An end-of-year series as the Lowy Institute staff and Interpreter contributors offer their favourite books, articles, films or TV programs this year. Look back on the series and watch for more recommendations and reflections in the days ahead.

Long before a certain New York real estate developer became president of the United States, political observers had a nagging question: why are so many Americans voting against their own interests?

Waves of so-called conservative politicians and activists gutted post-war American industry and strangled organised labour, while Wall Street and corporate boards were exalted to high holiness. Millions of Americans had big stakes but little say in how (or where) things should go.

In the shift to the financialising of everything, “shareholder value” became a sacred incantation rendering all other metrics secondary. As executive pay rose higher and higher (and taxes lower and lower), regular workers’ wages stayed flat as a pancake. “The Great Uncoupling” had begun.

And we can all see where it’s gone. A pandemic is killing 3000 Americans a day, at last count. But it’s just a political game. Universal healthcare? Dream on. Climate change? It’s debatable. QAnon? Absolutely.

How can this be? How do values get ripped out of a culture? What kind of country does this?

Kurt Andersen goes looking for the culprits in Evil Geniuses. And he finds a whole lot of them, a cast of familiar and not-so-familiar names who, for whatever else they may have intended, have turned America into a funhouse that for many is no fun at all.

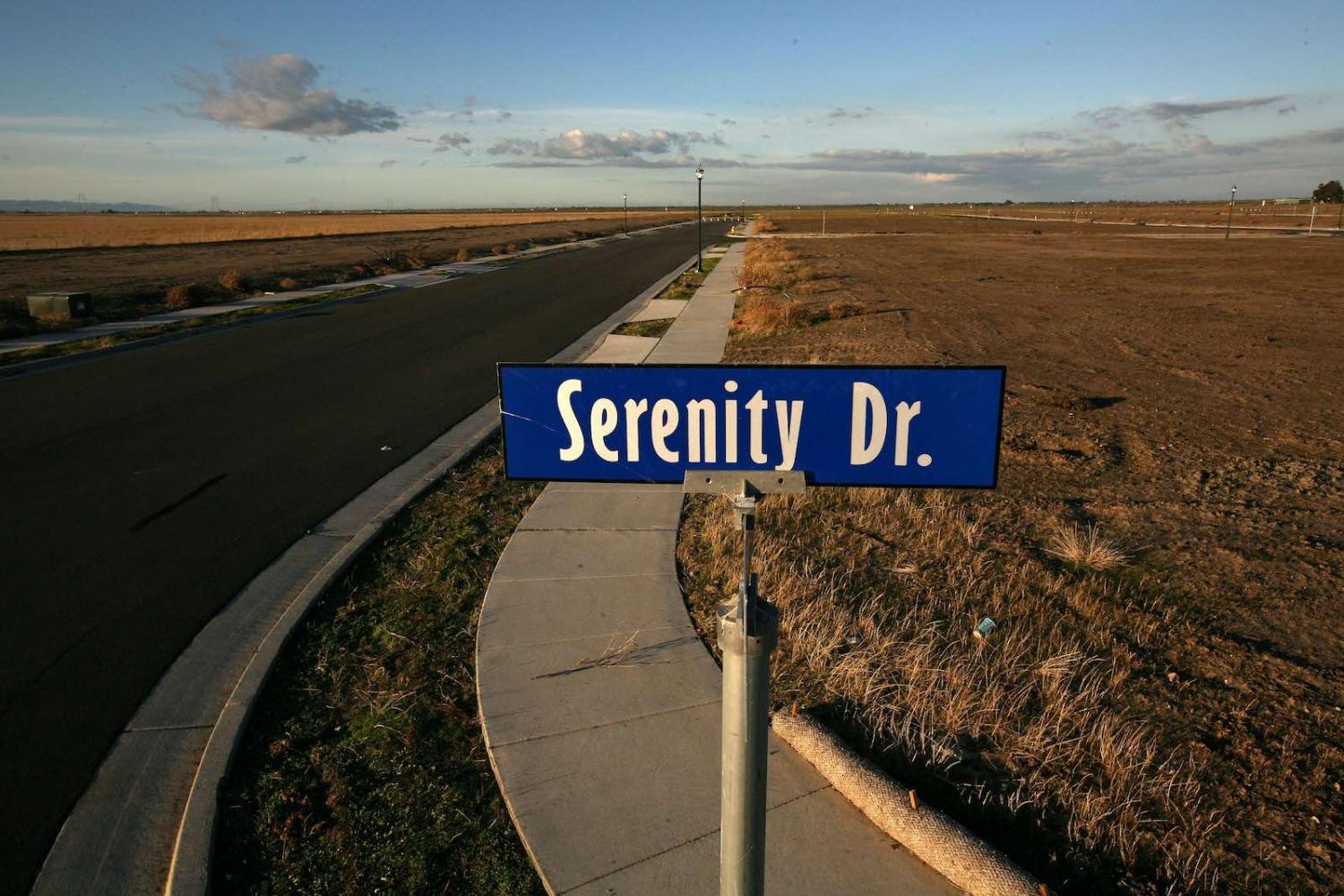

The coup de grace was getting the suckers who’d been stuck with the bill, whose jobs went elsewhere and whose towns were hollowed out, to keep voting for politicians who kept shovelling wealth into the pockets of the privileged few, and to enlist them in the cause. Because somebody else did this to you, not us.

This project took decades, a grinding campaign played out in think tanks and courtrooms and legislatures and speeches, but perhaps most egregiously in the media. You, too, can triumph in this dog-eat-dog world if only you believe: “Times are tough! Government can’t save you! Adapt or die!”

The driving force of this new America is greed.

In the evolving American social contract, the balance among the competing demands of liberty and equality and solidarity (or fraternité) worked pretty well for most of the 20th century, the arc bending toward justice. But then came the ultra-individualistic frenzy of the 1960s, and during the 1970s and 80s, liberty assumed its powerfully politicised form and eclipsed equality and solidarity among our aspirational values. “Greed is good” meant that selfishness lost its stigma. And that was when we were in trouble.

Andersen’s previous work, Fantasyland, dug to the roots of US history to examine how the country’s choose-your-own-reality mindset has been there from the get-go and has never gone away – the source of its greatest inventions and cruellest delusions.

Something of a sequel, Evil Geniuses brings deep research, stacks of data and decades of experience in big-name journalism to examine the long, slow but in many ways deliberate “unmaking of America”.

Others have looked at this terrain through the lens of economics, politics or culture. Andersen looks through all of them, pointing out the all-hat, no-cattle cowboys riding across the prairie.

In this view, Donald Trump, reality-TV huckster turned president, is not such an outlier after all. If anything, he implicitly adds a cunning corollary to the slightly more fictitious Gordon Gekko’s theory of greed: Yeah, but graft is better.

There is little joy in confronting this brutal history, but Andersen’s balance of earnest inquiry and acerbic wit keeps it snappy. And, in characteristic American fashion, he ends on an optimistic note. Most Americans, on paper at least, don’t want this status quo. We’ve been in similar circumstances, a century or more ago. There was a reckoning, followed by progress, and progress is possible again.

2021 can’t come soon enough.