Street art has been much discussed across Indonesia’s airwaves in the last couple of months. Three spray-painted murals expressing a critical perspective on the government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic were quickly covered over by officials, igniting heated debates about free expression and the role of street art in national politics harking back to the country’s independence struggle.

Although the graffiti controversy has dimmed slightly in recent weeks, the debate could soon surge again with the potential for a third wave of the pandemic in Indonesia – with the country already an epicentre for the virus and one of the biggest contributors of daily cases globally.

The murals appeared in the context of complaints about official responses to Covid-19, with many of the problems in the health sector still to be addressed. The most controversial street art was painted in a tunnel on the outskirts of Jakarta, depicting a figure that resembled President Joko Widodo with his eyes covered and captioned “404: Not found”. Evidently a reference to the internet standard “404” error when a hyperlink is broken, the image has become a symbol for many in Indonesia disenchanted with the government, while the phrase “404: Not found” has turned into a rallying cry for freedom of expression. The street art ruffled the feathers of authorities, who claimed it insulted the President as “a state symbol”, leading police to search for the unknown creators.

Two other murals fed the polemic. Graffiti with the words “Tuhan Aku Lapar” (God, I’m Hungry) and “Dipaksa Sehat di Negara Yang Sakit” (Forced to be Healthy in a Sick Country) were also later censored.

Murals feature in Indonesia’s political tradition stretching back to the pre-independence era in 1945.

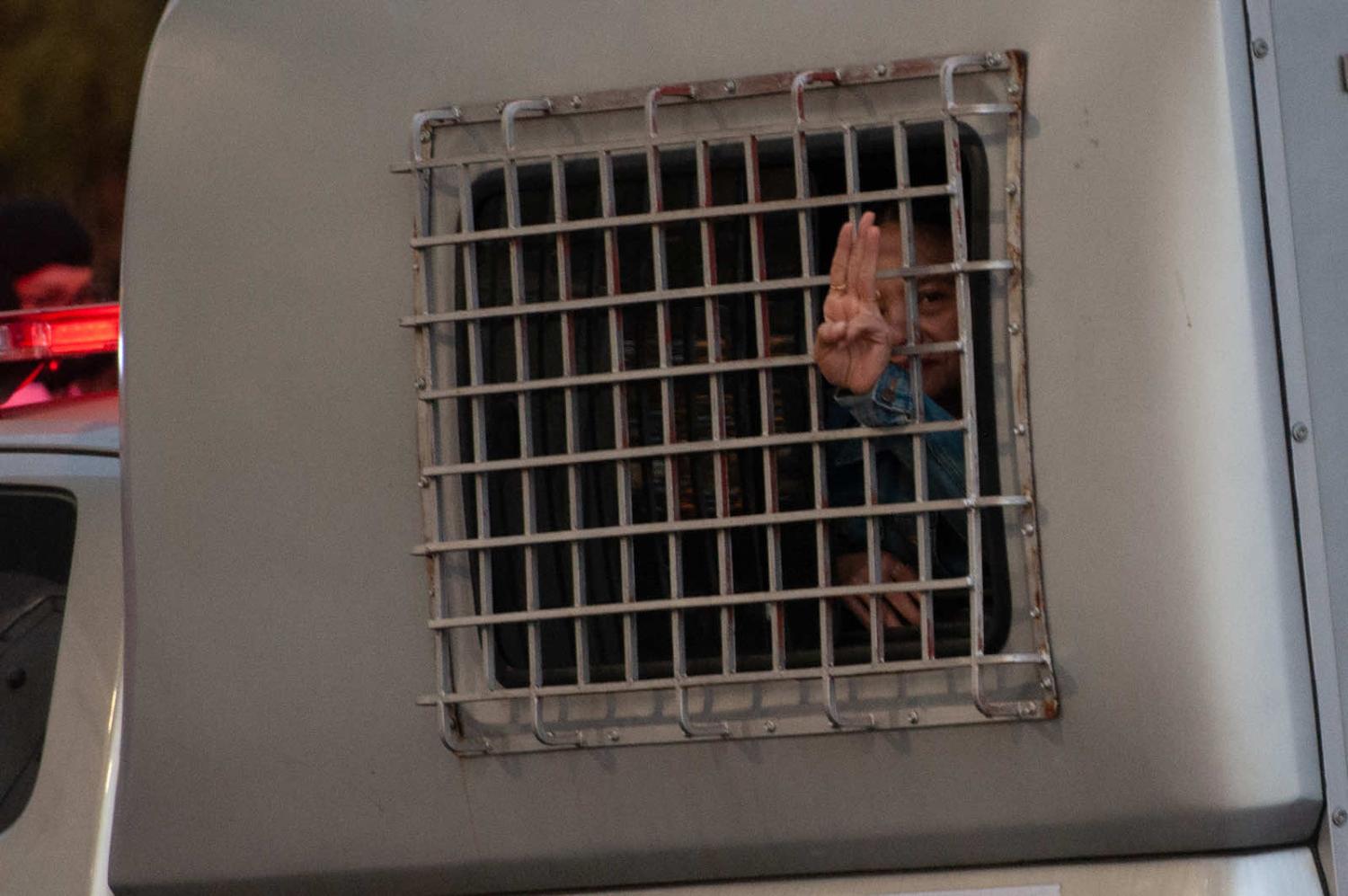

The administration is seemingly sensitive to the shortcomings in its handling of the Covid-19 crisis, which has been widely criticised as inadequate. But the crackdown has only drawn more attention to it. The chasing down of street artists has prompted the university students alliance Gejayan Memanggil in the city of Yogyakarta to call for mural contests, giving rise to aspiring Indonesian Banksys.

“This should be seen as policy feedback for government,” Adinda Tenriangke Muchtar, Executive Director for Jakarta-based think tank The Indonesian Institute, told me in an interview. “When we talk about democracy and abiding by the law, we need to question whether there is discrimination in society that incites this kind of expression – simply because people don’t have avenues to be heard or [responses to] their aspirations are tone deaf when submitted through formal political channels.”

The feedback reached the top. In his State of Union address in August, Jokowi, as the President is widely known, said he was aware that the government had received criticism for failing to resolve a number of problems. He thanked the people for their feedback and called them to continue to build a “democratic culture”.

Police subsequently announced that they would no longer pursue the creators of the “404: Not Found” mural, describing it as a “work of art”. Instead, they announced a mural contest with a Chief-of-Police Cup as a trophy. But observers saw this move as far too late. The threat of criminal charges had already been made and the desired “chilling effect” already achieved. Citizens will undoubtedly be much more hesitant about similar public expressions of criticism in the future. But then again, the writing has long been on the wall in Indonesian politics.

Murals feature in Indonesia’s political tradition stretching back to the pre-independence era in 1945. The most iconic example was the phrase “Freedom is the Glory of any Nation. Indonesia for Indonesians!” captured by Dutch photographer Cas Oorthuys. Historian JJ Rizal explained that the mural became an outlet for people in the newly-born nation to despise colonialism. The kind of work that Oorthuys’ camera recorded has long been both a means of mass communication and a valuable propaganda tool.

Other murals in West Java shot by photographer J. C. Taillie in 1947, such as “Terus Berjuang oentoek Keselamatan Bersama” (Keep Fighting for Our Safety), depicted pro-independence spirit, whereas graffiti scrawled on the wall of a house in West Java that same year called for “Full Independence and International Brotherhood of All Freedomloving Peoples”.

Indonesia’s street arts became a distinct subculture in the New Order era under Suharto, where a group of artists in Yogyakarta called Taring Padi created several murals as avenues to give voice to public critics. After Reformasi in the late 1990s, street art flourished in the country, with Respecta Street Art Gallery (RSAG) establishing Indonesian Street Art Database, a network of independently managed, community-based efforts towards a more comprehensive historical archive of murals, accessible not only to passers-by, but also to the public at large.

There seems no doubt that murals will continue to play a crucial role in Indonesia’s political discussions.