Fiji’s capital Suva has been in and out of Covid lockdowns over recent weeks, and my Netflix got a workout. I watched a TV show called “Cooked with Cannabis”. Admittedly there were a few baked hippies, but the cooking was good. Jokes aside, the show revealed the sophisticated and lucrative global cannabis industry, projected to grow to an extraordinary US$90.4 billion internationally by 2026.

Watching the show also got me thinking about Fiji’s economy as the country fights through a second wave of the pandemic via containment measures and a vaccination drive. Fiji has taken an almighty hit. GDP was slashed to approximately $4.3 billion in 2020, with growth falling by 19%, according to the International Monetary Fund. Foreign tourists have vanished, all non-essential businesses have been forced to close, and the much mooted Pacific travel bubble is likely to be off the cards for the immediate future. With national debt levels soaring, a nasty storm is brewing.

Fiji needs to diversify its economy away from a reliance on tourism. Despite the government’s best efforts to provide relief through food ration deliveries and a $90 emergency payment to families affected by Covid, these well-intentioned initiatives have arguably fallen short. Many people complained that calls to the food-ration hotline went unanswered, or the deliveries never arrived, while the need for Fijians to provide tax details in order to claim the relief payments meant those in the informal sector were all but left behind.

That’s where cannabis presents an opportunity.

A cannabis industry in Fiji would not be limited to growing the crop. A whole value-add supply chain could be created.

Currently marijuana or saba (pronounced “samba”, yes, like the dance) is illegal in Fiji. But of course the leaf is grown. One of my favourite news pieces from 2020 was about villagers shooting down police drones with spear guns to hide their marijuana plantations on Kadavu, an island south of Suva. The police still managed to haul in crops said to have a street value of FJ$86 million (A$50 million) in a four-week operation and amount to the largest seizure ever in the country.

But it seems ironic that at a time when some families can’t afford to put food on the table, millions of dollars worth of this currently illegal crop would be uprooted.

The over-reliance on tourism, comprising almost 40% of Fiji’s GDP before the pandemic has left economic void. Rebooting the agricultural sector is an area the Fijian government has identified as one which could be strengthened. Fiji has a solid history of agricultural exports. In the 1970s sugar exports accounted for 70% of the country’s export earnings. More recently, yaqona (kava) has been targeted as a growth opportunity in the sector, due to its widespread use in the region for relaxation and stress relief. Unfortunately, yaqona takes several years before it can be harvested. Like other agricultural products, it is also exposed to heightened risks of environmental damage, for example cyclones.

But “weed” is different. As the name suggests, cannabis is a resilient crop and capable of harvesting after three months. As the “spear gun incident” attests, it clearly grows well in Fiji.

With an ideal climate, remote islands capable of quarantining cannabis operations, a world renowned “brand Fiji” offers a special opportunity for economic diversification. Just look at Fiji Water.

The idea of a marijuana industry in Fiji is not new. The idea was debated most recently in March at a Nadi Chamber of Commerce roundtable. The government was adamant in response it has no plans to legalise marijuana.

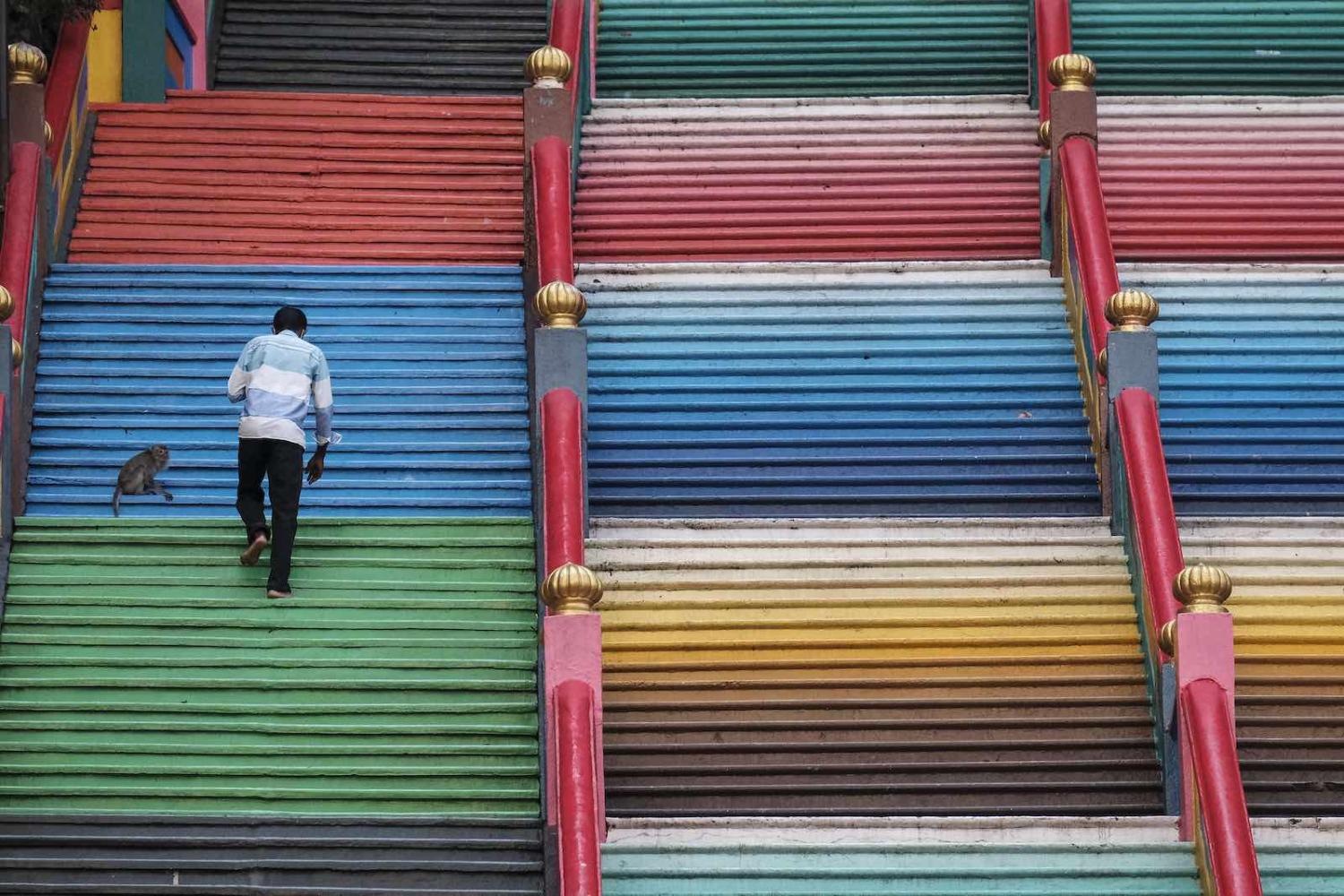

But “legalisation” need not mean we all get “cooked with cannabis”. Fiji could do what other countries have done, legalising marijuana for medicinal and hemp fibre production, while banning recreational use. Such a move would follow similar regulation in countries including Malawi, Lesotho and Uganda, as well as Thailand in Southeast Asia, among others.

A permit system could be created for growing marijuana on designated islands in Fiji. Alternatively, the government could create a stated owned company to manage production – afterall if there is a Fiji Sugar Corporation, why not a Fiji Cannabis Co.?

A cannabis industry in Fiji would not be limited to growing the crop. A whole value-add supply chain could be created, for example, through hemp fibre production (Fiji’s garment manufacturing industry has also felt the pinch under Covid), as well as labs to extract the valuable CBD oil, which is used for pain relief and various other ailments. This could all be carried out in Fiji and create jobs for Fijians.

There will be concern about any partial legalisation leading to greater recreational use of cannabis among the local population. It cannot be ruled out, but the same “slippery slope” argument can also apply to tobacco and alcohol as gateways to substance abuse. Those partial to the saba are still likely to partake, whether it is legal or not. These are the types of risks the government should be able to manage with responsible regulation and enforcement.

From a business perspective, there is a chance for Fiji to be the region’s “first mover” in the cannabis industry. Research and a feasibility study should be first undertaken to determine the viability and opportunity that a cannabis industry could present. From there, a better judgement can be made about what would be required to regulate it.

And just maybe the volatility of the pandemic could be the catalyst for Fiji to innovatively diversify the economy and generate a new export market to its advantage.