The Turnbull government is spending $200 billion over the next decade to build-up our military capabilities, the largest amount in peacetime history. We need those weapons, vehicles, ships, systems, and aircraft to defend our nation and our interests.

Capability is our first priority but, unlike previous governments, we are looking to invest as much of that commitment here in Australia to drive jobs, wealth, and growth in our economy.

A strong defence industry in Australia gives us greater self-reliance. It allows us to do more in the region, and for our people to feel safer and more secure. Australia will never be completely self-reliant in terms of defence materiel, but that shouldn’t and won’t stop us from striving to be as self-sufficient as possible.

Each day I am given more reasons to be impressed with and encouraged by Australia’s defence industry. Our defence industry has the development capability, and that is the most important thing. However, we have been letting ourselves down by not capitalising enough on our global competitiveness and selling that capability to our friends and allies, as they sell to us.

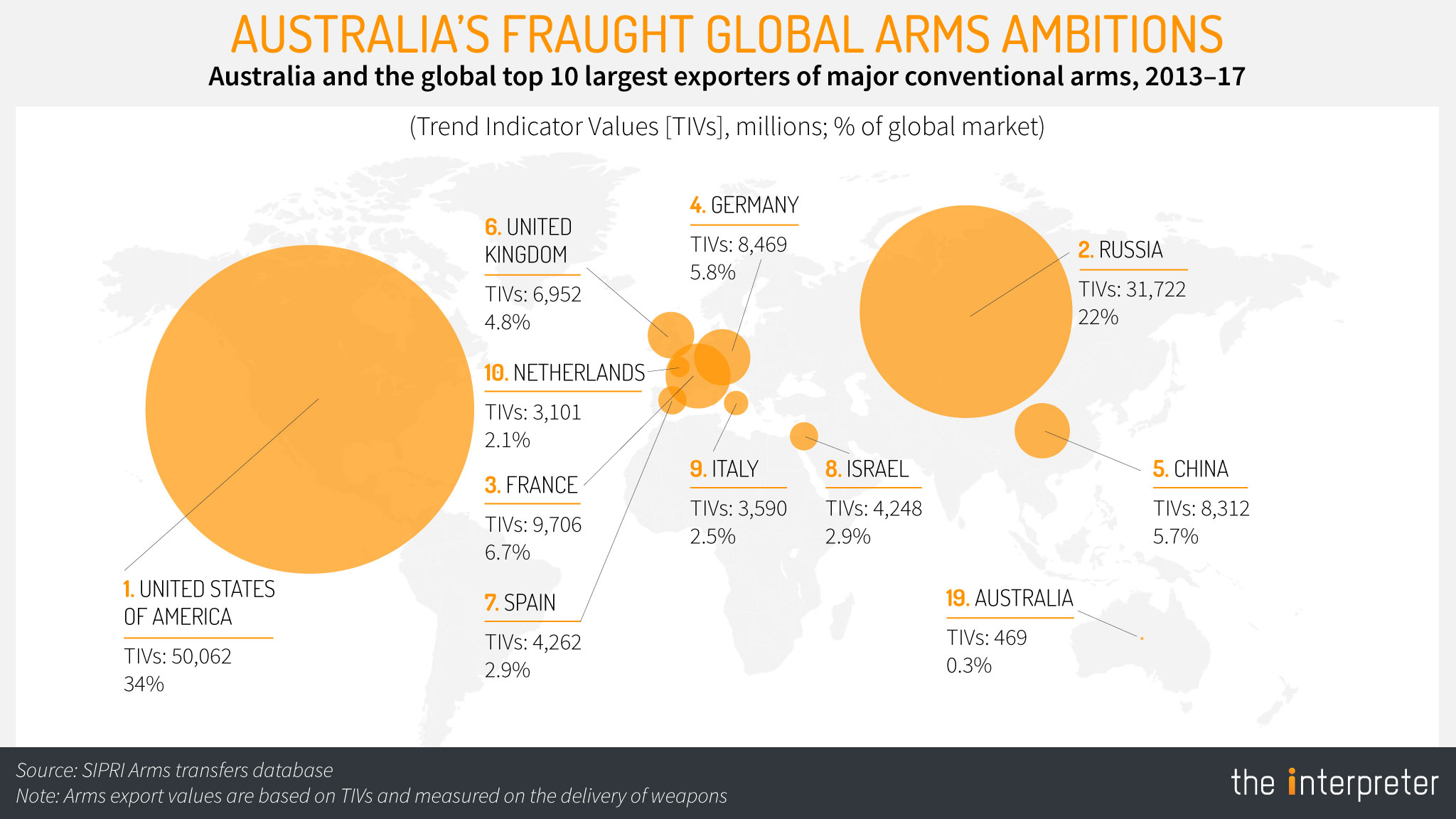

To better help Australia and our defence industry reach its full potential, the Prime Minister and I, along with the Minister for Defence, launched the Defence Export Strategy at the start of the year. The Strategy is the first of its kind and will bring together the efforts of the Government and industry as we aim to grow Australia’s defence industry, with an ambitious goal to become a top-ten global defence exporter within a decade.

As part of the Strategy, the Australian Government will establish a Defence Export Office which will be a first port of call for defence companies wanting to export, and be responsible for implementing the various programs and initiatives of the Strategy. I encourage Australian defence companies who are looking to export capabilities to seek them out.

I will also appoint an Australian Defence Export Advocate who will identify export markets and coordinate our campaign efforts. This person will help me by being at the right hand of industry as we seek to engage with the governments and militaries of our friends and allies and look to promote the export of our world-class materiel.

We are supporting Australian companies to reach overseas markets in other ways. Last week, I launched the second edition of the Australian Military Sales Catalogue which features the products and services available from 69 Australian businesses.

It’s worth examining why this Export Strategy is so vital.

Defence industry and defence exports are unique because their only customers are governments. When an Australian company goes overseas to try and sell to a government, the first question is always, “Does Australia support this?” That’s why I regularly speak to my counterparts in the governments of our friends and allies around the world to endorse and recommend Australian defence industry companies and equipment.

I often say that Australia will never be able to compete when it comes to making T-shirts. But we can compete when it comes to making high-end, world-beating defence equipment: from radars to armoured vehicles, ammunition to radios, sonars to tail fins, and yes, even warships.

Like any industry, a strong defence industry is one that exports. Our country as a whole benefits from exports. An exporting company is in a better position to expand more, employ more, and invest more in R & D. That allows Australia’s defence industry to deliver better capability to our forces, and to help them better defend our country.

It also provides a strong and growing career path for young Australians in the defence sector – not only in the Department of Defence and Defence Forces, but also in our defence industry. It’s exciting, it’s useful, and it helps defend our country. And, as Australian of the Year, Professor Michelle Simmons told me during a recent interview on my Sky News show Pyne & Marles, one of the challenges of attracting young Australians into STEM courses is to show them the types of jobs this path of study can lead to.

Australia is world-leading in the production of military equipment and components.

For example, the CEA Phased Array Radar is better than the radar used in the US, is being considered by the UK for use on some ships, is the most capable radar of its type in the world, and is standard on our new ships. It’s made in Fyshwick, an industrial suburb in Canberra.

The Bushmaster and Hawkei vehicles, made by Thales Australia in the regional town of Bendigo, are world-beating when it comes to troop protection and movement. Thales Australia also exports sonar products to France.

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) index recently upgraded Australia’s export ranking one place, to position 19. But SIPRI doesn’t include much of Australia’s production, and therefore seriously underestimates our overall output.

SIPRI only captures major platforms and subsystems, and only uses public-source data. Australia makes some major platforms, such as Bushmaster vehicles or Austal’s ships for the US Navy, but it makes a lot more components.

SIPRI doesn’t include Birdon, who won a US $261 million contract to make boats for the US Army. It doesn’t include the Nulka decoy, to a value of over $1 billion. It doesn’t include Thales’s $500 million of exported sonar technology. Nor does SIPRI include the more than $1 billion of exports of components for the Joint Strike Fighter.

We’re already further up that ranking than we think we are. But I want us to be higher.

The Turnbull government is transforming the way we acquire military capability, and defence companies from around the world have responded. They no longer just outline the strengths of the capability they can develop and manufacture. They also demonstrate how many Australian workers will be employed, how many Australian companies will be in the supply chain, how much Australian product will be used, and how Australian industry will be further developed.

For example, with the recent announcement of the decision to build 211 Rheinmetall Boxer armoured fighting vehicles, it was shown that Australian industry content for the acquisition and sustainment of the vehicles would be around 70%; up to 1450 jobs will be created nationally; more than 40 local suppliers would be used from around the country; and that Rheinmetall would establish a Military Vehicle Centre of Excellence.

We are seeing similar commitments from the three companies who submitted tenders to build our future frigates.

More than 10,000 direct new jobs, and tens of thousands more indirectly, will be created by companies investing in Australia and our defence industry based on the certainty given by the Government’s clear commitment and direction. Our nation will be more secure because of that clear commitment and direction. Our Defence Export Strategy not only complements, but is a logical extension of our significant $200 billion investment in military capability.