Buyer beware

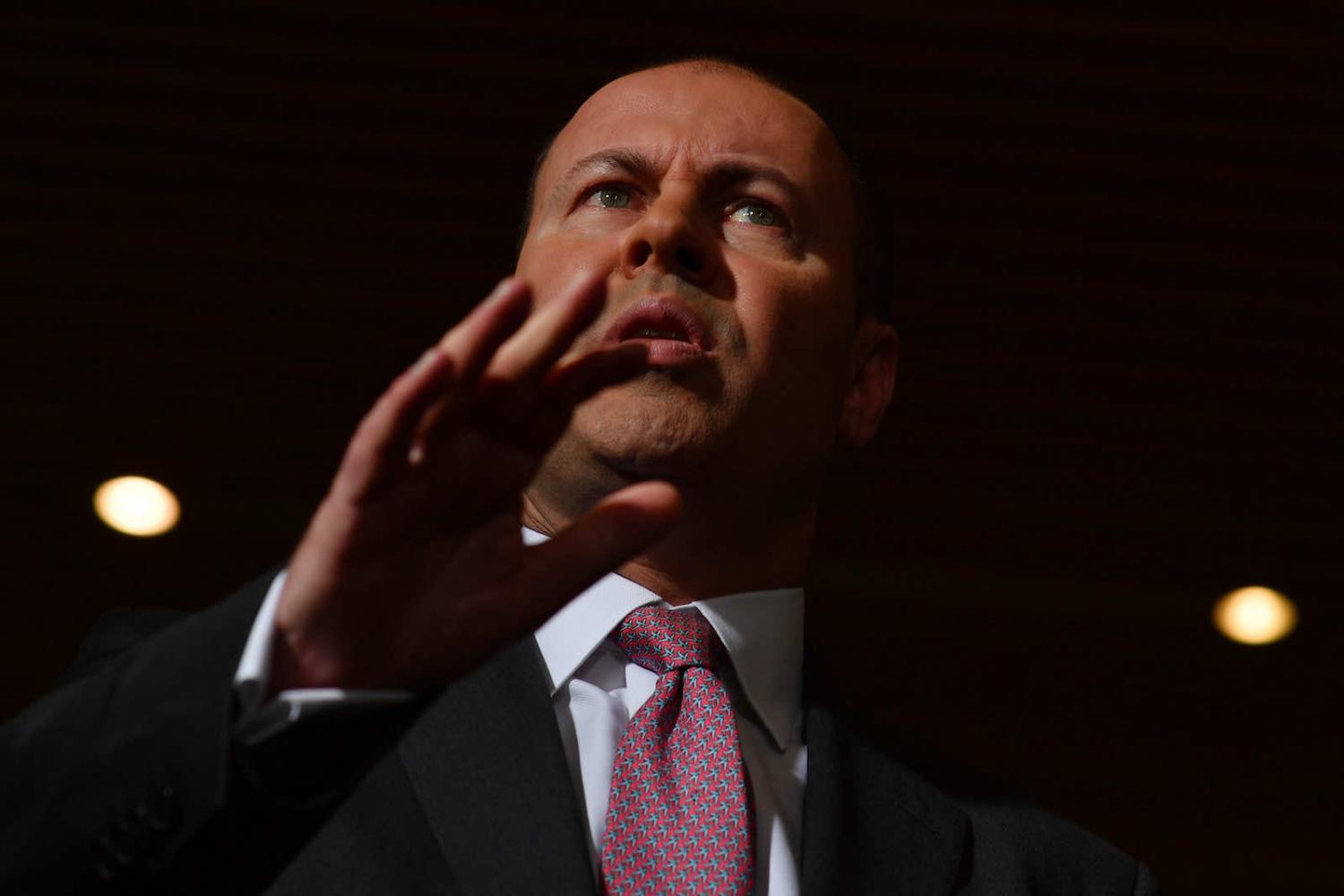

At the end of March last year, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg used the pandemic to usher in the biggest re-regulation of capital flows into Australia for decades.

And the emergency measures to “safeguard the national interest” against “predatory behaviour” by foreign investors morphed into the broader revamp of investment rules for national security reasons, which came into force this year.

In the latest Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) annual report, chairman David Irvine suggests Australia was just part of an international trend by suddenly requiring all potential foreign investment be subject to formal review.

But that rather downplays the way Frydenberg was really at the frontline of the global investment crackdown as the pandemic hit, despite coming from a country that depends on foreign capital and normally advocates open markets. And while the Treasurer denied the emergency measures were aimed at any one country, they nonetheless seemed to mark a new phase of muscling up in the economic relationship with China. As Frydenberg said at the time:

It’s about a situation that we find ourselves in with distressed companies that may be the target of buyers, of buyers whose behaviour is not in the national interest.

Now, thanks to commendable transparency from FIRB under Irvine’s more open leadership, we have some insight into what really happened in the fire sale of vulnerable Australian businesses. And we also have the first limited insight into the sort of investment which is no longer reported in the FIRB figures due to the way free trade deals over the past decade have removed the need for approval of many investments up to a threshold of $1.2 billion.

It will never be known whether the feared “predatory” investors were scared off by the new reporting requirements or whether they never actually posed much of a threat after all.

In the three months to the end of the financial year after the sudden crackdown there were 150 of the new zero threshold applications which would not have been picked up under the old system. And 137 of them valued at $2.7 billion were approved with less than a quarter having any conditions imposed. Most of the remainder were withdrawn.

This was miniscule compared with the normal recorded investment where there were 8084 approvals valued at $192.8 billion with 45% valued at $138 billion having conditions imposed. And in this case more than 700 were withdrawn, which can be a face-saving way of avoiding outright rejection.

It will never be known whether the feared “predatory” investors were scared off by the new reporting requirements or whether they never actually posed much of a threat after all.

But FIRB does cautiously warn that the zero threshold applications were piling up as the current financial year started and accounted for about 40% of the 535 applications then yet to be processed.

Follow the money

In the end the pandemic did not upset Australia’s attraction to overseas investors too much. Overall, normal non-zero-threshold approvals were down 7.3% and the value down 16.5%, although the full impact of the pandemic will perhaps be clearer this year.

And Irvine says the new permanent system which allows the Treasurer to exert a specific national security power over all foreign investment “will significantly enhance the administration of the framework and ensure Australia remains at the forefront of foreign investment policy and practice.”

Meanwhile, investment from China, the country that is seen as having largely triggered this re-regulation, remained quite stable with approved applications of $12.8 billion compared with $13.8 billion the previous year.

However, it dropped from fifth largest source country to sixth largest, and the amount is now half what it was only two years ago, underlining the cooling relationship.

The value of proposed investment from China in agriculture, forestry and fishing sector, finance and insurance sector, manufacturing, electricity and gas sector and the real estate sector increased. There was a decrease in the value of approvals in the mining services.

The US, Japan, Singapore, Canada and the United Kingdom now all top China. However, the rapid assertion of Chinese control over Hong Kong creates a dilemma, because if the two are aggregated they would still be in second position after the United States.

Nevertheless, as noted here and here previously using different data, Japan is the standout rising foreign investor in Australia with approval for $22 billion last year which is up from less than $5 billion only two years ago.

This deepening of an old bilateral alignment across both security and business driven by a diversified Japanese investment boom is an intriguing development when there is speculation about the need for a new submarine supplier.

Divining diversification

The relatively benign outcome on Chinese investment after the fear of opportunistic takeovers during the pandemic provides a timely foundation for the latest business community push-back against anti-China sentiment in Canberra.

The Business Council of Australia’s Living on Borrowed Time report on economic growth released this week uses quite anodyne language to call for a revival of economic engagement with the region.

But chief executive Jennifer Westacott didn’t hold back in an interview with The Australian newspaper saying the country would not achieve its desired economic or productivity growth goals from the new Intergenerational Report without a strong and ongoing trading relationship with China.

With the government beefing up resources across the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Austrade to give some substance to its diversification rhetoric, Westacott said the trade diversification agenda should not be seen as “diversification away from China – it’s diversification to other things”.

But as noted in the FIRB approvals above and here last month, while Chinese investment has remained stable into Australia, Westacott’s members and other businesses quietly slashed their cumulative stock of direct investment in China last year.

The problem for the Canberra security hawks and diversification doves alike is that those same businesses also reduced their stock of direct investment into the diversification targets of Japan, India and Southeast Asia.