putin’s Russia it comes with a level of risk for which Xi may not have bargained.